Autistic ways of being are human neurological variants that can not be understood without the social model of disability.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

If you are wondering whether you are Autistic, spend time amongst Autistic people, online and offline. If you notice you relate to these people much better than to others, if they make you feel safe, and if they understand you, you have arrived.

We’re autistic. You probably believe some wrong things about us. Myths, misconceptions, and misguided awareness campaigns overwhelm and erase the actual lived experiences of autistic people. Here is what we’d like you to know about us, autism, and our needs.

Table of Contents

- What is Autism?

- What Are Autistic Ways of Being?

- Autistic Traits

- The Spectrum

- Autism, Society, and Me

- Am I Autistic?

- What’s Next After Diagnosis/Self-Identification?

- Community Resources

- Respectfully Connected: Advice to Teachers and Parents of Autistic Kids

- How to Create an Autism Inclusive Environment

- Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

- Find Your People and Co-Create Ecologies of Care

What is Autism?

In the absence of a comprehensive neurological and genetic description – which may forever remain elusive, the best way to describe Autistic ways of being is in terms of first hand lived experience of Autistic cognition and Autistic motivations.

The following definition of Autistic ways of being reflects a collective effort of the Autistic community. Focusing on common first hand experiences leads to a relatively compact description that can easily be validated by Autistic readers, and it also avoids getting lost in endless lists of externally observable behaviours. Lists of external diagnostic criteria offer very little insight into underlying Autistic sensory experiences and Autistic motivations.

Instead of a diagnosis, the following test tends to deliver very reliable results. It does not cost any money, it only takes some time. For anyone who relates to the communal description of Autistic ways of being below, this investment of time may be the most valuable investment imaginable:

If you are wondering whether you are Autistic, spend time amongst Autistic people, online and offline. If you notice you relate to these people much better than to others, if they make you feel safe, and if they understand you, you have arrived.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Autism is a developmental phenomenon, meaning that it begins in utero and has a pervasive influence on development, on multiple levels, throughout the lifespan. Autism produces distinctive, atypical ways of thinking, moving, interaction, and sensory and cognitive processing. One analogy that has often been made is that autistic individuals have a different neurological “operating system” than non-autistic individuals.

WHAT IS AUTISM? • NEUROQUEER

Autism is still widely regarded as a “disorder,” but this view has been challenged in recent years by proponents of the neurodiversity model, which holds that autism and other neurocognitive variants are simply part of the natural spectrum of human biodiversity, like variations in ethnicity or sexual orientation (which have also been pathologized in the past). Ultimately, to describe autism as a disorder represents a value judgment rather than a scientific fact.

WHAT IS AUTISM? • NEUROQUEER

Autism is a developmental disability that affects how we experience the world around us. Autistic people are an important part of the world. Autism is a normal part of life, and makes us who we are.

Autism has always existed. Autistic people are born autistic and we will be autistic our whole lives. Autism can be diagnosed by a doctor, but you can be autistic even if you don’t have a formal diagnosis. Because of myths about autism, it can be harder for autistic adults, autistic girls, and autistic people of color to get a diagnosis. But anyone can be autistic, regardless of race, gender, or age.

Autistic people are in every community, and we always have been. Autistic people are people of color. Autistic people are immigrants. Autistic people are a part of every religion, every income level, and every age group. Autistic people are women. Autistic people are queer, and autistic people are trans. Autistic people are often many of these things at once. The communities we are a part of and the ways we are treated shape what autism is like for us.

There is no one way to be autistic. Some autistic people can speak, and some autistic people need to communicate in other ways. Some autistic people also have intellectual disabilities, and some autistic people don’t. Some autistic people need a lot of help in their day-to-day lives, and some autistic people only need a little help. All of these people are autistic, because there is no right or wrong way to be autistic. All of us experience autism differently, but we all contribute to the world in meaningful ways. We all deserve understanding and acceptance.

About Autism – Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

Autistic people have differences in the development of their anterior cingulate cortex, a part of the brain that helps regulate attention, decision making, impulse control, and emotional processing. Throughout our brains, Autistic people have delayed and reduced development of Von Economo neurons (or VENs), brain cells that help with rapid, intuitive processing of complex situations. Similarly, Autistic brains differ from allistic brains in how excitable our neurons are. To put it in very simple terms, our neurons activate easily, and don’t discriminate as readily between a “nuisance variable” that our brains might wish to ignore (for example, a dripping faucet in another room) and a crucial piece of data that deserves a ton of our attention (for example, a loved one beginning to quietly cry in the other room). This means we can both be easily distracted by a small stimulus and miss a large meaningful one.

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

What Are Autistic Ways of Being?

Autistic people / Autists must take ownership of the label in the same way that other minorities describe their experience and define their identity. Pathologisation of Autistic ways of being is a social power game that removes agency from Autistic people. Our suicide and mental health statistics are the result of discrimination and not a “feature” of being Autistic.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Autistic inertia is similar to Newton’s inertia, in that not only do Autistic people have difficulty starting things, but they also have difficulty in stopping things. Inertia can allow Autists to hyperfocus for long periods of time, but it also manifests as a feeling of paralysis and a severe loss of energy when needing to switch from one task to the next.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

“I am not the math-minded type of Autistic,” Tisa says. “I am the kind who thinks about people obsessively.

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

Every autistic person experiences autism differently, but there are some things that many of us have in common.

- We think differently. We may have very strong interests in things other people don’t understand or seem to care about. We might be great problem-solvers, or pay close attention to detail. It might take us longer to think about things. We might have trouble with executive functioning, like figuring out how to start and finish a task, moving on to a new task, or making decisions.

Routines are important for many autistic people. It can be hard for us to deal with surprises or unexpected changes. When we get overwhelmed, we might not be able to process our thoughts, feelings, and surroundings, which can make us lose control of our body.- We process our senses differently. We might be extra sensitive to things like bright lights or loud sounds. We might have trouble understanding what we hear or what our senses tell us. We might not notice if we are in pain or hungry. We might do the same movement over and over again. This is called “stimming,” and it helps us regulate our senses. For example, we might rock back and forth, play with our hands, or hum.

- We move differently. We might have trouble with fine motor skills or coordination. It can feel like our minds and bodies are disconnected. It can be hard for us to start or stop moving. Speech can be extra hard because it requires a lot of coordination. We might not be able to control how loud our voices are, or we might not be able to speak at all–even though we can understand what other people say.

- We communicate differently. We might talk using echolalia (repeating things we have heard before), or by scripting out what we want to say. Some autistic people use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) to communicate. For example, we may communicate by typing on a computer, spelling on a letter board, or pointing to pictures on an iPad. Some people may also communicate with behavior or the way we act. Not every autistic person can talk, but we all have important things to say.

- We socialize differently. Some of us might not understand or follow social rules that non-autistic people made up. We might be more direct than other people. Eye contact might make us uncomfortable. We might have a hard time controlling our body language or facial expressions, which can confuse non-autistic people or make it hard to socialize.

Some of us might not be able to guess how people feel. This doesn’t mean we don’t care how people feel! We just need people to tell us how they feel so we don’t have to guess. Some autistic people are extra sensitive to other people’s feelings.- We might need help with daily living. It can take a lot of energy to live in a society built for non-autistic people. We may not have the energy to do some things in our daily lives. Or, parts of being autistic can make doing those things too hard. We may need help with things like cooking, doing our jobs, or going out. We might be able to do things on our own sometimes, but need help other times. We might need to take more breaks so we can recover our energy.

Not every autistic person will relate to all of these things. There are lots of different ways to be autistic. That is okay!

About Autism – Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Autistic people process the world from the bottom up.

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

What unites us, generally speaking, is a bottom-up processing style that impacts every aspect of our lives and how we move through the world, and the myriad practical and social challenges that come with being different.

Autistic Traits

If you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person.

Community Saying Emphasizing That We are Individuals

Autism: The Positives

An interesting discussion in our program lately where I’ve argued against lumping autistic traits into “challenges” & “benefits” as most can be both/either/neither. Rather we should support the person so traits can be felt as benefits more often. Great graphic (@UniversityLeeds)

John Marble on X

Keeping in mind that we’re all individuals with individual expressions of our spiky profiles, here are some introductory pages on common autistic traits and experiences.

- Spiky Profile

- Alexithymia

- Asynchronous Communication

- Autistic Language Hypothesis

- Autistic Rapport

- Burnout

- Canary

- Dandelions, Tulips, and Orchids

- Demand Avoidance

- Dolphining

- Echolalia

- Executive Function

- Exposure Anxiety

- Eye Contact

- Fawn

- Fidgeting

- Food Aversion

- Gestalt Learning

- Hyperlexia

- Interoception

- Justice Sensitivity

- Meerkat Mode

- Meltdown

- Monotropic Spiral

- Monotropic Split

- Monotropism

- Neuroception

- Neuroqueer

- Neurospicy

- Noncompliance

- Nonspeaking

- Phone Calls

- Play

- Problem Behavior

- Processing Time

- Queer

- Rabbit Hole

- Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

- Rumination

- Samefood

- Self-Injurious Stimming

- Sensory Hell

- Sensory Trauma

- Situational Mutism

- Sleep

- Sparkle Brain

- Special Interest

- SpInfodump

- Stim Listening

- Stimming

- Stim-Watching

- Support Swapping

- Very Grand Emotions

- Weird

- Neuroception and Sensory Load: Our Complex Sensory Experiences

- Perceptual Worlds and Sensory Trauma

- The Five Neurodivergent Love Locutions

The Spectrum

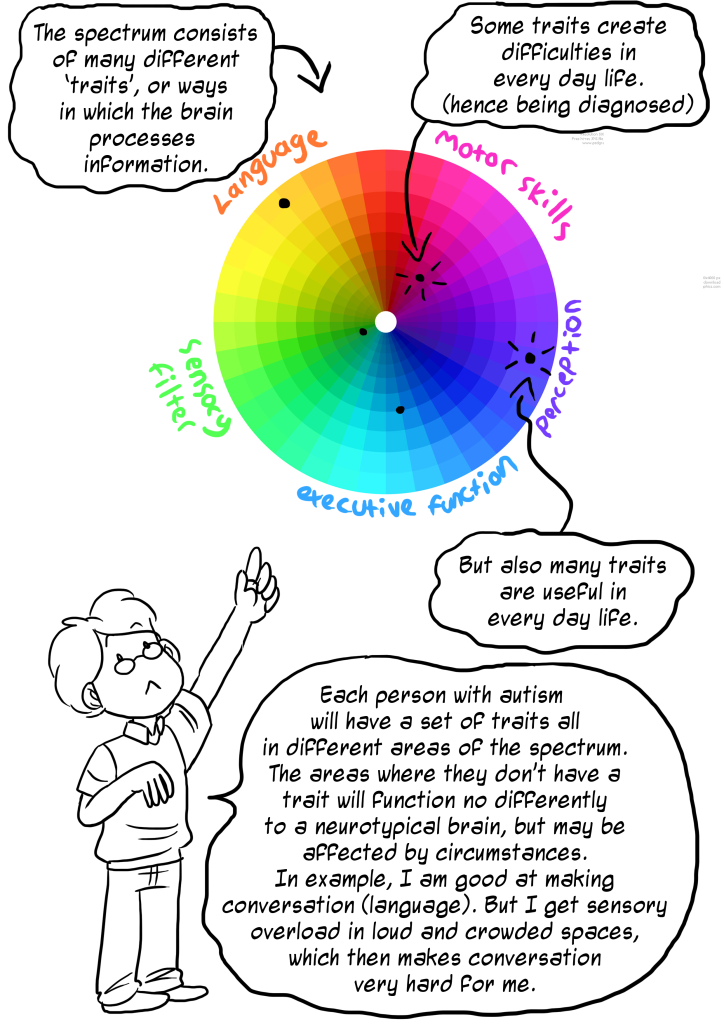

“Understanding the Spectrum” by Rebecca Burgess is a popular re-conceptualization of the autism spectrum from a line to a color wheel. A color wheel better captures our spiky profiles. Thank you, Rebecca, for giving this to the world.

If you are looking to contact me about my “Understanding The Spectrum” comic, please find a print-quality PDF of the comic at this link here. No need to email me to ask for permission to use it, I have always intended for the comic to be completely free to use in whatever you like, be it in presentations or for translating. When you do use it though, please credit me for the image and let me know that you’ve used it, because I love to know that this old comic is still doing much good in the world!

contact | rebecca-burgess

Autism, Society, and Me

This list is presented as first person but compiled from the perspectives of several autistic Stimpunks.

- I have difficulty responding to greetings and compliments. I am not rude; it’s just hard. Please afford me space and understanding, and recognize that sociality has many ways of expression.

- Auditory processing and time perception differences mean I need extra processing time during social and learning interactions. Be patient, and don’t get frustrated or insulted if I can’t respond.

- Sensory overwhelm is a marquee feature of my life. Autistic perception can be a high fidelity flood in an intense world. “Autistic perception is the direct perception of the forming of experience. This has effects: activities which require parsing (crossing the street, finding the path in the forest) can be much more difficult. But there is no question that autistic perception experiences richness in a way the more neurotypically inclined perception rarely does.”

- Anxiety is common among autistic people, including myself

- “Autistic anxiety is a powerful presence in my life. Its intensity can be unfathomable to a neurotypical mind.”

- “While anxiety disorder exists by itself, if autism is the dx, anxiety is a bi-product. It’s because Autistic individuals take sooooooo much in. Especially in early childhood, until they gain experience & make sense of their world, the anxiety can be overwhelming.“

- Sometimes I need a mind/body break. I need to be alone, I need to be in my head, and I need to stim.

- I stim by flapping my arms and clapping my hands while pacing.

- Stimming is a necessary part of sensory regulation. Stimming helps keep me below meltdown threshold.

- “Stimming is a natural behavior that can improve emotional regulation and prevent meltdowns in stressful situations.“

- “Let them stim! Some parents want help extinguishing their child’s self-stimulatory behaviors, whether it’s hand-flapping, toe-walking, or any number of other “stimmy” things autistic kids do.

- Most of this concern comes from a fear of social stigma. Self-stimulatory behaviors, however, are soothing, relaxing, and even joy-inducing.

- They help kids cope during times of stress or uncertainty.

- You can help your kids by encouraging parents to understand what these behaviors are and how they help.“

- Please proceed with what you are doing when I take a sensory break. I will observe from the edges and rejoin you when I am able.

- Autistic communities have a saying along the lines of, “I can either look like I’m paying attention, or I can actually pay attention.”

- Not making eye contact does not mean I’m not paying attention.

- “It may look like I am playing with something in my hands while my gaze is someplace far away, but I’m here with you – working to process things in my own way.”

- Please, never force eye contact. It is counter-productive, at best, and can cause physical pain.

- Embrace the obsession.

- Special interests are “intimately tied to the well-being of people on the spectrum“.

- “Special interests have a positive impact on autistic adults and are associated with higher subjective well-being and satisfaction across specific life domains including social contact and leisure.“

- “In my study, I found that when the autistic children were able to access their intense interests, this brought, on the whole, a range of inclusionary advantages. Research has also shown longer-term benefits too, such as developing expertise, positive career choices and opportunities for personal growth. This underscores how important it is that the education of autistic children is not driven by a sense of their deficits, but by an understanding of their interests and strengths. And that rather than dismissing their interests as ‘obsessive’, we ought to value their perseverance and concentration, qualities we usually admire.“

- “…the autistic children in my study were turning to their strong interests in times of stress or anxiety. And there has certainly been a lot of research which shows that autistic children and young people find school very stressful. So it might be the case that when this autistic trait is manifested negatively in school, it is a direct result of the stresses that school creates in the first instance.“

- “[E]nabling autistic children to engage with their strong interests has been found to be predominantly advantageous, rather than deleterious, in school environments.“

- “Furthermore, longer-term benefits have been associated with the pursuit of intense interests, with relatively few negative effects overall, which in themselves might only occur if autistic people are pressured to reduce or adapt their interests.“

- “Having intense or “special” interests and a tendency to focus in depth to the exclusion of other inputs, is associated with autistic cognition, sometimes framed as “monotropism”. Despite some drawbacks and negative associations with unwanted repetition, this disposition is linked to a range of educational and longer-term benefits for autistic children.“

- “Though they come with challenges, enthusiasms often represent the greatest potential for people with autism. What begins as a strong interest or passion can become a way to connect with others with similar interests, a lifelong hobby, or, in many cases, a career.“

- Prolonged sensory overwhelm can lead to meltdown.

- A meltdown is not a tantrum. It is not attention-seeking. It is a response to overwhelm, anxiety, and stress.

- If I meltdown, the best thing you can do is be present, patient, calm, quiet, and compassionate.

- Meltdowns are tidal waves of sensory overwhelm. Try not to add to the overwhelm.

- “But I’m tortured because whilst I don’t want to make a scene or have strangers adding to the overload and overwhelm, I’m simultaneously desperate for someone to give me a massive, firm, bear-hug. To hide me, cocoon me, and shield me from the shock waves that travel from their universe into mine.“

- Overwhelm, meltdowns, and the stress of trying to fit into neurotypical society lead to autistic burnout.

- “Burnout can happen to anyone at any age, because of the expectation to look neurotypical, to not stim, to be as non-autistic as possible. Being something that neurologically you are not is exhausting.”

- “If you saw someone going through Autistic Burnout would you be able to recognise it? Would you even know what it means? Would you know what it meant for yourself if you are an Autistic person? The sad truth is that so many Autistic people, children and adults, go through this with zero comprehension of what is happening to them and with zero support from their friends and families. If you’re a parent reading this, I can confidently say that I bet that no Professional, from diagnosis, through any support services you’re lucky enough to have been given, will have mentioned Autistic Burnout or explained what it is. If you’re an Autistic person, nobody will have told you about it either, unless you’ve engaged with the Autistic community. Autistic Burnout is an integral part of the life of an Autistic person that affects us pretty much from the moment we’re born to the day we die, yet nobody, apart from Autistic people really seem to know about it…“

- Our community uses identity-first language.

- I am an “autistic person”, not a “person with autism”, and certainly not a person “suffering from autism”.

- IFL is common in self-advocacy movements and preferred by neurodiversity and social model of disability communities.

- Whether someone uses IFL or PFL (person-first language), respect their preference.

- “When you excise a core defining feature of a person’s identity from their living, breathing self, you sort of objectify them a bit. And you make that core defining feature optional. Because it can be safely removed, and they’re still a person. Right? Well, a person, yes — but not the sort of person they know themselves to be. And not the sort of person you can truly get to know. Because you’ve denied one of the main characteristics of their nature, out of an intention to be … compassionate? Dunno. Or maybe sensitive? Whatever the original intention, the effect is just a bit dehumanizing. And a lot of us don’t like it.“

- Autistic people do not categorically lack empathy. In fact, many of us are hyper-empathic. Don’t mistake communication differences for lack of empathy. “One of the cruel ironies of autistic life is that autistic folks are likely to be hyper-empathic. Another irony is that neurotypicals and NT society are really, really bad at empathy and reciprocity. When your neurotype is the default, you have little motivation to grow critical capacity. Marginalization develops critical distance and empathic imagination.”

- The non-reflective embrace of “theory of mind” is itself a kind of “mind blindness”. It’s an empathic liability that gets in the way of understanding autistic and neurodivergent people.

- “And this is where the neurotypical belief in theory of mind becomes a liability. Not just a liability – a disability. Because not only are neurotypicals just as mind-blind to autistics as autistics are to neurotypicals, this self-centered belief in theory of mind makes it impossible to mutually negotiate an understanding of how perceptions might differ among individuals in order to arrive at a pragmatic representation that accounts for significant differences in the experiences of various individuals. It bars any discussion of opening up a space for autistics to participate in social communication by clarifying and mapping the ways in which their perceptions differ. Rather than recognize that the success rate of the neurotypical divining rod is based on mere statistical likelihood that the thoughts and feelings of neurotypicals will correlate, they declare it an ineffable gift, and use it to valorize their own abilities and pathologize those of autistics. A belief in theory of mind makes it unnecessary for neurotypicals to engage in real perspective-taking, since they are able, instead, to fall back on projection. Differences that they discover in autistic thinking are dismissed as pathology, not as a failure in the neurotypical’s supposed skill in theory of mind or perspective-taking.”

- Autism is not a disease. There is no cure for autism, nor do autistic people want to be cured. Autism is an integral part of our being. Removing it would be a death of self. Autistic is an identity, a community, and a culture. It is a valuable and natural part of human diversity.

- We are not puzzle pieces. “Participants associated puzzle pieces with imperfection, incompletion, uncertainty, difficulty, the state of being unsolved, and, most poignantly, being missing.”

- Autism Speaks does not speak for us.

- Presume competence. “To not presume competence is to assume that some individuals cannot learn, develop, or participate in the world. Presuming competence is nothing less than a Hippocratic oath for educators.”

- “Functioning labels are useless for the autistic person.” They are harmful constructs.

- “Function labels are what others use to try to control us and act as gatekeepers to the things we need to survive and thrive. Functioning labels are weapons used against us.“

- “Children grow up. Autistic children are children. The development curve might have more turns, but it tends towards the same end point. Some parents use functioning labels as a way to show how many challenges one autistic has compared to another. The more challenges there are, the lower the grade is. These parents are missing the point. When we experience hard moments, it feels bad no matter how you grade us. Everything can simply stop “functioning” even if we are said to be “high-functioning”.“

- ‘Aside from the fact that these labels are arbitrary, divisive, imprecise, and inaccurate, they just don’t make sense. As someone (not me) brilliantly stated, “Low functioning means that your strengths are ignored; high functioning means that your deficits are ignored.”‘

- “Is Stephen Hawking low-functioning? Is being able to tie one’s shoes the pinnacle of human achievement?“

- “You don’t speak for everyone = be quiet. What about low functioning people? = be quiet. You’re high functioning = be quiet.”

- “When mothers and fathers hear the term low-functioning applied to their children, they are hearing a limited, piecemeal view of their child’s abilities and potential, ignoring the whole child. Even when a child is described as “high-functioning,” parents often point out that he continues to experience major challenges that educators and others too often minimize or ignore. When professionals apply these sorts of labels early in a child’s development, it can have the effect of unfairly predetermining a child’s potential: if “low,” don’t expect much; if “high,” she’ll do fine and doesn’t need support.“

- I am an agent, not a patient. Autistic is my identity, not a diagnosis

- “We’ve built this whole infrastructure about fixing folks, about turning people into passive recipients of treatment and service, of turning people into patients. But being a patient is the most disempowered place a human being can be. We have created a system that has you submit yourself, or your child, to patient-hood to access the right to learn differently. The right to learn differently should be a universal human right that’s not mediated by a diagnosis.”

- “We have a medical community that’s found a sickness for every single human difference. DSM keeps growing every single year with new ways to be defective, with new ways to be lessened.”

- “Disability’s no longer just a diagnosis; it’s a community.”

- “Noncompliance is a social skill”.

- “Prioritize teaching noncompliance and autonomy to your kids. Prioritize agency.“

- “Many behavior therapies are compliance-based. Compliance is not a survival skill. It makes us vulnerable.“

- “It’s of crucial importance that behavior based compliance training not be central to the way we parent, teach, or offer therapy to autistic children. Because of the way it leaves them vulnerable to harm, not only as children, but for the rest of their lives.”

- Disabled kids “are driven to comply, and comply, and comply. It strips them of agency. It puts them at risk for abuse.” “The most important thing a developmentally disabled child needs to learn is how to say “no.” If they only learn one thing, let it be that.”

- “Our non-compliance is not intended to be rebellious. We simply do not comply with things that harm us. But since a great number of things that harm us are not harmful to most neurotypicals, we are viewed as untamed and in need of straightening up.“

- ‘What I am against are therapies to make us stop flapping our hands or spinning in circles. I am against forbidding children to use sign language or AAC devices to communicate when speech is difficult. I am against any therapy designed to make us look “normal” or “indistinguishable from our peers.” My peers are Autistic and I am just fine with looking and sounding like them.‘

- “When an autistic teen without a standard means of expressive communication suddenly sits down and refuses to do something he’s done day after day, this is self-advocacy … When an autistic person who has been told both overtly and otherwise that she has no future and no personhood reacts by attempting in any way possible to attack the place in which she’s been imprisoned and the people who keep her there, this is self-advocacy … When people generally said to be incapable of communication find ways of making clear what they do and don’t want through means other than words, this is self-advocacy.”

- “We don’t believe that conventional communication should be the prerequisite for your loved one having their communication honored.“

- Compassion and acceptance are practical and effective magic. They remedy a lot of problems and contribute to psychological safety. Acceptance matters.

- “A big part of our susceptibility to issues like anxiety has to do with how we were slowly socialized, either implicitly or explicitly, to believe that an autistic lifestyle is something that is defective and therefore needs fixing. A recent Independent article sums up the strong link between lack of autism acceptance and the development of mental health disorders in autistic people: Research shows that lack of acceptance externally from others and internally from the self significantly predicts depression and anxiety in young adults with autism. “

- “We also reject the equation that accepting autism and disability means giving up. Research consistently shows that autism acceptance leads to better mental health for parents as well as autistic people themselves. Evidence is mounting that acceptance and accommodation provide a more reliable path to increased capability and independence than fighting autism or disability does. Acceptance isn’t a cure, but it does facilitate recognition and support of abilities that often go unrecognized and under-valued. We are better off when not only our disabilities, but our real abilities, are recognized.”

- “Compassion is not coddling.” Disabled and neurodivergent people are always edge cases, and edge cases are stress cases. The logistics of disability and cognitive difference in an ableist and inaccessible world are exhausting, often impossible.

- Part of compassion is recognizing the structural realities of marginalized people and rejecting narratives of resentment. Design is tested at the edges.

- “No one knows best the motion of the ocean than the fish that must fight the current to swim upstream.”

- “By focusing on the parts of the system that are most complex and where the people living it are the most vulnerable we understand the system best.”

- “When we build things – we must think of the things our life doesn’t necessitate. Because someone’s life does.”

- “That’s why we’ve chosen to look at these not as edge cases, but as stress cases: the moments that put our design and content choices to the test of real life.”

- “Instead of treating stress situations as fringe concerns, it’s time we move them to the center of our conversations-to start with our most vulnerable, distracted, and stressed-out users, and then work our way outward. The reasoning is simple: when we make things for people at their worst, they’ll work that much better when people are at their best.”

- ‘People who enter services are frequently society’s most vulnerable–people who have experienced extensive trauma, adversity, abuse, and oppression throughout their lives. At the same time, I struggle with the word “trauma” because it signifies some huge, overt event that needs to pass some arbitrary line of “bad enough” to count. I prefer the terms “stress” and “adversity.” … Our brains and bodies don’t know the difference between “trauma” and “adversity”–a stressed fight/flight state is the same regardless of what words you use to describe the external environment. I’m tired of people saying “nothing bad ever happened to me” because they did not experience “trauma.” People suffer, and when they do, it’s for a reason.‘

- “Written communication is the great social equalizer.” Phones are stressful and exclusionary. If you work with neurodivergent kids, keep in mind that their parents are likely neurodivergent. Most of the autistic parents “you encounter will not be diagnosed, and may indeed be oblivious to their own social and communication difficulties. By making your systems and processes more adapted to the needs of autistic mothers, you will be supporting not only undiagnosed mothers (and fathers) but other adults with additional needs.” “Online communication is a valid accommodation for the social disability that comes with being Autistic. We need online interaction.” “Online communication for autistics has been compared to sign language for the deaf. Online, we are able to participate as equals. Our disability is often invisible and we are treated like humans. It provides much needed human contact otherwise denied us. ” “Thin slice studies showed that people prejudge us harshly in just micro-seconds of seeing or hearing us (though we fare better than neurotypical subjects when people only see our written words).” Both kids at school and adults at work benefit from backchannels. Bring the backchannel forward. “This kind of technology supports the shy user, the user with speech issues, the user having trouble with the English Language, the user who’d rather be able to think through and even edit a statement or question before asking it.“

- Autistic self-advocates are very concerned about behaviorism and deficit ideology, particularly ABA. “My experience with special education and ABA demonstrates how the dichotomy of interventions that are designed to optimize the quality of life for individuals on the spectrum can also adversely impact their mental health, and also their self-acceptance of an autistic identity. This is why so many autistic self-advocates are concerned about behavioral modification programs: because of the long-term effects they can have on autistic people’s mental health. This is why we need to preach autism acceptance, and center self-advocates in developing appropriate supports for autistic people. That means we need to take autistic people’s insights, feelings, and desires into account, instead of dismissing them.” With behaviorism, “the literal meaning of the words is irrelevant when you’re being abused. When I was a little girl, I was autistic. And when you’re autistic, it’s not abuse. It’s therapy.” “The abuse of autistic children is so expected, so normalised, so glorified that many symptoms of trauma and ptsd are starting to be seen as autistic traits.“

- “Great minds don’t always think alike. To face the challenges of the future, we’ll need the problem-solving abilities of different types of minds working together.” The social model, for both minds and bodies, is essential to inclusive design, collaboration, and learning. We are responsible for humanizing flow in the systems we inhabit, and we need the social model to do it.

- Inform the spaces you control with neurodiversity and the social model of disability so that they welcome and include all minds and bodies. Provide quiet spaces for high memory state zone work where people can escape sensory overwhelm, slip into flow states, and enjoy a maker’s schedule. Provide social spaces for collaboration and camaraderie. Create cave, campfire, and watering hole zones. Create Cavendish space. Fill our learning spaces with choice and comfort, instructional tolerance, continuous connectivity, and assistive technology. Design for agency, collaboration, intrinsic motivation, and real life.

- Interaction badges are useful tools. Their red, yellow, green communication indicators map to my cave, campfire, and watering hole moods. The cave, campfire, watering hole and red, yellow, green reductions are a useful starting place when designing for neurological pluralism. When we design for pluralism, we design for real life, for the actuality of humanity.

- The language and narratives of accommodation are harmful. Accommodation is not acceptance. You can’t have an inclusive-by-default culture when your mindset and framing are strictly accommodation. Accommodation encourages the harmful ableist tropes of people being “special” and “getting away with” extra “privileges” and “advantages”. Accommodation is fertile ground for zero-sum thinking, grievance culture, and the politics of resentment. We can’t build inclusion on current notions of accommodation. Inclusion requires acceptance.

- Segregation is always wrong, and “special” segregates. “The word “special” is used to sugar-coat segregation and societal exclusion – and its continued use in our language, education systems, media etc serves to maintain those increasingly antiquated “special” concepts that line the path to a life of exclusion and low expectations. A child with “special needs” catches the “special bus” to receive “special assistance” in a “special school” from “special education teachers” to prepare them for a “special” future living in a “special home” and working in a “special workshop”. Does that sound “special” to you?“

- “Fair is not when everyone has the same thing, but when everyone has what they need.” Insistence on “equality” or “sameness” of treatment is usually ableist and exclusionary in outcome. “Sameness of treatment” drives neurodivergent and disabled people out of school, out of work, and out of society. This sort of equality is anti-acceptance and anti-inclusion. Fairness for us requires an equity or needs-based notion of fairness.

- We are not here for your inspiration. Don’t objectify us for your feels. “Inspiration porn is a term used to describe society’s tendency to reduce people with disabilities to objects of inspiration.” “We are all too aware of the risk of being filmed for someone’s feel-good story (or for someone to mock, but that could be another post). We already face enormous pressure to not ask for help – to be the “supercrip” and “overcome” our disabilities – and the risk of being a viral story is yet another reason we might avoid asking for help when we need it.”

- Fix injustice, not kids. “It essentially boils down to whether one chooses to do damage to the system or to the student.”

- Don’t be an Autism Warrior Parent. “Autism Warrior Parents (AWPs) insist on supporting their autistic kids either by trying to cure them, or by imposing non-autistic-oriented goals on them — rather than by trying to understand how their kids are wired, and how that wiring affects their life experience. Ironically, an AWP’s choices not only interfere with their own kid’s happiness and security, but contribute to social biases that prevent autistic people of all ages from getting the supports they need. Worst of all, by publicly rejecting their own children’s autism and agency, and by tending to hog the autism spotlight, AWPs are partially responsible for the public’s tendency to sympathize with parents rather than autistic kids — which, at its most extreme, can mean excusing parents and caretakers who murder their autistic charges.” “Autism Warrior Parents are those who, for whatever reason, refuse to accept their autistic child’s actual reality and needs, and instead put their energies into absolute change or control of that child.” “AWPs have also turned the internet into an autism information minefield, which is especially frustrating given that online resources are often invaluable for families who lack access to therapists, specialists, and other key resources.” “Enmeshed in fear and loathing toward autism, they condition themselves to forget that their children are fully human, and that humans respond best to compassion.”

- Our community recommends NeuroTribes to everyone working with other humans. NeuroTribes changed the conversation about what it is to be human. It is a history of the 20th Century through the lens of the dispossessed and misunderstood. It is a trip through anguish and horror and a celebration of the minds that survived to make modernity.

- Autistic people are the experts on autism. Listen to us.

Am I Autistic?

If you are wondering whether you are Autistic, spend time amongst Autistic people, online and offline. If you notice you relate to these people much better than to others, if they make you feel safe, and if they understand you, you have arrived.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Requiring diagnosis was counter to trans liberation and acceptance. The exact same is true of Autism.

Dr. Devon Price

Self diagnosis is not just “valid” — it is liberatory. When we define our community ourselves and wrest our right to self-definition back from the systems that painted us as abnormal and sick, we are powerful, and free.

Dr. Devon Price

You can pursue formal diagnosis if you want, for legal protection and educational access. It will never be what makes you Autistic. If you’re uncertain whether you are, meet more of us and join in community with us. We need each other far more than we need psychiatric approval.

Where I saw the first irrefutable proof of myself, though, so many others saw a referendum.

I Overcame My Autism and All I Got Was This Lousy Anxiety Disorder: A Memoir

I spent twenty-seven years trying to convince people that I was normal enough to accept, or at least leave alone, and no one ever fully bought it. When I finally knew why that experiment was such an ongoing failure, though, few believed that either. I was using it as an excuse. I was exaggerating. I was faking. I was not as autistic as someone else someone knew and was, therefore, not really autistic.

These comparisons only ever go in one direction. No one has ever said to me, “Temple Grandin is a successful scientist, writer and public speaker, and you have the career of a mildly plucky freelancer half your age. You can’t possibly be autistic.” I suspect that this is because no one is genuinely trying to weigh what they know about me against a set of diagnostic criteria, or fit me into their greater understanding of autistics in the world. What people are really doing when they’re trying to determine if I’m really autistic is figuring out if I make them uncomfortable or sad enough to count. If I show any coping skills, any empathy, any likability, any fun essentially any humanity–I complicate the narrative too much and usually end up ignored.

I Overcame My Autism and All I Got Was This Lousy Anxiety Disorder: A Memoir

This separation between real autistics and people who are “just quirky,” “just awkward” or “almost too high functioning to count” is a mental dance that non-autistics have to do whenever they’re confronted with a 3-D autistic human being in the flesh. Otherwise everything they’ve ever thought, everything they’ve ever been told about us, starts to seem a little monstrous.

I Overcame My Autism and All I Got Was This Lousy Anxiety Disorder: A Memoir

Most of us are haunted by the sense there’s something “wrong” or “missing” in our lives—that we’re sacrificing far more of ourselves than other people in order to get by and receiving far less in return.

Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity

What’s Next After Diagnosis/Self-Identification?

Whether medically diagnosed or self-diagnosed, self-identified, what’s next?

First, welcome!

This book is about what it means to be a part of the autistic community. Autistic people wrote this book. Some autistic people are just learning about their autism. We wanted to welcome them and give them a lot of important information all in one place.

This book talks about what autism is and how it affects our lives. It talks about our history, our community, and our rights. We wrote this book in plain language so that more people can understand it.

We wrote this book for autistic people, but anyone can read it. If you are not autistic, this book can help you support autistic people you know. If you are wondering whether you might be autistic, this book can help you learn more. If you are autistic, think you might be autistic, or if you want to better understand autistic people, this book is for you.

Welcome to the autistic community!

Welcome to the Autistic Community – Autistic Self Advocacy Network

“You’re not broken, and this is nothing new. It’s how you are, how you’ve always been, and this is just the name of it. You are wonderful!”

Lorraine

Be gentle with yourself as you review your life through a new perspective. You will likely be reviewing your life through your new set of “eyes” for a significant time. This could potentially bring about some sadness and anger, especially if your autistic traits were ignored by the people around you for a very long time. I know, for myself I was angry at the many professionals that I sought out to help me over the years. Be relieved, you’ve found who you are, had unanswered questions answered and it can only get better from here on out.

Kimberly

Next, this video series from Autistimatic provides a compassionate and nuanced onboarding.

Community Resources

Autism. Nearly 80 years on from the original misunderstandings in the 1940s. So, what’s changed, in research? Almost everything.

Autism: Some Vital Research Links.

Ann Memmott maintains a list of vital autism research links.

AutisticSciencePerson maintains a Resources page for:

- autistic maskers of any gender

- newly diagnosed autistic people/questioning if autistic

- neurotypicals and non-autistics

- parents of autistic people

Mykola Bilokonsky maintains the Public Neurodiversity Support Center.

Pete Wharmby maintains a “Neurodivergent Community” Twitter list.

The Spectrum Gaming community maintains Autism Understood, a website about autism, for autistic young people.

Autistic Sparrow maintains a resource page.

Neurodiverse Connection maintains a Resource Library.

We maintain a page confronting bad autism research.

We also maintain a page celebrating useful autism research.

Respectfully Connected: Advice to Teachers and Parents of Autistic Kids

But embracing autism or accepting autistic people for who they are does not mean ignoring the legitimate challenges. Far from it. It simply means acknowledging that autistic people and all neurodivergent people deserve the same civil rights as others, which advocates like Sam Crane at ASAN have articulated. Often, they are the ones who want to include it in the larger movement for disability rights and request more accommodations. Many of them recognize that some autistic people have more impairments than others and want to find ways to help autistic people with comorbidities like epilepsy and gastrointestinal issues. Embracing autistic people and acknowledging their needs are not mutually exclusive ideas; they are complementary. For the most part, the increase in diagnoses has given autistic people something important: a community.

We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

“Autism is a unique condition in medicine because it confers powerful disability and really extraordinary exceptionality,” he told me back in 2015. “Our duty in autism is not to cure but to relieve suffering and to maximize each person’s potential.”

We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

We follow and recommend this advice:

Instead of intensive speech therapy – we use a wonderful mash-up of communication including AAC, pictures scribbled on notepads, songs, scripts, and lots of patience and time.

Instead of sticker charts and time outs, or behavior therapy – we give hugs, we listen, solve problems together, and understand and respect that neurodivergent children need time to develop some skills

Instead of physical therapy – we climb rocks and trees, take risks with our bodies, are carried all day if we are tired, don’t wear shoes, paint and draw, play with lego and stickers, and eat with our fingers.

Instead of being told to shush, or be still- we stim, and mummies are joyful when they watch us move in beautiful ways.

Respectfully Connected | #HowWeDo Respectful Parenting and Support

A parent’s advice to a teacher of autistic kids

- Be patient. Autistic children are just as sensitive to frustration and disappointment in those around them as non-autistic children, and just like other children, if that frustration and disappointment is coming from caregivers, it’s soul-crushing.

- Presume competence. Begin any new learning adventure from a point of aspiration rather than deficit. Children know when you don’t believe in them and it affects their progress. Instead, assume they’re capable; they’ll usually surprise you. If you’re concerned, start small and build toward a goal.

- Meet them at their level. Try to adapt to the issues they’re struggling with, as well as their strengths and special interests. When possible, avoid a one-size-fits all approach to curriculum and activities.

- Treat challenges as opportunities. Each issue – whether it’s related to impulse control, a learning challenge, or a problem behavior – represents an opportunity for growth and accomplishment. Moreover, when you overcome one issue, you’re building infrastructure to overcome others.

- Communicate, communicate, communicate. For many parents, school can be a black box. Send home quick notes about the day’s events. Ask to hear what’s happening at home. Establish communication with people outside the classroom, including at-home therapists, grandparents, babysitters, etc. Encourage parents to come in to observe the classroom. In short, create a continuous feedback loop so all members of the caregiver team are sharing ideas and insights, and reinforcing tactics and strategies.

- Seek inclusion. This one’s a two-way street: not only do autistic children benefit from exposure to their non-autistic peers, those peers will get an invaluable life lesson in acceptance and neurodiversity. The point is to expose our kids to the world, and to expose the world to our kids.

- Embrace the obsession. Look for ways to turn an otherwise obsessive interest into a bridge mechanism, a way to connect with your students. Rather than constantly trying to redirect, find ways to incorporate and generalize interests into classroom activities and lessons.

- Create a calm oasis. Anxiety, sensory overload and focus issues affect many kids (and adults!), but are particularly pronounced in autistic children. By looking for ways to reduce noise, visual clutter and other distracting stimuli, your kids will be less anxious and better able to focus.

- Let them stim! Some parents want help extinguishing their child’s self-stimulatory behaviors, whether it’s hand-flapping, toe-walking, or any number of other “stimmy” things autistic kids do. Most of this concern comes from a fear of social stigma. Self-stimulatory behaviors, however, are soothing, relaxing, and even joy-inducing. They help kids cope during times of stress or uncertainty. You can help your kids by encouraging parents to understand what these behaviors are and how they help.

- Encourage play and creativity. Autistic children benefit from imaginative play and creative exercises just like their non-autistic peers, misconceptions aside. I shudder when I think about the schools who focus only on deficits and trying to “fix” our kids without letting them have the fun they so richly deserve. Imaginative play is a social skill, and the kids love it.

I just want to do what is best for my child. Can this notion of Neurodiversity help me do that?

Yes, absolutely! The notion of Neurodiversity can allow you to embrace your child for who they are, and it can empower you to look for respectful solutions to everyday problems. It can also help you to raise your child to feel empowered and content in their own skin.

Do you think I am ableist? I thought I was helping my child…

That is hard for me to hear. I didn’t think I was ableist and it hurts to be told I am.

That’s fair enough. However, if you want to do what is best for your child you will need to move past that in order to begin to shed this ableism from your everyday reactions and choices.

How does it feel to be autistic?

That is really complex and difficult to answer. I cannot explain that in as much depth as would give you a good knowledge of it, however there are so many autistic writers you can look to for guidance on that. If you are asking me to to describe how I experience life, as compared to how you experience life, this is a huge question.

Is there a quick way to understand all this?

Respectfully Connected | Neurodiversity Paradigm Parenting FAQs

1. Learn from autistic people

2. Tell your child they are autistic

3. Say NO to all things stressful & harmful

4. Slow down your life

5. Support & accommodate sensory needs

6. Value your child’s interests

7. Respect stimming

8. Honour & support all communication

9. Minimise therapy, increase accommodations & supports

10. Explore your own neurocognitive differences

Respectfully Connected | 10 ‘Autism Interventions’ for Families Embracing the Neurodiversity Paradigm

It’s people’s own attitudes that often lie behind alleged ‘autistic behaviour’.

Ann Memmott

Useful research.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12671-022-01933-4#Tab1

When parents are calm, their autistic children are more likely to be able to regulate & recover from brain events (meltdown, shutdown).

Yep. As I often say, it’s people’s own attitudes that often lie behind alleged ‘autistic behaviour’

Decades of hyper-aggressive individuals who are scathing about autistic people in their care has shown me why the autistic person displays a lot of distress behaviour round them.

Self reflection is vital. All communication is a two way process, not autistic ‘fault’

Staff who were calmer, in schools with #autistic young people, found the yp relaxed too, and distress behaviours dropped to zero. Small study but no surprise, eh.

Previous research supporting these same findings, both for parents and for teachers. And linking to #Synergy training by @AT_Autism & the low-arousal training approaches by @studioIII

This stuff actually works.

Wouldn’t it be embarrassing if the answer to most autistic ‘behaviour’ was in fact for people to calm down, round us, instead of spending $billions on painful, exhausting and pointless stuff that does nothing but add profits to some companies? Mmm?

Meeting our children where they are doesn’t mean giving up on them. It means seeing them as a whole person, broadening their access to communication, helping them figuring out their unique learning styles, helping them figuring out their sensory profile, and putting accommodations in place. When we work with our children instead of against them, instead of trying to fix them, we end up with happier children. And that is a goal worth striving for.

Meghan Ashburn, I Will Die On This Hill

Image source: Non-ABA Evidence Based Practice | Therapist Neurodiversity Collective

Applying ABA in therapeutic practice is entirely unacceptable to us. Therapist Neurodiversity Collective does things differently:

- Zero ABA, including positive reinforcement

- Zero desensitization, tolerance, or extinction targets or approaches

- Zero neuronormative goals (masking of sensory systems, monotropic interests systems, anxiety)

- Zero training neurotypical social skills

We take the research framework from developmental and relationship-based therapy models, use our knowledge of client and caregiver perspectives (no goals for masking, eye contact, whole body listening, appearing neurotypical, etc.), and apply our clinical background to implement therapy practices which are respectful, culturally competent, trauma-sensitive and empathetic.

Non-ABA Evidence Based Practice | Therapist Neurodiversity Collective

We presume competence.

We believe that AAC has no prerequisites.

We respect sensory differences.

We respect body autonomy.

Most importantly, we continually learn from our neurodivergent mentors as to what therapy approaches and methodologies are respectful and uphold human rights and self-determination.

Non-ABA Evidence Based Practice | Therapist Neurodiversity Collective

It’s pretty easy to tell if someone finds a therapy helpful or not, regardless of whether they are verbal. How is the person’s mood? Do they find therapy sessions distressing? If it’s the latter, maybe that kind of therapy isn’t the best fit. Being unable to speak and being unable to communicate at all are not the same thing. Listen to your clients, especially the ones who do not speak. They’re the ones who need you to listen the most.

So what kind of therapy is compatible with neurodiversity? The answer is surprisingly simple. Is your therapy designed to improve communication, reduce anxiety and/or redirect harmful behaviors? That’s not in opposition to the neurodiversity paradigm at all. Neurodiversity does not mean that we want a hall pass to smash windows or bite our fingers until we bleed. It doesn’t mean that we are ignoring the reality of our lives. It doesn’t mean that those of us who are verbal and/or who need fewer supports aren’t thinking about our nonverbal peers. It means understanding, to paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr., that a riot is the language of the unheard. Listen to us. Please.

ADVICE FOR THERAPISTS FROM A NEURODIVERSITY ADVOCATE

Our findings reveal the longitudinal impact of mindful parenting on child psychopathology. In particular, our findings indicate that mindful parenting is associated with lower levels of child internalizing and externalizing symptoms through lower levels of maladaptive parent–child interactions.

The dispositional tendency toward mindfulness may enable parents of children with ASD to practice mindful parenting (Wang et al., 2022). Mindful parenting refers to providing intentional, present-centered, and non-judgmental attention to parent–child interactions (Bögels et al., 2010; Kabat-Zinn & Kabat-Zinn, 1997). Specifically, mindful parents pay close attention and listen carefully to their children (Duncan et al., 2009). They also bring an open and non-judgmental attitude and show empathy and compassion toward their children (Duncan et al., 2009). Furthermore, they are aware of their children’s and their own emotional states and regulate their own affective reactions during their interactions with their children (Duncan et al., 2009).

Mindful parenting may enhance parent–child closeness in families of children with ASD (Lippold et al., 2015). Parent–child closeness refers to the presence of intimacy, positive affection, and self-disclosure in the parent–child relationship (Paulson et al., 1991). As mindful parents attend closely and listen carefully to their children, they can understand their children’s thoughts and feelings more accurately and show greater sensitivity and responsiveness to their children’s concerns and needs (Lippold et al., 2021). Also, as these parents bring an open and non-judgmental stance to the attributes and behaviors of their children, they can show higher levels of parental acceptance and compassion (Duncan et al., 2015). Furthermore, as they are able to regulate their own emotions in parenting, they can parent calmly and consistently (Benton et al., 2019). In this way, they can create a warm and loving atmosphere for their parent–child interactions (Duncan et al., 2009).

These findings suggest that parents who incorporate mindful awareness into their parenting processes are likely to have better parent–child relationships. With less destructive parent–child interactions, children with ASD may have fewer emotional and behavioral problems.

The negative associations of mindful parenting with child internalizing and externalizing symptoms suggest that a mindful way of parenting may be linked to lower levels of child psychopathology. This finding is consistent with earlier studies showing that higher levels of mindful parenting were associated with lower levels of child emotional and behavioral problems (Aydin, 2022; Cheung et al., 2019). The finding is also in line with prior studies reporting the positive impact of mindful parenting on child well-being and functioning (Cheung et al., 2021; Medeiros et al., 2016). Given the benefits of mindful parenting to child development, practitioners should facilitate parents of children with ASD to cultivate mindfulness and apply it in parenting (Ho et al., 2021).

This finding suggests that mindful parenting may shield against child psychopathology through fewer negative parent–child interactions (Han et al., 2021; Parent et al., 2016).

Specifically, our model indicates that mindful parenting may be associated with lower levels of child emotional and behavioral problems through lower levels of maladaptive parent–child interactions. Importantly, our model points to the utility of a family process perspective in conceptualizing and understanding the evolvement of psychological problems in children with ASD (Chan et al., 2022a).

Longitudinal Impact of Mindful Parenting on Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder | SpringerLink

Further evidence produced from this line of research suggests that mindfulness training, when provided for the benefit of parents, can significantly alter behavioral trends demonstrated by the individuals whom they support.

Mindfulness Training for Staff in a School for Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities: Effects on Staff Mindfulness and Student Behavior | SpringerLink

Don’t take away your child’s voice; take away their suffering. ABA is a cruel response to aggressive behavior. Meet that behavior with love, calm, support, and an investigative search for the source of your child’s struggle instead. Learn why your child is getting so stressed out that they are frightening the people around them, and help make your child’s life calmer, safer, and happier. That is what you were hoping ABA therapy would do, but I am here to tell you that ABA cannot do that. It is your role as a loving parent and you don’t need a behaviorist. You just need the love and compassion you already have for your beautiful child. Dealing with aggression really is a situation in life where love conquers all. Go forth now and vanquish suffering with curiosity, compassion, and calmness.

IF NOT ABA THERAPY, THEN WHAT?

When we slowed all of the therapies down to a crawl, let go of our expectations about development, and remembered that Evie is actually a kid that deserves to be a, you know, kid, Evie’s quality of life improved. And so did ours as parents. I know that there is a tremendous amount of pressure to “intervene” when a kid is not doing things according to the book. I know there is a tremendous amount of guilt, that you feel as a parent when you’re not doing enough for your kid. But enough can become too much really quickly. And I would argue that the current prescription for early intervention is an overdose. If I could go back and do it again, we would do a bit of pt and a bit of speech. And we would do the hippotherapy and aquatic therapy because Evie loved those and because they turned out to be the most beneficial. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

I’ve come to hate the word intervention. Evie doesn’t need an intervention. I don’t want to stop behavior. I want to learn the cause of it. Then I want to support her or accommodate her as necessary. When we look at behaviors as needing intervention rather than understanding, we cut out the most important piece of the puzzle.

the case for backing the frick off

How I Do It: AUTISM AND AAC: FIVE THINGS I WISH I HAD KNOWN by Deanne Shoyer

The target of intervention is not autistic children, but their social and physical environments. Autistic children [need to be] supported in families and communities to develop as unique and valued human beings, without conforming to the developmental trajectory of their neurotypical peers.

Briannon Lee

Get respectfully connected. Learn more on our Learning and Education Access pages.

How to Create an Autism Inclusive Environment

Back Off

I want to talk about the potential benefits of less therapies. I want to talk about eliminating interventions. I want to talk about why what is called “prompting” is actually forcing and how that should be stopped.

Basically, I want to make the case for backing the eff off Autistic kids–Autistic people in general, actually.

All I’m asking for is a SINGLE study that provides any evidence that ABA is any more effective than kids spending equivalent time with someone who knows nothing about ABA.

If they can’t show that, how on Earth do they think they can justify a multi-billion dollar industry? What?

Pretty much everything an autistic child does, says, doesn’t do or doesn’t say is pathologised and made into a way to invent a ‘therapy’ for it.

It’s actually _hell_ to experience.

We should stop doing this and start learning about autism.

The Basics of Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

- Presume Competence — Presuming competence means assuming an individual can learn, think, and understand, even when we may not have evidence available to confirm this.

- Promote Autonomy — When we promote autonomy with children and young people, we are giving them the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and supporting them to have a voice in all aspects of their lives.

- Respect all Communication Styles — To be neurodiversity affirming regarding communication, we need to consider all communication as valid and acknowledge that there are many ways that individuals communicate beyond spoken language.

- Be Informed by Neurodivergent Voices — Evidence-based practice incorporates research, clinical knowledge and expert opinion, along with client preferences, to provide effective support, and who better to provide expert opinion than neurodivergent individuals themselves.

- Take a Strengths-Based Approach — A strengths-based approach not only considers an individual’s personal strengths, but also how conditions in their environment can be adapted to remove barriers and facilitate access to desired activities.

- Honor Neurodivergent Culture — As therapists, we can honor our client’s neurodivergence by giving them a safe space to be themselves, accommodating their needs and being accepting of their neurodivergent style of being.

- Tailor Support to Individual Needs — Tailoring an approach specifically to a client’s needs involves recognising that due to differences in sensory processing, cognition, communication, and perception, neurodivergent individuals experience the world differently to the neurotypical population, and as such are likely to need different therapeutic supports.

The 5 As of Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

- Authenticity – A feeling of being your genuine self. Being able to act in a way that feels comfortable and happy for you.

- Acceptance – A process whereby you feel validated as the person you are, not only by yourself but by others too.

- Agency – A feeling of control over actions and their consequences in your day-to-day life.

- Autonomy – A state of being self-directed, independent, and free. Being able to act on your ideas and wants.

- Advocacy – To speak for yourself, communicate what is important to you and your needs or the needs of others.

The 6 Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Practice

- Safety: Prioritising the physical, psychological and emotional safety of young people.

- Trustworthiness: Explaining what we do and why, doing what we say we will do, expectations being clear and not overpromising.

- Choice: Young people are supported to be shared decision makers and we actively listen to the needs and wishes of young people.

- Collaboration: The value of young people’s experience is recognised through actively working alongside them and actively involving young people in the delivery of services.

- Empowerment: We share power as much as we can, to give young people the strongest possible voice.

- Cultural consideration: We actively aim to move past cultural stereotypes and biases based on, for example, gender, sexual orientation, age, religion, disability, geography, race or ethnicity.

The NEST Approach for Supporting Young People in Distress

- Nurture — The very first thing we need to remember is to help a young person feel safe – remember that experiencing a meltdown is incredibly scary. If someone is upset/ stressed/ having a meltdown, focusing on helping them to feel calm is important as people cannot think logically at this time. Until they feel safe, there is no next productive step.

- Empathise — If someone is struggling or has reached crisis point, it is important to assume there is a good reason why and to try to understand their perspective, plus any reasoning for their current struggle.

- Sharing Context — Why do we want to problem solve with the young person? We need to show that how the young person feels is important to us, but also share the perspectives of other people so they can fully understand the situation if the situation is a result of miscommunication.

- Teamwork — Most services and settings focus on a system of rewards and punishments for changing behaviour. We understand that when young people are struggling we need to address the root cause. The best way to do this is by working together.

Source: The NEST Approach for Supporting Young People in Distress

Understanding Motivation and Behaviour through Self-Determination Theory

- Autonomy — Self-Determination Theory (SDT) underscores the importance of autonomy in motivation and behaviour. Autistic young people are more likely to engage positively when they have choices and control over their actions. Our school environment is designed to provide opportunities for autonomy, such as choosing activities and setting goals.

- Competence — Competence is another key component of SDT. We recognize the importance of providing opportunities for young people to develop and showcase their skills and abilities. This fosters a sense of competence and achievement. We take an asset-based approach: identifying key strengths that our pupils have and fostering these strengths rather than solely focusing on their challenges. As a result, pupils feel empowered to further develop their own skill sets and recognise their unique contributions.

- Relatedness — Relatedness, the third component of SDT, emphasises the significance of positive social connections. Our school promotes acceptance, teamwork, and relationship-building among participants, creating a sense of belonging and relatedness.

- Integration with Our Principles — The principles of SDT are integrated into our behaviour management approach. By supporting autonomy, competence, and relatedness, we enhance motivation, engagement, and overall wellbeing of our students.

Source: Understanding Motivation and Behaviour through Self-Determination Theory

Key Principles When Supporting Autistic People

- Autism Acceptance — In many spaces and places autism is seen as a negative thing. Autism is not a ‘disorder’ or a ‘burden’, it is simply a difference. Just like every other brain type, the autistic brain has its negatives and its positives.

- Young people often need to recover from their negative experiences to be able to thrive — Young people need time, and the right support to recover. Especially since outside of safe spaces, they may still be exposed daily to trauma and stress.

- Young people do well if they can — We believe that all young people do well if they can. Everyone wants to thrive, do well, and no one wants to cause upset with others or break rules. If someone is struggling – there is a reason why they are struggling. We can work together to identify reasons why and what may help.

- Co-regulation — Young people need repeated experiences of co-regulation from a regulated adult before they can begin to self-regulate. They may also not know how to regulate by themselves and we may be a key resource to help them create ways that work for them.

- Self-Care — Self care is vital – it isn’t possible to properly care for young people when you are overwhelmed yourself.

- Neurodiversity affirming practice — We believe in the 5 As of neurodiversity affirming practice, from The Autistic Advocate. This is a strengths and rights-based approach to affirm a young person’s identity, rather than focusing on ‘fixing’ a young person because of their neurotype.

Top 5 Neurodivergent-Informed Strategies

- Be Kind — Take time to listen and be with people in meaningful ways to help bridge the Double Empathy Problem (Milton, 2012). Be embodied and listen not only to people’s words but also to their bodies and sensory systems.

- Be Curious — Be informed by the voices of those with lived experience, learn from and act on the neurodiversity-affirming research that is evolving and that validates the inner experiences of neurodivergent people. For Autistic/ ADHD people, this includes understanding how the theory of monotropism and embracing people’s natural flow state can support well-being (Murray et al., 2005) and (Heasman et al., 2024).

- Be Open — Be open and be compassionate. It has been shown that neurodivergent people are at a higher risk of mental difficulties and suicide (Moseley, 2023). Think about the weight a neurodivergent person carries in a society that values neuronormative ways of being and consider the impact of masking on people’s mental health (Pearson and Rose, 2023).

- Be Radically Inclusive — We need a strength-based approach to care and education. (Laube 2023) suggested we must acknowledge and respect a person’s neurodivergence, learn how it affects them, and value their unique experiences. We need individualised support instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach. We should try to reduce and challenge stigma and stereotypes and provide radically inclusive spaces for people to thrive in.

- Be Neurodiversity-Affirming — Take time to read about the neurodiversity paradigm “Neurodiversity itself is just biological fact!” (Walker, 2021); a person is neurodivergent if they diverge from the dominant norms of society. “The Neurodiversity Paradigm is a perspective that understands, accepts and embraces everyone’s differences. Within this theory, it is believed there is no single ‘right’ or ‘normal’ neurotype, just as there is no single right or normal gender or race. It rejects the medical model of seeing differences as deficits.” (Edgar, 2023)

Autistic SPACE: A Novel Framework for Meeting the Needs of Autistic People

- Sensory needs — Autistic people experience the world differently (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). Sensory sensitivities are common to almost all autistic people (MacLennan et al, 2022), but the pattern of sensitivities varies (Lyons-Warren and Wan, 2021). Autistic people can be sensory avoidant, sensory seeking or both (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020); hypo- or hyper-reactivity to any sensory modality is possible (Tavassoli et al, 2014) and a person’s sensory responsiveness can vary depending on circumstances (Strömberg et al, 2022). A ‘sensory diet’ provides scheduled sensory input which can aid physical and emotional regulation (Hazen et al, 2014).

- Predictability — Autistic people need predictability and may experience extreme anxiety with unexpected change (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). This underlies the autistic preference for routine and structure.

- Acceptance — Beyond simple awareness, there is a pressing need for autism acceptance. A neurodiversity-affirmative approach recognises that neurodevelopmental differences are part of the natural range of human development (Shaw et al, 2021) and acknowledges that attempts to make autistic people appear non-autistic can be deeply harmful (Bernard et al, 2022). This does not exclude inherent or environmental disability.

- Communication — Autistic people communicate differently. Many use fluent speech, but may experience challenges with verbal communication at times of stress or sensory overload (Cummins et al, 2020; Haydon et al, 2021). Others do not speak or may use few words (Brignell et al, 2018). Many non-speaking or minimally speaking autistic people use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods, including visual cards, writing or electronic devices, which should be facilitated (Zisk and Dalton, 2019).

- Empathy — Despite common assumptions to the contrary, autistic people do not lack empathy (Fletcher-Watson and Bird, 2020). It may be experienced or expressed differently, but this is perhaps the most damaging misconception about autism (Hume and Burgess, 2021). In fact, many autistic people report experiencing hyper-empathy, to the point of being unable to deal with the onslaught of emotions, leading to ‘shutdown’ in order to cope (Hume and Burgess, 2021). A bi-directional, mutual misunderstanding occurs between autistic and non-autistic people, termed ‘the double empathy problem’ (Milton, 2012). As such, non-autistic healthcare providers may struggle to empathise with autistic patients, particularly where communication training is generally conducted from a neuronormative, non-autistic perspective, in which the needs of autistic people are not considered (Bradshaw et al, 2021).

Source: Autistic SPACE: A Novel Framework for Meeting the Needs of Autistic People