Learning Pathways

Understanding neurodiversity and disability justice means stepping into unfamiliar stories and frameworks. In “Learning Pathways,” we guide you through experiential and educational journeys that unpack everything from monotropism and systemic power to inclusive education and healthcare. These pathways are not merely informational — they are invitations to walk in our shoes, challenge assumptions, and grow in understanding at your own pace.

This website is an encyclopedia of disability and difference.

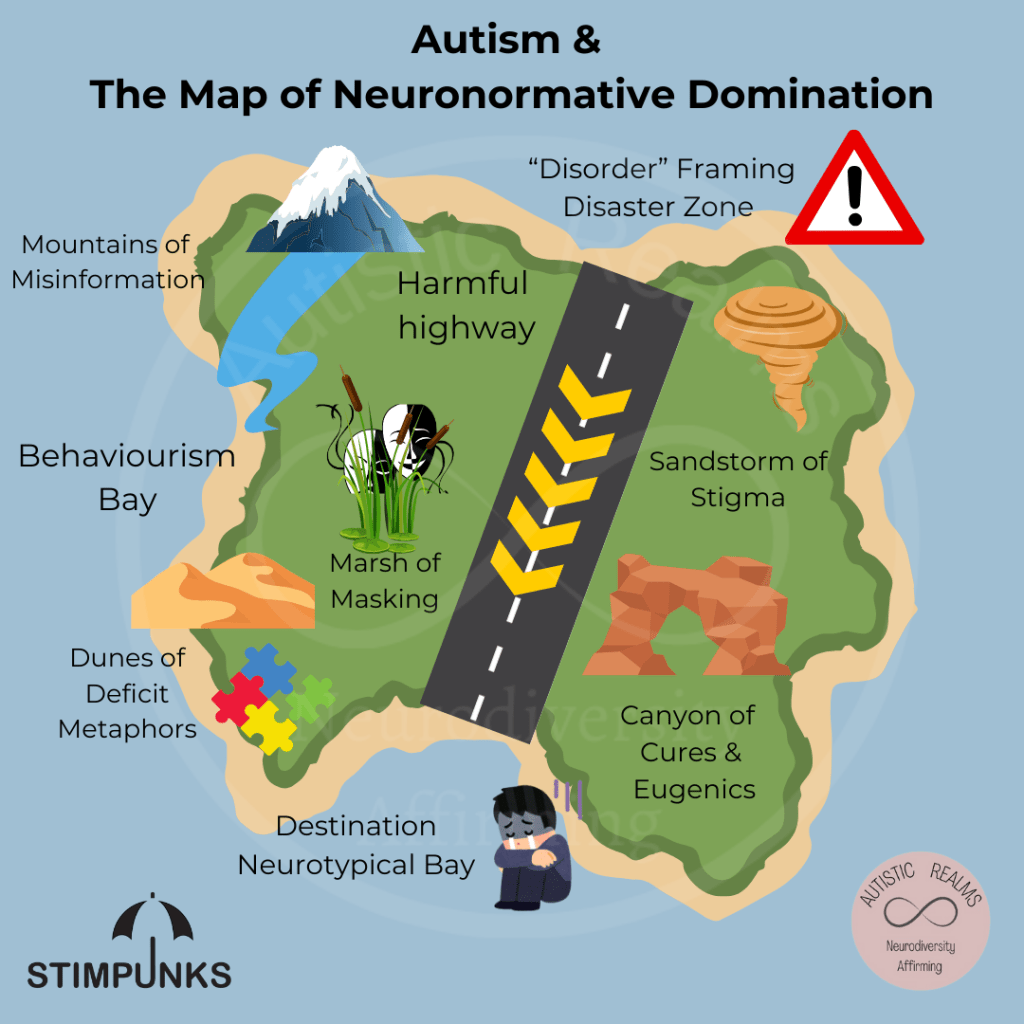

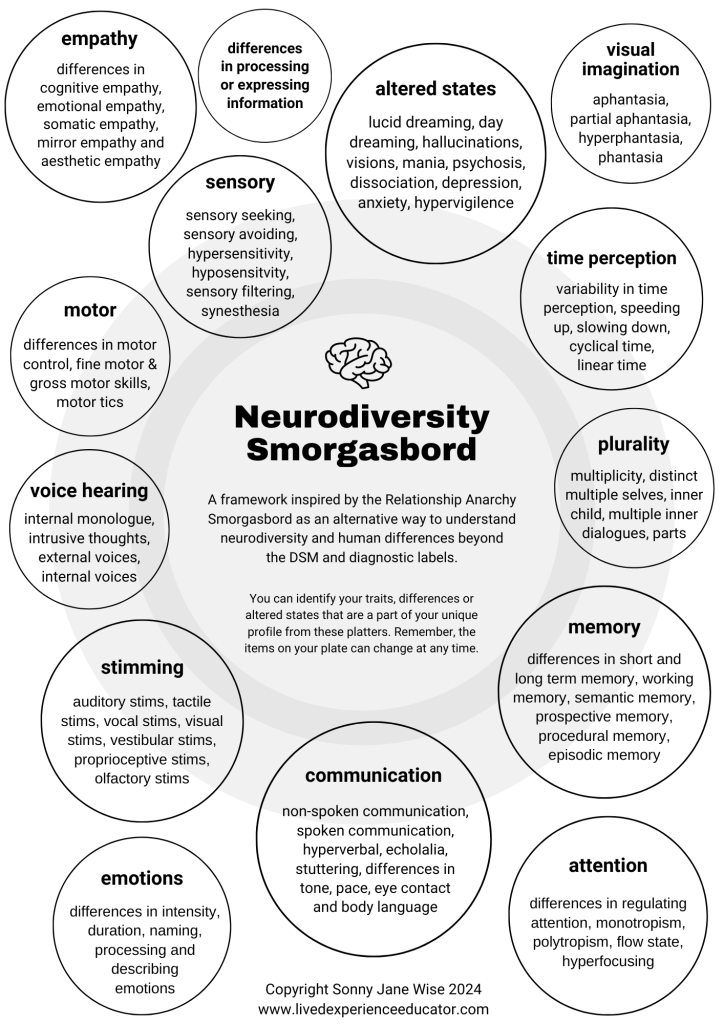

Learn about spiky profiles, school-induced anxiety, neuronormative domination, obstacles to neurodiversity, behaviorism, the double empathy problem, monotropism, the neurodivergent umbrella, the neurodiversity Smorgasbord, and more.

Learn about yourself.

Learn about your family.

Learn about your friends, co-workers, patients, and students.

We offer validation for thirsty souls yearning to be seen, heard, and understood.

We offer words on your behalf, ones which call out to include you.

We offer community and belonging.

When you or your kid is diagnosed as neurodivergent, almost all of the professional advice you get from education and healthcare is steeped in deficit ideology and the pathology paradigm.

There are better ways.

Learn more with our Autism, Education, and Healthcare Learning Pathways.

Autism Pathway

Autistic? Think you might be autistic? Got autistic friends, family, patients, clients, co-workers? Here are some pathways through our website to learn about autism and autistic ways of being.

Education Pathway

What might education look like in a system in which the acceptance, inclusion, and accommodation of every sort of bodymind represents an unquestioned baseline?

This pathway guides us through the ableist reality of mainstream education into progressive, neuroaffirming education that scales from home to entire school districts.

Healthcare Pathway

Our advocacy for neurodiversity affirming practice in healthcare seeks to improve delivery of healthcare to neurodivergent and disabled consumers. We seek to improve health practitioner competency through education and training programs and bring attention to the inadequacies of care in order to advance systemic change.

We see lots of neurodiversity-lite solutions applied to healthcare that fail to advance systemic change. We’re here for real structural change steeped in neurodiversity and disability justice.

Join us on our healthcare learning pathway. Learn how to adopt neurodiversity affirming practice that meets our needs into care settings.

Reframing Our Ways of Being Pathway

Not having the vocabulary to describe yourself and your loved ones is a tragedy. Our story of reframing disability and difference starts on our front page and continues via the “Continue” button at the bottom of each page in the journey.

Those who work their way through this pathway will have the understanding of neurodiversity, disability, neurodivergent learning, and neurodivergent ways of being needed to become the allies we need.

This pathway includes lots of art, music, poetry, and more from our community.

Take the journey. Reframe, and gain vocabulary for you and yours.

- Authenticity Is Our Purest Freedom

- Everything that was normally supposed to be hidden was brought to the front.

- Learning Pathways: Take a Walk in Our Shoes

- Our Story: Challenging the Norm and Changing the Narrative

- Take Them Together: Neurodiversity and Disability Justice

- Our Umbrella: It Is Time to Celebrate Our Interdependence!

- Reframe Disability and Difference: We’re Going to Rewrite the Narratives

- Happy Flappy: Let’s Bolster Against Stress and Pass Bodily Survival Knowledge Down

- An Encyclopedia of Disability and Difference

Systems of Power Pathway

Our “Systems of Power” learning pathway will help you recognize and name the systems of power.

Our learning pathways take you on a walk in our shoes.

Take a Walk in Our Shoes

This powerful animation reveals that the barriers and solutions lie not within the young person, but in the school environment, its ethos and in peer and teacher relationships and attitudes.

Walk in My Shoes – The Donaldson Trust

We have turned classrooms into a hell for neurodivergence. Telling young neurodivergent people struggling to attend school to be more resilient is profoundly inappropriate.

Erin’s experiences shine a light on issues beyond her control that could be resolved by others; by listening and by showing they care. She could not have done more. Telling young autistic people struggling to attend school to be more resilient is profoundly inappropriate, if what you are really asking is for them to keep going under circumstances they should not be asked to endure. We need to change the circumstances.

Walk in My Shoes – The Donaldson Trust

Education Access: We’ve Turned Classrooms Into a Hell for Neurodivergence

The number of autistic young people who stop attending mainstream schools appears to be rising.

Walk in My Shoes – The Donaldson Trust

My research suggests these absent pupils are not rejecting learning but rejecting a setting that makes it impossible for them to learn.

We need to change the circumstances.

Trainers are rejecting behaviorism because it harms animals emotionally and psychologically.

Empty Pedagogy, Behaviorism, and the Rejection of Equity | Human Restoration Project | Chris McNutt

What does that say about classrooms that embrace it?

This “science-driven” mantra has been seen before through eugenics.

Therefore, eugenics is an erasure of identity through force, whereas radical behaviorism is an erasure of identity through “correction.”

This all assumes a dominant culture that one strives to unquestionably maintain.

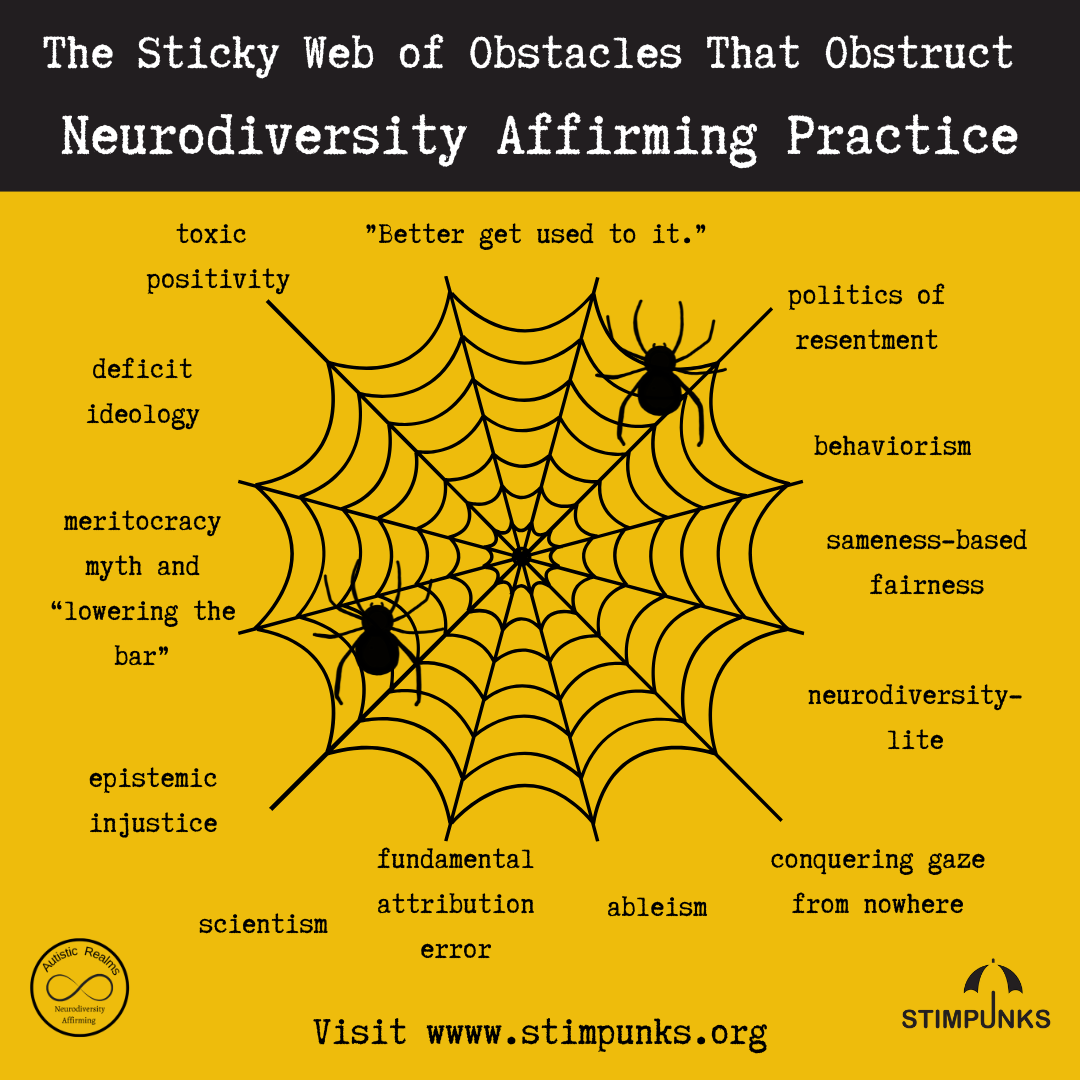

Our path is littered with obstacles.

Our community of neurodivergent and disabled people encounters the following narratives over-and-over with dreadful regularity. They are fundamental contributors to the Double Empathy Extreme Problem (DEEP) we neurodivergent and disabled people must attempt to bridge. We make the attempt in hope that, once we do all the work of building the bridge, you will endeavor to meet us halfway.

Get over the bridge by recognizing these frames in your own thinking.

framing = mental structures that shape the way we see the world

Obstacles to DEI-AB and Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

(links are to our glossary, where you can learn much more)

- politics of resentment

- sameness-based fairness

- fundamental attribution error

- conquering gaze from nowhere

- toxic positivity

- neurodiversity-lite

- scientism

- epistemic injustice

- behaviorism

- ableism

- deficit ideology

- ”Better get used to it.”

- meritocracy myth

- “lowering the bar”

politics of resentment = manipulations of status anxiety; organization of interest groups based on perceived deprivation or the threat of deprivation

sameness-based fairness = notion of fairness where everyone gets the same thing rather than each getting what they need

fundamental attribution error = to underestimate the impact of situational factors and to overestimate the role of dispositional factors in controlling behaviour

conquering gaze from nowhere = the interpretation of objectivity as neutral and not allowing for participation or stances; an uninvolved, uninvested approach that claims objectivity to “represent while escaping representation”

toxic positivity = belief that success happens to good people and failure is just a consequence of a bad attitude rather than structural conditions

neurodiversity-lite = using neurodiversity as a buzzword; a way to profit from the appropriation of a human rights movement; a cottage industry for therapists, clinics, and companies to sell their associated products, classes, books, and training to the public without having a clue about neurodiversity

scientism = the belief that science is the only route to useful knowledge

epistemic injustice = where our status as knowers, interpreters, and providers of information, is unduly diminished or stifled in a way that undermines the agent’s agency and dignity

behaviorism = a dehumanizing mechanism of learning that reduces human beings to simple inputs and outputs

ableism = a system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness

deficit ideology = a worldview that explains and justifies outcome inequalities by pointing to supposed deficiencies within disenfranchised individuals and communities

better get used to it = preparing people for oppression by oppressing them

meritocracy myth = a widely held but false assertion that individual merit is always rewarded; the myth of meritocracy is one of the longest lasting and most dangerous falsehoods in American life

lowering the bar = a racist, sexist, and ableist narrative with no basis in reality that represents diversifying hiring pipelines, attracting candidates from underrepresented groups, and supporting them in the workplace as “lowering the bar” by hiring less-qualified individuals

The logistics of disability and difference in a structurally ableist and inaccessible world poisoned by bad framing are exhausting, often impossible. We are perpetual hackers, mappers, and testers of our systems by necessity of survival.

We need your help. We need you to help us bridge the Double Empathy Extreme Problem (DEEP). To do that, we all must change our framing. You cannot be an ally to us until you perceive beyond the framing listed above.

double empathy problem = the mutual incomprehension that occurs between people of different dispositional outlooks (Milton 2013); when people with very different experiences of the world interact with one another, they will struggle to empathise with each other (Milton, 2018)

double empathy extreme problem (DEEP) = mass societal disconnect from each other, our own bodyminds, and nature that obstructs empathizing across cultural, sexual, political, religious, neurodivergent, and any other cross-section of differences (Edgar, 2024)

One group will always find it difficult to put themselves in the position of another group’s experience, because of their different experiences, and therefore will always find it difficult to empathize with each other.

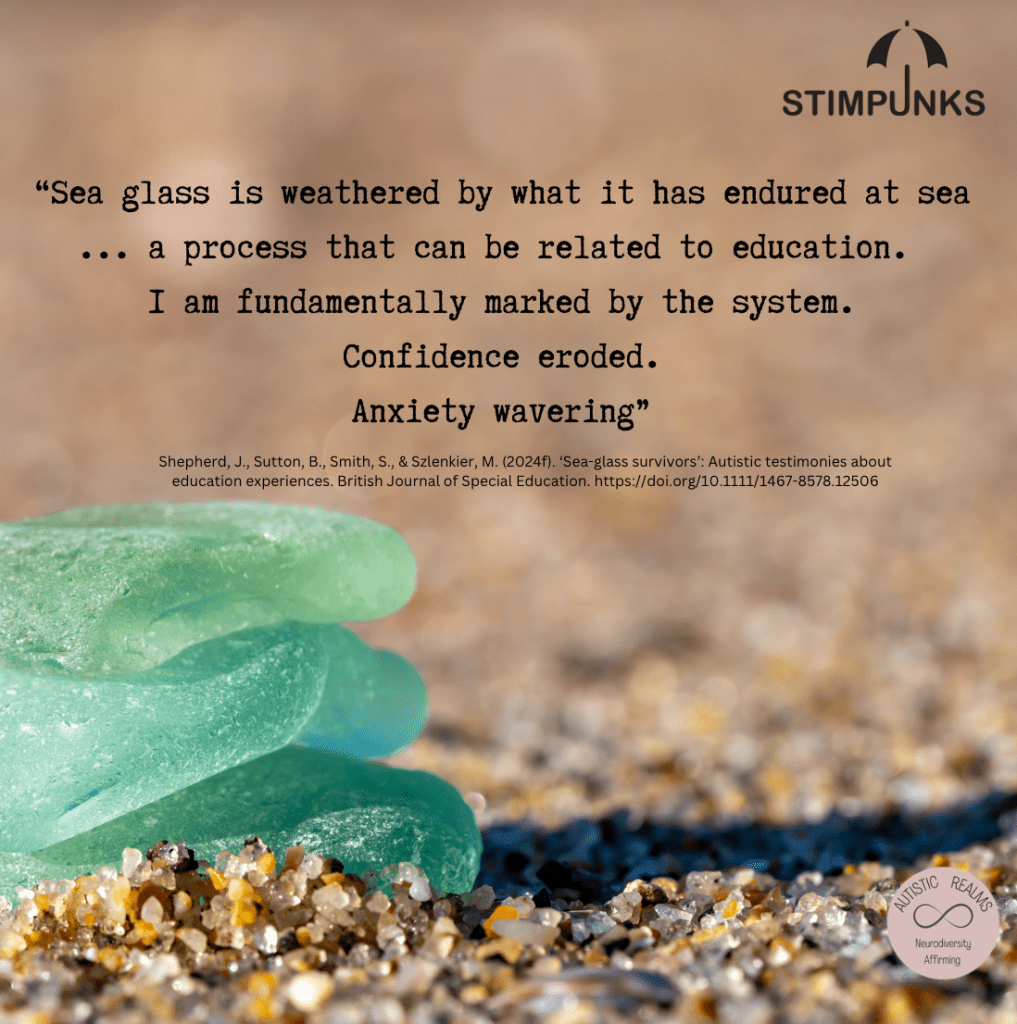

We are fundamentally marked by the system.

Meanwhile, we are being ground down. We are fundamentally marked by the system.

“Sea Glass Survivors” is one of the most beautifully powerful pieces of research we have ever read about the autistic experience of unmet needs in the education system.

Sea glass is weathered by what it has endured at sea (Figure 2), a process that can be related to education. I am fundamentally marked by the system. Confidence eroded. Anxiety wavering. Now, overcompensation is a form of self-preservation, taking breaks is still unnatural and achievements come with a little sense of pride. Just as sea glass is ground down by every knock, its eventual form is a sum of its aquatic endurance.

Positive memories of education have been flooded by the negative. Instead, I course through the ocean propelled to defy the lack of expectations imposed on me, but also by defiance, to disprove those who wrote me off.

However, a life tussling with the tide-against the odds— has also left its mark more positively. The researcher, practitioner, colleague and peer I am today refuses to entertain ideas or set up environments that make some people (neurominority) feel less intelligent, inadequate or inferior, than others (neuromajority), just as my secondary school English teacher and other curious individuals did. In many ways, these moments anchor my practice.

‘Sea‐glass survivors’: Autistic testimonies about education experiences – Shepherd – British Journal of Special Education – Wiley Online Library

We are especially marked by behaviorism.

Behaviorism is a dehumanizing mechanism of learning that reduces human beings to simple inputs and outputs. There is an ever-growing body of research suggesting that behaviorism is not only harmful to how we learn, but is also oppressive, ableist, and racist.

More Human Than a Ladder or Pyramid: Psychology, Behaviorism, and Better Schools | Human Restoration Project | Chris McNutt

Plenty of policies and programs limit our ability to do right by children. But perhaps the most restrictive virtual straitjacket that educators face is behaviorism — a psychological theory that would have us focus exclusively on what can be seen and measured, that ignores or dismisses inner experience and reduces wholes to parts. It also suggests that everything people do can be explained as a quest for reinforcement — and, by implication, that we can control others by rewarding them selectively.

Behaviorism measures the surface, badly.

- Behaviorism is a theory of learning that focuses on observable behaviors and environmental stimuli.

- Behaviorism only looks at observable behavior which can be measured. It doesn’t take into account thoughts, genetics, anxiety, trauma, health, or emotions because those things cannot be measured.

- The more our attention is fixed on the surface, the more we slight students’ underlying motives, values, and needs.

- Behaviors are just the protruding tip of the proverbial iceberg. What matters more than “What?” or “How much?” is “How come?”

- Behaviorists ignore, or actively dismiss, subjective experience – the perceptions, needs, values, and complex motives of the human beings who engage in behaviors.

- Behaviourism is a reduction of dimensions which creates an illusion of scientific worth by focussing only on what we can ‘know for sure’.

- Ultimately behaviorism provides a simplistic lens that can’t see beyond itself.

- Why is the doctrine of behaviorism still being used, at all?

- Behaviorism is a repudiation, an almost willful dismissal, of subjective experience.

- It’s time we outgrew this limited and limiting psychological theory. That means attending less to students’ behaviors and more to the students themselves.

- How can ABA be the gold-standard for autism when it ignores everything we know about autism?

- The focus on surface behavior, without seeming to understand or be concerned about the complexity, or even the simple dichotomy of volitional versus autonomic (stress response) and the use of outdated, compliance based, animal based behaviorism (which has no record of long term benefits) continues to fail our country’s students.

- Radical Behaviourism is broadly seen by psychology professionals as a simplistic and restrictive theory which is useful in certain situations but cannot sum up the entirety of the human experience. It doesn’t even satisfactorily answer some questions about behaviours seen in animals.

- Findings did not reveal compelling evidence that ABA is an approach that improves the quality of life or wellbeing of autistic people.

- It’s been refuted so overwhelmingly.

The primary legacy of ABA is trauma.

- “I have ABA (Applied Behavioural Analysis) therapy and I hate it, probably the worst part of my autism. Everyday I have someone come to my house wake me up and boss me around for 4 hours.”

- The problems associated with ABA run very deep. It is a human rights violation to continue to ignore and discount the voices of Autistic people about deeply traumatising and harmful “therapies” such as ABA.

- The behaviorist strategies caused a fracturing of identity and mental health problems.

- “I became a frightened passive prisoner in a world I was alienated from by their violent attempts to avoid seeing who I really was and what I may contribute to humankind.”

- ABA is a breeding ground for meltdowns. The only way ABA knows how to “train” a child, to “motivate” them (as if they were lacking in motivation before this), is to negate their needs or take away their joy.

- This is a child’s heart in fight or flight mode, constantly, that is being bombarded with all these instructions and prompting.

- Nearly half (46 percent) of the ABA-exposed respondents met the diagnostic threshold for PTSD, and extreme levels of severity were recorded in 47 percent of the affected subgroup.

- Adults and children both had increased chances (41 and 130 percent, respectively) of meeting the PTSD criteria if they were exposed to ABA.

- Current research has suggested ABA as causing a severe level of trauma from childhood participation.

- Autistic individuals continue to highlight the suffering felt through ABA’s inability to acknowledge the negativity inflicted through forceful coercion.

- To be punished for a stress response is harmful and traumatic.

- Adults who received ABA as children are at an increased risk of suicide and PTSD.

- The conditions created by ABA foster psychological ill-being.

- It focuses on training children by holding their sources of happiness hostage and using them as blackmail to get the children to meet goals which are not necessarily in the best interest of their emotional health.

- Behaviorism is harmful for vulnerable children, including those with developmental delays, neuro-diversities (ADHD, Autism, etc.), mental health concerns (anxiety, depression, etc.)

- Any reasonable observer cannot confidently deny that ABA is negatively affecting the autistic population.

- Compliance, learned helplessness, food/reward-obsessed, magnified vulnerabilities to sexual and physical abuse, low self-esteem, decreased intrinsic motivation, robbed confidence, inhibited interpersonal skills, isolation, anxiety, suppressed autonomy, prompt dependency, adult reliance, etc., continue to be created in a marginalized population who are unable to defend themselves.

- These children are the population that was chosen to be the subjects of an experimentally intense, lifelong treatment within a therapy where most practitioners are ignorant regarding the Autistic brain—categorically, this cannot be called anything except abuse.

ABA violates the fundamental tenets of bioethics.

- Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) … manifests systematic violations of the fundamental tenets of bioethics.

- Adult autistics who have undergone ABA have described as violating the fundamental tenets of bioethics, as well as the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- Autism advocates are fully justified in their concerns-the rights of autistic children and their parents are being regularly infringed upon.

- Employing ABA violates the principles of justice and nonmaleficence and, most critically, infringes on the autonomy of children and (when pushed aggressively) of parents as well.

- Radical behaviorism is an erasure of identity through “correction.” This all assumes a dominant culture that one strives to unquestionably maintain.

- PBS is not actually supported by Disabled People’s Organisations and allies. This is because PBS does not meet human rights, has a poor quality evidence base and its risks and harms are not understood.

- Providing a treatment that causes pain in exchange for no benefit, even if unknowingly, is tantamount to torture and violates the most basic requirement of any therapy: to do no harm.

- Autistics have been excluded from all committees, panels, boards, etc., charged with developing, directing, and assessing ABA research and treatment programs.

Behaviorist education is ableist education.

- Behaviorist education is ableist education.

- We are in a sort of remediation industrial complex, where there’s all sorts of services and treatments and interventions to make the square peg fit the round hole. Parents are relentlessly told that that’s their job.

- This is a top-down, power over, authoritarian approach that is not in alignment with the rest of the goals of the educational system that is designed to teach children to think and learn.

- The most restrictive virtual straitjacket that educators face is behaviorism.

ABA violates autonomy.

- ABA violates autonomy insofar as it coercively closes off certain paths of identity formation.

- ABA violates autonomy by coercively modifying children’s patterns of behavior to be misaligned with their preferences, passions, and pursuits. Such superficial change is a pervasive form of interference that compromises children’s present and future autonomy.

- Pretty much everything an autistic child does, says, doesn’t do or doesn’t say is pathologised and made into a way to invent a ‘therapy’ for it. It’s actually hell to experience.

- Our non-compliance is not intended to be rebellious. We simply do not comply with things that harm us. But since a great number of things that harm us are not harmful to most neurotypicals, we are viewed as untamed and in need of straightening up.

- Many autistic persons who have participated in ABA anecdotally reported feelings of belittlement, expressed the loss of behavioural autonomy, recalled external pressure to “not be themselves”, and viewed reward or consequence systems as a form of control.

Autistic adults loathe ABA.

- It is nothing short of stunning to learn just how widely and intensely ABA is loathed by autistic adults who are able to describe their experience with it.

- The majority of the 620 survey respondents from Europe were strongly against the use of ABA and ABA-based methods with autistic people.

- Yet the vast majority of autistic people when polled (typically 97%) oppose ABA including and especially those who went through it as children.

ABA is badly out of date.

- ABA therapy is badly out of date, scientifically speaking.

- Until ABA updates its scientific methods, its functions of behavior, and incorporates modern day psychology – including neurology, child development, educational psychology, and other vital research – it cannot be considered to be a safe, effective, or ethical field.

- Research in ABA continues to neglect the structure of the autistic brain, the overstimulation of the autistic brain, the trajectory of child development, or the complex nature of human psychology.

- Radical Behaviourism is considered out-of-date by modern psychologists.

- The future of Autism and other conditions ABA professes to treat is very bleak.

I would never treat a dog that way.

- Trainers are rejecting behaviorism because it harms animals emotionally and psychologically. What does that say about classrooms that embrace it?

- Dog trainers don’t talk about systematically altering behaviour as if the dog weren’t a thinking, feeling, sentient being.

- A good dog trainer doesn’t extinguish behaviours which improve the dog’s mental health and happiness. But an ABA practitioner may not think twice before doing this to a human child.

- Dog trainers understand that dogs need to chew and bark and dig, but ABA therapists don’t understand that autistic children need to repeat words and sentences, flap their hands, and sit quietly rocking in a corner when things get too much.

- So if it isn’t sufficient to properly train a dog, is it sufficient in educating a child?

- I would never treat a dog that way.

We have turned classrooms into a hell for neurodivergence.

Education Access: We’ve Turned Classrooms Into a Hell for Neurodivergence – Stimpunks Foundation

For those of you in our shoes, we prepared some “Why Sheets” to help you clear the way.

Why Sheets

We are creating free, downloadable, editable parent/carer resources to help students and families advocate for themselves. These sheets include open license letters and resources people can download and edit/personalize. We call these “Why Sheets“.

Our why sheets concisely explain why some education and parenting practices are good and others bad. They explain using formats like selected quotes, bulleted lists, and one idea per line.

- Hoodie – [Student name] will wear a plain hoodie in the future rather than the school blazer. Here’s why.

- Positive Greetings at the Door – Many neurodivergent people have difficulties when entering a classroom that implements Positive Greetings at the Door (PGD). Here’s why.

- Behaviorism – Behaviorism is ableist. Here’s why.

- Alternatives to ABA – ABA is bad, very bad. Here’s what to do instead.

Join us under the umbrella.

☂️ The Neurodivergent Umbrella

- ADHD (Kinetic Cognitive Style)

- DID & OSDD

- ASPD

- BPD

- NPD

- Dyslexia

- CPTSD

- Dyspraxia

- Sensory Processing

- Dyscalculia

- PTSD

- Dysgraphia

- Tourette’s Syndrome

- Stuttering & Cluttering

- Anxiety & Depression

- Personality Disorders/Conditions

- Bipolar

- Autism

- Epilepsy

- OCD

- ABI

- Tic Disorders

- Schizophrenia

- Misophonia

- HPD

- Down Syndrome

- Synesthesia

- Panic Disorders/Conditions

- Developmental Language Disorder/Condition

- Developmental Co-ordination Disorder/Condition

- Hearing Voices

Non-exhaustive list

About the Neurodivergent Umbrella

Friendly reminder that neurodivergent is an umbrella term that is inclusive and not exclusive – this means mental illnesses are considered neurodivergent.

Sonny Jane Wise (@livedexperienceeducator)

A few things:

Neurodivergent is an umbrella term for anyone who has a mind or brain that diverges from what is seen as typical or normal.

Neurodivergent is a term created by Kassiane Asasumasu, a biracial, multiply neurodivergent activist. Neurodiversity is a different term created by Judy Singer, an autistic sociologist.

Neurodivergent doesn’t just refer to neurological conditions, this is an inaccurate idea based on the prefix of neuro.

Identifying as neurodivergent is up to the individual and we don’t gatekeep or enforce the term.

Disability and neurodivergence are broad umbrellas that include many people, possibly you. The neurodivergent umbrella includes a diversity of inherent and acquired differences and spiky profiles. Many neurodivergent people don’t know they are neurodivergent. With our website and outreach, we help people get in touch with their neurodivergent and disabled identities. We respect and encourage self-diagnosis/self-identification and community diagnosis. #SelfDxIsValid, and our website can help you understand your ways of being.

If you are wondering whether you are Autistic, spend time amongst Autistic people, online and offline. If you notice you relate to these people much better than to others, if they make you feel safe, and if they understand you, you have arrived.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Self diagnosis is not just “valid” — it is liberatory.

Requiring diagnosis was counter to trans liberation and acceptance. The exact same is true of Autism.

Dr. Devon Price

Self diagnosis is not just “valid” — it is liberatory. When we define our community ourselves and wrest our right to self-definition back from the systems that painted us as abnormal and sick, we are powerful, and free.

Dr. Devon Price

Our Ways of Being

Most humans are average in all functional skills and intellectual assessment, some excel at all, some struggle in all and some have a spiky profile, excelling/average/struggling. The spiky profile may well emerge as the definitive expression of neurominority, within which there are symptom clusters that we currently call autism, ADHD, dyslexia and DCD; some primary research supports this notion.

Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults | British Medical Bulletin | Oxford Academic

Knowing about “spiky profiles” and “splinter skills” is important to understanding and accommodating neurodivergent ways of being.

Spiky Profiles and Splinter Skills

Understanding spiky profiles, learning terroir, collaborative niche construction, and special interests is critical to fostering neurological pluralism.

There is consensus regarding some neurodevelopmental conditions being classed as neurominorities, with a ‘spiky profile’ of executive functions difficulties juxtaposed against neurocognitive strengths as a defining characteristic.

Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults | British Medical Bulletin | Oxford Academic

One of the primary things I wish people knew about autism is that autistic people tend to have ‘spiky skills profiles:’ we are good at some things, bad at other things, and the difference between the two tends to be much greater than it is for most other people.

Autistic Skill Sets: A Spiky Profile of Peaks and Troughs » NeuroClastic

This is what life is like when you have a spiky profile: a phenomenon whereby the disparity between strengths and weaknesses is more pronounced than for the average person. It’s characteristic among neuro-minorities: those who have neurodevelopmental conditions including autism and ADHD. When plotted on a graph, strengths and weaknesses play out in a pattern of high peaks and low troughs, resulting in a spiky appearance. Neurotypical people tend to have a flatter profile because the disparity is less pronounced.

Autism And The Spiky Profile. When you excel at some things and… | Autistic Discovery

Because we are bad at some things, people often expect us to be bad at other things; for example, they see someone failing to conform with social expectations, and assume that person has impaired intelligence. But because we are good at some things, people are often impatient when we’re not as skilled or need support in other areas.

Sometimes people talk about these islands of ability as ‘splinter skills’ — often autistic people are really very good at things we’re good at. Mostly the skills are the result of putting a lot of work in because we’re interested in it, not that we always have much control over where our interest takes us.

Autistic Skill Sets: A Spiky Profile of Peaks and Troughs » NeuroClastic

…the psychological definition refers to the diversity within an individual’s cognitive ability, wherein there are large, statistically-significant disparities between peaks and troughs of the profile (known as a ‘spiky profile’, see Fig. 1). A ‘neurotypical’ is thus someone whose cognitive scores fall within one or two standard deviations of each other, forming a relatively ‘flat’ profile, be those scores average, above or below. Neurotypical is numerically distinct from those whose abilities and skills cross two or more standard deviations within the normal distribution.

Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults | British Medical Bulletin | Oxford Academic

Neurodivergent Ways of Being

Not every neurodivergent person will relate to all of these things. There are lots of different ways to be neurodivergent. That is okay!

- Spiky Profile

- Alexithymia

- Asynchronous Communication

- Autistic Language Hypothesis

- Autistic Rapport

- Burnout

- Canary

- Dandelions, Tulips, and Orchids

- Demand Avoidance

- Dolphining

- Echolalia

- Executive Function

- Exposure Anxiety

- Eye Contact

- Fawn

- Fidgeting

- Food Aversion

- Gestalt Learning

- Hyperlexia

- Interoception

- Justice Sensitivity

- Meerkat Mode

- Meltdown

- Monotropic Spiral

- Monotropic Split

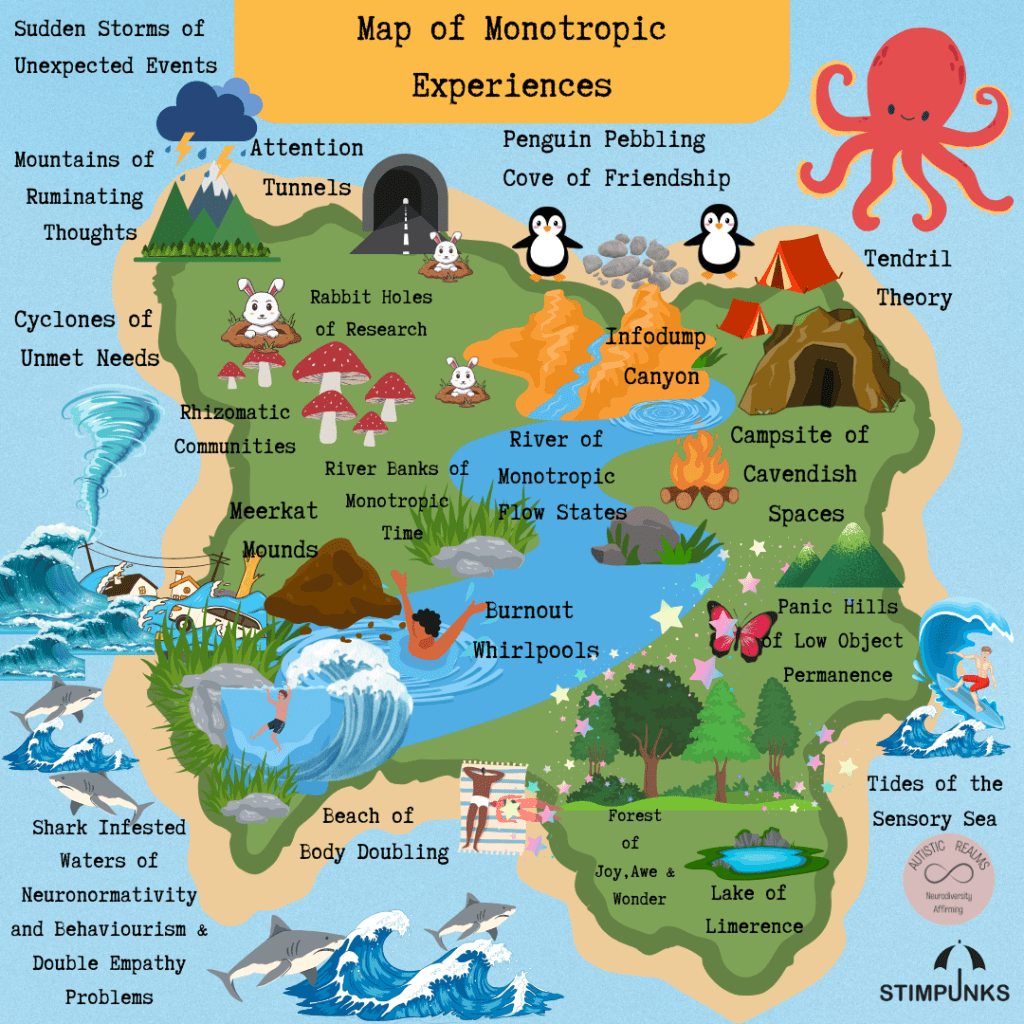

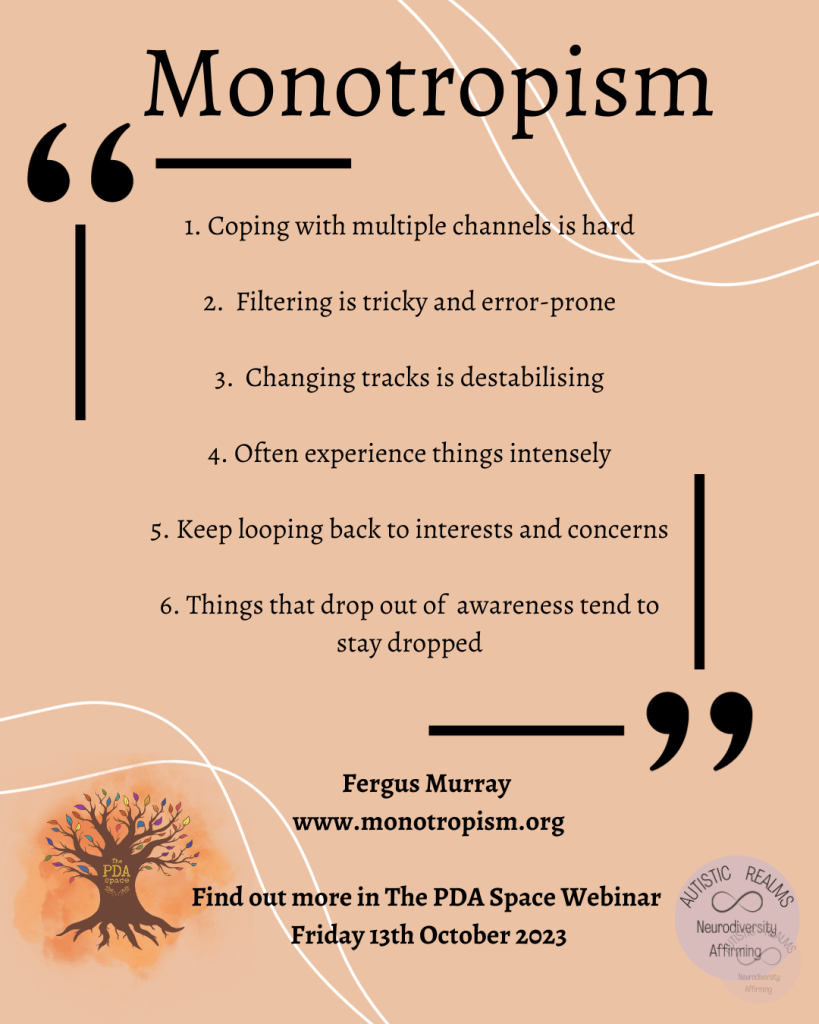

- Monotropism

- Neuroception

- Neuroqueer

- Neurospicy

- Noncompliance

- Nonspeaking

- Phone Calls

- Play

- Problem Behavior

- Processing Time

- Queer

- Rabbit Hole

- Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

- Rumination

- Samefood

- Self-Injurious Stimming

- Sensory Hell

- Sensory Trauma

- Situational Mutism

- Sleep

- Sparkle Brain

- Special Interest

- SpInfodump

- Stim Listening

- Stimming

- Stim-Watching

- Support Swapping

- Very Grand Emotions

- Weird

- Neuroception and Sensory Load: Our Complex Sensory Experiences

- Perceptual Worlds and Sensory Trauma

- The Five Neurodivergent Love Locutions

The Five Neurodivergent Love Locutions

The Five Neurodivergent Love Locutions

- Infodumping – Talking about an interest or passion of yours and thus sharing information, usually in detail and at length

- Parallel Play, Body Doubling – Parallel play is when people do separate activities with each other, not trying to influence each others behavior.

- Support Swapping, Sharing Spoons – Accommodating and supporting each other within a community. Asking, offering, and receiving help among people who “get it”.

- Deep Pressure: Please Crush My Soul Back Into My Body – Regulating with deep pressure input such as through swaddles, weighted blankets, and hugs.

- Penguin Pebbling: “I found this cool rock, button, leaf, etc. and thought you would like it” – Penguins pass pebbles to other penguins to show they care. Penguin Pebbling is a little exchange between people to show that they care and want to build a meaningful connection. Pebbles are a way of sharing SpIns, both inviting people into yours and encouraging other’s. SpIns are a trove for unconventional gift giving.

Autistic ways of being are human neurological variants that can not be understood without the social model of disability.

Autistic ways of being are human neurological variants that can not be understood without the social model of disability.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

If you are wondering whether you are Autistic, spend time amongst Autistic people, online and offline. If you notice you relate to these people much better than to others, if they make you feel safe, and if they understand you, you have arrived.

Autistic people / Autists must take ownership of the label in the same way that other minorities describe their experience and define their identity. Pathologisation of Autistic ways of being is a social power game that removes agency from Autistic people. Our suicide and mental health statistics are the result of discrimination and not a “feature” of being Autistic.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Autistic inertia is similar to Newton’s inertia, in that not only do Autistic people have difficulty starting things, but they also have difficulty in stopping things. Inertia can allow Autists to hyperfocus for long periods of time, but it also manifests as a feeling of paralysis and a severe loss of energy when needing to switch from one task to the next.

A communal definition of Autistic ways of being

Every autistic person experiences autism differently, but there are some things that many of us have in common.

- We think differently. We may have very strong interests in things other people don’t understand or seem to care about. We might be great problem-solvers, or pay close attention to detail. It might take us longer to think about things. We might have trouble with executive functioning, like figuring out how to start and finish a task, moving on to a new task, or making decisions.

Routines are important for many autistic people. It can be hard for us to deal with surprises or unexpected changes. When we get overwhelmed, we might not be able to process our thoughts, feelings, and surroundings, which can make us lose control of our body.- We process our senses differently. We might be extra sensitive to things like bright lights or loud sounds. We might have trouble understanding what we hear or what our senses tell us. We might not notice if we are in pain or hungry. We might do the same movement over and over again. This is called “stimming,” and it helps us regulate our senses. For example, we might rock back and forth, play with our hands, or hum.

- We move differently. We might have trouble with fine motor skills or coordination. It can feel like our minds and bodies are disconnected. It can be hard for us to start or stop moving. Speech can be extra hard because it requires a lot of coordination. We might not be able to control how loud our voices are, or we might not be able to speak at all–even though we can understand what other people say.

- We communicate differently. We might talk using echolalia (repeating things we have heard before), or by scripting out what we want to say. Some autistic people use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) to communicate. For example, we may communicate by typing on a computer, spelling on a letter board, or pointing to pictures on an iPad. Some people may also communicate with behavior or the way we act. Not every autistic person can talk, but we all have important things to say.

- We socialize differently. Some of us might not understand or follow social rules that non-autistic people made up. We might be more direct than other people. Eye contact might make us uncomfortable. We might have a hard time controlling our body language or facial expressions, which can confuse non-autistic people or make it hard to socialize.

Some of us might not be able to guess how people feel. This doesn’t mean we don’t care how people feel! We just need people to tell us how they feel so we don’t have to guess. Some autistic people are extra sensitive to other people’s feelings.- We might need help with daily living. It can take a lot of energy to live in a society built for non-autistic people. We may not have the energy to do some things in our daily lives. Or, parts of being autistic can make doing those things too hard. We may need help with things like cooking, doing our jobs, or going out. We might be able to do things on our own sometimes, but need help other times. We might need to take more breaks so we can recover our energy.

Not every autistic person will relate to all of these things. There are lots of different ways to be autistic. That is okay!

About Autism – Autistic Self Advocacy Network

Autism + environment = outcome. Understanding the sensing and perceptual world of autistic people is central to understanding autism.

I have written elsewhere about what I refer to as ‘the golden equation’ – which is:

Autism + environment = outcome

What this means in an anxiety context is that it is the combination of the child and the environment that causes the outcome (anxiety), not ‘just’ being autistic in and of itself. This is both horribly depressing but also a positive. It’s horribly depressing because it demonstrates just how wrong we are currently getting things, but positive in that there are all sorts of things we can do to change environmental situations to subsequently alleviate the anxiety.

Avoiding Anxiety in Autistic Children: A Guide for Autistic Wellbeing, Dr Luke Beardon

Understanding the sensing and perceptual world of autistic people is central to understanding autism.

“It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

it is so crucial that all environments to which your child has frequent access are assessed from a sensory perspective so that he has the least risk of anxiety. Very often within the sensory world, what seems so minor to others can be the key in terms of what is causing an issue for your child.

Avoiding Anxiety in Autistic Children: A Guide for Autistic Wellbeing, Dr Luke Beardon

All these examples show that sensory issues play a massive part in the day-to-day living experiences of your child. It is imperative that this is taken into account in as many environments as possible, in order that anxiety risk is minimized.

Avoiding Anxiety in Autistic Children: A Guide for Autistic Wellbeing, Dr Luke Beardon

Sensory needs are an absolute necessity to get right if your child is to feel comfortable (literally and figuratively) at school.

Avoiding Anxiety in Autistic Children: A Guide for Autistic Wellbeing, Dr Luke Beardon

Sensory pleasure (which could be viewed as almost the opposite feeling to anxiety) can be one of the richest, most delightful experiences known to the autistic population – and should be encouraged at any appropriate opportunity.

Avoiding Anxiety in Autistic Children: A Guide for Autistic Wellbeing, Dr Luke Beardon

Considering and meeting the sensory needs of autistic people in housing | Local Government Association

If we are serious about enabling thriving in autistic lives, we must be serious about the sensory needs of autistic people, in every setting. The benefits of this extend well beyond the autistic communities; what helps autistic people will often help everyone else as well.

Considering and meeting the sensory needs of autistic people in housing | Local Government Association

Finally, the involvement of autistic people in reviewing and changing the sensory environment will support the identification of things that are not visible or audible to their neurotypical counterparts. We strongly encourage this wherever possible.

Considering and meeting the sensory needs of autistic people in housing | Local Government Association

“Small changes that can easily be made to accommodate autism really do add up and can transform a young person’s experience of being in hospital. It really can make all the difference.”

“It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

This report introduces autism viewed as a sensory processing difference. It outlines some of the different sensory challenges commonly caused by physical environments and offers adjustments that would better meet sensory need in inpatient services.

“It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

We have five external senses and three internal senses. All must be processed at the same time and therefore add to the ‘sensory load’.

“It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

Autism is viewed as a sensory processing difference. Information from all of the senses can become overwhelming and can take more time to process. This can cause meltdown or shutdown.

“It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

ADHD (Kinetic Cognitive Style) is not a damaged or defective nervous system. It is a nervous system that works well using its own set of rules.

ADHD or what I prefer to call Kinetic Cognitive Style (KCS) is another good example. (Nick Walker coined this alternative term.) The name ADHD implies that Kinetics like me have a deficit of attention, which could be the case as seen from a certain perspective. On the other hand, a better, more invariantly consistent perspective is that Kinetics distribute their attention differently. New research seems to point out that KCS was present at least as far back as the days in which humans lived in hunter-gatherer societies. In a sense, being a Kinetic in the days that humans were nomads would have been a great advantage. As hunters they would have noticed any changes in their surroundings more easily, and they would have been more active and ready for the hunt. In modern society it is seen as a disorder, but this again is more of a value judgment than a scientific fact.

Bias: From Normalization to Neurodiversity – Neurodivergencia Latina

I’m not a fan of the “ADHD” label because it stands for “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder,” and the terms “deficit” and “disorder” absolutely reek of the pathology paradigm. I’ve frequently suggested replacing it with the term Kinetic Cognitive Style, or KCS; whether that particular suggestion ever catches on or not, I certainly hope that the ADHD label ends up getting replaced with something less pathologizing.

Toward a Neuroqueer Future: An Interview with Nick Walker | Autism in Adulthood

Almost every one of my patients wants to drop the term Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, because it describes the opposite of what they experience every moment of their lives. It is hard to call something a disorder when it imparts many positives. ADHD is not a damaged or defective nervous system. It is a nervous system that works well using its own set of rules.

Secrets of the ADHD Brain: Why we think, act, and feel the way we do.

First thing and this really is probably the most important thing that defines the syndrome is the cognitive component of ADHD: an interest-based nervous system.

So ADHD is a genetic neurological brain based difficulty with getting engaged as the situation demands.

People with ADHD are able to get engaged and have their performance, their mood, their energy level, determined by the momentary sense of four things:

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

- Interest (Fascination)

- Challenge or Competitiveness

- Novelty (Creativity)

- Urgency (Usually a deadline)

Glickman & Dodd (1998) found that adults with self-reported ADHD scored higher than other adults on self-reported ability to hyper-focus on “urgent tasks”, such as last-minute projects or preparations. Adults in the ADHD group were uniquely able to postpone eating, sleeping and other personal needs and stay absorbed in the “urgent task” for an extended time.

From an evolutionary viewpoint, “hyperfocus” was advantageous, conferring superb hunting skills and a prompt response to predators. Also, hominins have been hunter gatherers throughout 90% of human history from the beginning, before evolutionary changes, fire-making, and countless breakthroughs in stone-age societies.

Hunter versus farmer hypothesis – Wikipedia

The most important feature is that attention is not deficit, it is inconsistent.

“Look back over your entire life; if you have been able to get engaged and stay engaged with literally any task of your life, have you ever found something you couldn’t do?”

A person with ADHD will answer, “No. If I can get started and stay in the flow, I can do anything.

Omnipotential

People with ADHD are omnipotential. It’s not an exaggeration, it’s true. They really can do anything.

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

People with ADHD live right now.

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

- Performance is usually the only aspect that most people look for.

- Boredom and lack of engagement is almost physically painful to people with an ADHD nervous system.

- When bored, ADHDers are irritable, negativistic, tense,

argumentative, and have no energy to do anything.- ADDers will do almost anything to relieve this dysphoria. Self-medication. Stimulus seeking. “Pick a fight.”

- When engaged, ADHDers are instantly energetic, positive, and social.

- This shifting of mood and energy is often misinterpreted as Bipolar Disorder.

People with ADHD do not fit in any school system.

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

People with ADHD live right now. They have to be personally interested, challenged, and find it novel or urgent right now, this instant, or nothing happens because they can’t get engaged with the task.

Passion. What is it about your life that gives your life meaning purpose? What is it that you’re eager to get up and go do in the morning? Unfortunately, only about one in four people ever discover what that is, but it is probably the most reliable way of staying in the zone that we know of.

Defining Features of ADHD That Everyone Overlooks: RSD, Hyperarousal, More (w/ Dr. William Dodson)

People who have ADHD nervous systems lead intense passionate lives. Their highs are higher, their lows are lower, all of their emotions are much more intense.

An ADHD Guide to Emotional Dysregulation and Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (w/ William Dodson, M.D.)

At all points in the life cycle, people who have an ADHD nervous system lead intense, passionate lives.

They feel more in every way than do Neurotypicals.

Consequently, everyone with ADHD but especially children are always at risk of being overwhelmed from within.

Rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD) is extreme emotional sensitivity and pain triggered by the perception that a person has been rejected or criticized by important people in their life. It may also be triggered by a sense of falling short—failing to meet their own high standards or others’ expectations.

How ADHD Ignites Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

We have a couple of theme songs for KCS/DREAD/ADHD in our community: Guided by Angels by Amyl and the Sniffers and Monkey Mind by The Bobby Lees.

Guided by angels But they're not heavenly They're on my body And they guide me heavenly The angels guide me heavenly, heavenly Energy, good energy and bad energy I've got plenty of energy It's my currency I spend, protect my energy, currency Guided by Angels by Amyl and the Sniffers

Monkey Mind

It's just my monkey mind

Monkey Mind

It's just my

I take him out, and then I sit him down

I look him in the eye, and say no more

monkeying around

Now you look-y here, you gonna leave me

alone

Cause there's no room here for a little

monkey in my home

Monkey Mind

It's just my monkey mind

Monkey Mind

It's just my

That monkey mind, he likes to eat himself alive

Think he's done, and then he takes another bite

Now see, I gotta learn to be kind

To my monkey mind, cause he'll be with me till I die

Monkey Mind

It's just my monkey mind

Monkey just my

Monkey Mind by The Bobby Lees

The ADHD Nervous System: An explanation of why we act the way we do.

Redefining Autism Science with Monotropism and the Double Empathy Problem

If we are right, then monotropism is one of the key ideas required for making sense of autism, along with the double empathy problem and neurodiversity. Monotropism makes sense of many autistic experiences at the individual level. The double empathy problem explains the misunderstandings that occur between people who process the world differently, often mistaken for a lack of empathy on the autistic side. Neurodiversity describes the place of autistic people and other ‘neurominorities’ in society.

Monotropism – Welcome

Monotropism and the Double Empathy Problem are two of the biggest and most important things to happen to autism research. In the previous two issues of the Guide to the NeurodiVerse, “From an Ivory Tower Built on Sand to Open, Participatory, Emancipatory, Activist Research” and “Mental Health and Epistemic Justice“, we tackled some bad trends in autism science. Here, we celebrate two trends that get it right.

Monotropism is a theory of autism developed by autistic people, initially by Dinah Murray and Wenn Lawson.

Welcome – Monotropism

Monotropic minds tend to have their attention pulled more strongly towards a smaller number of interests at any given time, leaving fewer resources for other processes. We argue that this can explain nearly all of the features commonly associated with autism, directly or indirectly. However, you do not need to accept it as a general theory of autism in order for it to be a useful description of common autistic experiences and how to work with them.

The ‘double empathy problem’: Ten years on – Damian Milton, Emine Gurbuz, Betriz Lopez, 2022

These two videos, totaling less than 10 minutes, are wonderful ways to get in touch with modern autism science.

Understanding monotropism and the double empathy problem will help you get things right, instead of wrong, when interacting with autistic people.

If an autistic person is pulled out of monotropic flow too quickly, it causes our sensory systems to disregulate.

This in turn triggers us into emotional dysregulation, and we quickly find ourselves in a state ranging from uncomfortable, to grumpy, to angry, or even triggered into a meltdown or a shutdown.

This reaction is also often classed as challenging behavior when really it is an expression of distress caused by the behavior of those around us.

How you can get things wrong:

An introduction to monotropism – YouTube

- Not preparing for transition

- Too many instructions

- Speaking too quickly

- Not allowing processing time

- Using demanding language

- Using rewards or punishments

- Poor sensory environments

- Poor communication environments

- Making assumptions

- A lack of insightful and informed staff reflection

Image license: CC-By Attribution 4.0 International

Image source: What is Neurodiversity? – Genius Within

Via: Point of View: An annotated introductory reading list for neurodiversity | eLife

An education that is designed to the edges and takes into account the jagged learning profile of all students can help unlock the potential in every child.

From Hostility to Community – Teachers Going Gradeless

Me and you and our diagnoses

A perfect match in a bag of explosives

Catch of the day in a toxic ocean

Nothing wrong with us, it's the world that's broken

Two tokens short of the rollercoaster

Ancient conditions

With brand new solutions

In the old days they'd be doing ablutions

I'd be a prophet and you'd be a seer

Or you'd be a healer, I'd be a freak

Run away with the circus

Then we'd meet after work for a barrel of beer, yeah

Me and you and our diagnoses

All cosied up but it's hard to focus

Me and you and our trauma flashbacks

Relaxing at home with a hornet's backpack

Stuffed full of my dysphoria

Your dyspraxia, off exploring

Panic attacks to get the heart rate up

Good cardio-vascular, will get back to ya afterwards

Short psychotic episode

If I even leave the house I'll forget to close the door

I'll forget what I went out for

And come back with a random object or four

Quetiapine, lamotrigine, fluoxetine

You'll wash it down with Listerine

I've never felt so at home

Since methylphenidate and testosterone

C-PTSD, ADHD, OCD and PMDD

Anxious attachment, TBI

But it's the world that's sick, baby, we're alright

C-PTSD, ADHD, anxiety

Bipolar, addiction, neurodivergence

I'd be more worried if we weren't disturbed

We got our own alphabet

Big bunch of letters between you and I

It's the right response to a world gone wrong

And we're getting on just fine

Me and you and our diagnoses

Out for a wander with coffee and oatmilk

The posher the roastery, the more you want it

Cause you came from nothing

And you're out for the summit

So we go hard but it's softly, softly

And we're so scarred but it's not a problem

There's a lot of good reasons to stop what we're doing

But my disassociation means I've forgotten, hah

I'm overwhelmed and over diagnosed

And overexposed, I suppose

With all these letters we're dragging around

It's lucky I turned that MBE down

We just take it day by day

Staying doesn't mean you never want to run away

It means you weather it

Whether it's pleasure every minute

Or a bit of hard graft, grin hold fast

C-PTSD, ADHD, OCD and PMDD

Anxious attachment, TBI

It's the world that's sick, baby, we're alright

C-PTSD, ADHD, anxiety

Bipolar, addiction, neurodivergence

I'd be more worried if we weren't disturbed

Kae Tempest – Diagnoses Lyrics

Join us in affirming our ways of being.

Back Off

I want to talk about the potential benefits of less therapies. I want to talk about eliminating interventions. I want to talk about why what is called “prompting” is actually forcing and how that should be stopped.

Basically, I want to make the case for backing the eff off Autistic kids–Autistic people in general, actually.

All I’m asking for is a SINGLE study that provides any evidence that ABA is any more effective than kids spending equivalent time with someone who knows nothing about ABA.

If they can’t show that, how on Earth do they think they can justify a multi-billion dollar industry? What?

Pretty much everything an autistic child does, says, doesn’t do or doesn’t say is pathologised and made into a way to invent a ‘therapy’ for it.

It’s actually _hell_ to experience.

We should stop doing this and start learning about autism.

The Basics of Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

- Presume Competence — Presuming competence means assuming an individual can learn, think, and understand, even when we may not have evidence available to confirm this.

- Promote Autonomy — When we promote autonomy with children and young people, we are giving them the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and supporting them to have a voice in all aspects of their lives.

- Respect all Communication Styles — To be neurodiversity affirming regarding communication, we need to consider all communication as valid and acknowledge that there are many ways that individuals communicate beyond spoken language.

- Be Informed by Neurodivergent Voices — Evidence-based practice incorporates research, clinical knowledge and expert opinion, along with client preferences, to provide effective support, and who better to provide expert opinion than neurodivergent individuals themselves.

- Take a Strengths-Based Approach — A strengths-based approach not only considers an individual’s personal strengths, but also how conditions in their environment can be adapted to remove barriers and facilitate access to desired activities.

- Honor Neurodivergent Culture — As therapists, we can honor our client’s neurodivergence by giving them a safe space to be themselves, accommodating their needs and being accepting of their neurodivergent style of being.

- Tailor Support to Individual Needs — Tailoring an approach specifically to a client’s needs involves recognising that due to differences in sensory processing, cognition, communication, and perception, neurodivergent individuals experience the world differently to the neurotypical population, and as such are likely to need different therapeutic supports.

The 5 As of Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

- Authenticity – A feeling of being your genuine self. Being able to act in a way that feels comfortable and happy for you.

- Acceptance – A process whereby you feel validated as the person you are, not only by yourself but by others too.

- Agency – A feeling of control over actions and their consequences in your day-to-day life.

- Autonomy – A state of being self-directed, independent, and free. Being able to act on your ideas and wants.

- Advocacy – To speak for yourself, communicate what is important to you and your needs or the needs of others.

The 6 Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Practice

- Safety: Prioritising the physical, psychological and emotional safety of young people.

- Trustworthiness: Explaining what we do and why, doing what we say we will do, expectations being clear and not overpromising.

- Choice: Young people are supported to be shared decision makers and we actively listen to the needs and wishes of young people.

- Collaboration: The value of young people’s experience is recognised through actively working alongside them and actively involving young people in the delivery of services.

- Empowerment: We share power as much as we can, to give young people the strongest possible voice.

- Cultural consideration: We actively aim to move past cultural stereotypes and biases based on, for example, gender, sexual orientation, age, religion, disability, geography, race or ethnicity.

The NEST Approach for Supporting Young People in Distress

- Nurture — The very first thing we need to remember is to help a young person feel safe – remember that experiencing a meltdown is incredibly scary. If someone is upset/ stressed/ having a meltdown, focusing on helping them to feel calm is important as people cannot think logically at this time. Until they feel safe, there is no next productive step.

- Empathise — If someone is struggling or has reached crisis point, it is important to assume there is a good reason why and to try to understand their perspective, plus any reasoning for their current struggle.

- Sharing Context — Why do we want to problem solve with the young person? We need to show that how the young person feels is important to us, but also share the perspectives of other people so they can fully understand the situation if the situation is a result of miscommunication.

- Teamwork — Most services and settings focus on a system of rewards and punishments for changing behaviour. We understand that when young people are struggling we need to address the root cause. The best way to do this is by working together.

Source: The NEST Approach for Supporting Young People in Distress

Understanding Motivation and Behaviour through Self-Determination Theory

- Autonomy — Self-Determination Theory (SDT) underscores the importance of autonomy in motivation and behaviour. Autistic young people are more likely to engage positively when they have choices and control over their actions. Our school environment is designed to provide opportunities for autonomy, such as choosing activities and setting goals.

- Competence — Competence is another key component of SDT. We recognize the importance of providing opportunities for young people to develop and showcase their skills and abilities. This fosters a sense of competence and achievement. We take an asset-based approach: identifying key strengths that our pupils have and fostering these strengths rather than solely focusing on their challenges. As a result, pupils feel empowered to further develop their own skill sets and recognise their unique contributions.

- Relatedness — Relatedness, the third component of SDT, emphasises the significance of positive social connections. Our school promotes acceptance, teamwork, and relationship-building among participants, creating a sense of belonging and relatedness.

- Integration with Our Principles — The principles of SDT are integrated into our behaviour management approach. By supporting autonomy, competence, and relatedness, we enhance motivation, engagement, and overall wellbeing of our students.

Source: Understanding Motivation and Behaviour through Self-Determination Theory

Key Principles When Supporting Autistic People

- Autism Acceptance — In many spaces and places autism is seen as a negative thing. Autism is not a ‘disorder’ or a ‘burden’, it is simply a difference. Just like every other brain type, the autistic brain has its negatives and its positives.

- Young people often need to recover from their negative experiences to be able to thrive — Young people need time, and the right support to recover. Especially since outside of safe spaces, they may still be exposed daily to trauma and stress.

- Young people do well if they can — We believe that all young people do well if they can. Everyone wants to thrive, do well, and no one wants to cause upset with others or break rules. If someone is struggling – there is a reason why they are struggling. We can work together to identify reasons why and what may help.

- Co-regulation — Young people need repeated experiences of co-regulation from a regulated adult before they can begin to self-regulate. They may also not know how to regulate by themselves and we may be a key resource to help them create ways that work for them.

- Self-Care — Self care is vital – it isn’t possible to properly care for young people when you are overwhelmed yourself.

- Neurodiversity affirming practice — We believe in the 5 As of neurodiversity affirming practice, from The Autistic Advocate. This is a strengths and rights-based approach to affirm a young person’s identity, rather than focusing on ‘fixing’ a young person because of their neurotype.

Top 5 Neurodivergent-Informed Strategies

- Be Kind — Take time to listen and be with people in meaningful ways to help bridge the Double Empathy Problem (Milton, 2012). Be embodied and listen not only to people’s words but also to their bodies and sensory systems.

- Be Curious — Be informed by the voices of those with lived experience, learn from and act on the neurodiversity-affirming research that is evolving and that validates the inner experiences of neurodivergent people. For Autistic/ ADHD people, this includes understanding how the theory of monotropism and embracing people’s natural flow state can support well-being (Murray et al., 2005) and (Heasman et al., 2024).

- Be Open — Be open and be compassionate. It has been shown that neurodivergent people are at a higher risk of mental difficulties and suicide (Moseley, 2023). Think about the weight a neurodivergent person carries in a society that values neuronormative ways of being and consider the impact of masking on people’s mental health (Pearson and Rose, 2023).

- Be Radically Inclusive — We need a strength-based approach to care and education. (Laube 2023) suggested we must acknowledge and respect a person’s neurodivergence, learn how it affects them, and value their unique experiences. We need individualised support instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach. We should try to reduce and challenge stigma and stereotypes and provide radically inclusive spaces for people to thrive in.

- Be Neurodiversity-Affirming — Take time to read about the neurodiversity paradigm “Neurodiversity itself is just biological fact!” (Walker, 2021); a person is neurodivergent if they diverge from the dominant norms of society. “The Neurodiversity Paradigm is a perspective that understands, accepts and embraces everyone’s differences. Within this theory, it is believed there is no single ‘right’ or ‘normal’ neurotype, just as there is no single right or normal gender or race. It rejects the medical model of seeing differences as deficits.” (Edgar, 2023)

Autistic SPACE: A Novel Framework for Meeting the Needs of Autistic People

- Sensory needs — Autistic people experience the world differently (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). Sensory sensitivities are common to almost all autistic people (MacLennan et al, 2022), but the pattern of sensitivities varies (Lyons-Warren and Wan, 2021). Autistic people can be sensory avoidant, sensory seeking or both (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020); hypo- or hyper-reactivity to any sensory modality is possible (Tavassoli et al, 2014) and a person’s sensory responsiveness can vary depending on circumstances (Strömberg et al, 2022). A ‘sensory diet’ provides scheduled sensory input which can aid physical and emotional regulation (Hazen et al, 2014).

- Predictability — Autistic people need predictability and may experience extreme anxiety with unexpected change (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). This underlies the autistic preference for routine and structure.

- Acceptance — Beyond simple awareness, there is a pressing need for autism acceptance. A neurodiversity-affirmative approach recognises that neurodevelopmental differences are part of the natural range of human development (Shaw et al, 2021) and acknowledges that attempts to make autistic people appear non-autistic can be deeply harmful (Bernard et al, 2022). This does not exclude inherent or environmental disability.

- Communication — Autistic people communicate differently. Many use fluent speech, but may experience challenges with verbal communication at times of stress or sensory overload (Cummins et al, 2020; Haydon et al, 2021). Others do not speak or may use few words (Brignell et al, 2018). Many non-speaking or minimally speaking autistic people use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods, including visual cards, writing or electronic devices, which should be facilitated (Zisk and Dalton, 2019).

- Empathy — Despite common assumptions to the contrary, autistic people do not lack empathy (Fletcher-Watson and Bird, 2020). It may be experienced or expressed differently, but this is perhaps the most damaging misconception about autism (Hume and Burgess, 2021). In fact, many autistic people report experiencing hyper-empathy, to the point of being unable to deal with the onslaught of emotions, leading to ‘shutdown’ in order to cope (Hume and Burgess, 2021). A bi-directional, mutual misunderstanding occurs between autistic and non-autistic people, termed ‘the double empathy problem’ (Milton, 2012). As such, non-autistic healthcare providers may struggle to empathise with autistic patients, particularly where communication training is generally conducted from a neuronormative, non-autistic perspective, in which the needs of autistic people are not considered (Bradshaw et al, 2021).

Source: Autistic SPACE: A Novel Framework for Meeting the Needs of Autistic People

NEST (NEurodivergent peer Support Toolkit)

- Inclusivity. The NEST group is a club for all neurodivergent young people, whether they have a formal diagnosis or not. NEST groups should also be thinking about other forms of inclusivity – for example making sure that any students who might feel marginalised in other ways (e.g. being from a minority ethnicity or sexuality group, or having a physical disability) are welcomed to the group.

- Belonging. Peer support allows neurodivergent young people to support each other through their shared understanding. Through NEST groups, we envisage opportunities for neurodivergent young people to share stories and strategies that help them flourish, to feel welcomed ‘as they are’, and to be part of the school community.

- Acceptance. When people feel accepted, they can relax, be frank about their troubles without fear of judgement, and enjoy themselves. Students attending a NEST group should be supported to accept each other, and themselves. This may also lead to greater participation in school life, leadership in the community, and wellbeing.

- Advocacy. Getting support from other people can help make sure neurodivergent young people’s voices are heard on issues that are important to them, that their rights are protected and promoted, and that their views and wishes are genuinely considered when decisions are being made about their lives. NEST groups aim to help neurodivergent students advocate for each other, and for themselves.

The Eight Dimensions of Care

- Insiderness/Objectification

- “…insiderness recognizes that we each have a personal world that carries a sense of how things are for us. Only the individual themself can be the authority on how this inward sense is for them.”

- “Objectification treats someone as lacking in subjectivity, or as a tool or object lacking agency…”

- “Objectification denies the inner subjectivity of a child or young person, removing their full humanness or agency, while treating their inner world as thin or non-existent.”

- Agency/Passivity

- “Being human involves being able to make choices and to be generally held accountable for one’s actions. Having a sense of agency is closely linked to a sense of dignity.”

- Uniqueness/Homogenization

- “To be human is to actualize a self that is unique.”

- “Each person’s uniqueness is a product of their relationships and their context.”

- “Recognizing the child and young person’s characteristics, attributes, and roles (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, class, friend, son, and student) honors and supports them in their journey toward a flourishing life and is essential for well-being.”

- “Homogenization erodes identity by focusing on conformity and norming.”

- Togetherness/Isolation

- “A person’s uniqueness exists in relation to others and in community with others.”

- “Through relationships, practitioners and the children and young people they work with have the opportunity to learn more about themselves, through both commonalities and differences.”

- “Inclusive practices nurture a sense of belonging and connection.”

- “Togetherness is experienced through building bridges of understanding and empathy to validate the young person’s suffering, struggles, strengths, and perspectives.”

- Sense-Making/Loss of Meaning

- “Sense-making involves a motivation to find meaning and significance in things, places, events, and experiences.”

- “The child or young person is viewed as the nascent storyteller and storymaker of their own life.”

- “Autistic ways of being and perceiving are understood as intrinsically meaningful and help formulate a view of the young person’s lifeworld, their health, well-being, and identity.”

- “Listening openly to autistic interpretations of experiences in a relational way supports the young person to make sense of their world so they can define their experiences and reflect on how these experiences have shaped them.”

- Personal Journey/Loss of Personal Journey

- “To be human is to be on a journey.”

- “Understanding how we are at any moment requires the context of the past, present, and future, and ways of bringing each of these parts together into a coherent or appreciable narrative.”

- “A child or young person can and should be able to simultaneously feel secure in connections to the past while moving into the unfamiliarity and uncertainty of the future.”

- Sense of Place/Dislocation

- “To feel “at home” is not just about coming from a physical place, it is where the young person finds meaning and feels welcome, safe, and connected.”

- “Security, comfort, familiarity, and continuity are important factors in creating a sense of place.”

- “Dislocation is experienced when the child or young person is in an unfamiliar, unknown culture where the norms and routines are alien to them.”

- “The space, policies, or conventions do not reflect their identity or needs.”

- Embodiment/Reductionist View of the Body

- “Being human means living within the limits of our human body.”

- “Embodiment relates to how we experience the world, and this includes our perceptions of our context and its possibilities, or limits.”

- “A child or young person’s experience of the world is influenced by the body’s experience of being in the world, feeling joy, playfulness, excitement, pain, illness, and loss of function.”

- “Embodiment views well-being as a positive quality while also acknowledging struggles and the complexities of living.”

Good Autism Practice

- Understanding the Individual

- Principle One: Understanding the strengths, interests, and needs of each autistic child.

- Principle Two: Enabling the autistic child to contribute to and influence decisions.

- Positive and Effective Relationships

- Principle Three: Collaboration with parents/carers and other professionals and services.

- Principle Four: Workforce development related to good autism practice.

- Enabling Environments

- Principle Five: Leadership and management that promotes and embeds good autism practice.

- Principle Six: An ethos and environment that fosters social inclusion for autistic children.

- Learning and Development

- Principle Seven: Targeted support and measuring the progress of autistic children.

- Principle Eight: Adapting the curriculum, teaching, and learning to promote wellbeing and success for autistic children.

Source: Good Autism Practice Guidance | Autism Education Trust

It’s Not Rocket Science: 10 Steps to Creating a Neurodiverse Inclusive Environment

- Adapt the Environment

- The sensory environment – Does the individual have a place to work where they feel comfortable? Are the ambient sounds, smells, and visuals tolerable? Is the lighting suitable? What about uncomfortable tactile stimuli? Has room layout been considered? Can ear defenders, computer screen filters or room dividers be used to create a more comfortable work environment? Do people working with them have information about what might be a problem – e.g. strong perfume – and do they understand why this matters?

- The timely environment – Has appropriate time been allowed for tasks? Allowing time to reflect upon tasks and address them accordingly will maximise success. Are time scales realistic? Have they been discussed? Are there explicit procedures if tasks are finished early or require additional time? Are requests to do things quickly kept to a minimum with the option to opt out of having to respond rapidly?

- The explicit environment – Is everything required made explicit? Are some tasks based upon implicit understanding which draw upon social norms or typical expectations? Is it clear which tasks should be prioritised over others? Avoid being patronising but checking that everything has been made explicit will reduce confusion later. Is there an explicit procedure for asking questions should they arise (e.g. a named person (a mentor) to ask in the first instance)?

- The predictable environment – How predictable is the environment? Is it possible to maximise predictability? Uncertainty can be anxiety provoking and a predictable environment can help in reducing this and enable greater task focus. Can regular meetings be set up? Is it possible that meetings may have to be cancelled in the future? Are procedures clear for when expected events (such as meetings) are cancelled, with a rationale for any alterations? Can resources and materials be sent in advance?

- The social environment – Are procedures clear for when expected events (such as meetings) are cancelled, with a rationale for any alterations? Can resources and materials be sent in advance?

- Support the Individual