The tight connection between thinking and moving is a legacy of our species’s evolutionary history.

The Extended Mind – Annie Murphy Paul

We inherited a “mind on the hoof,” in the phrase of philosopher Andy Clark—but in today’s classrooms and offices, the vigorous clatter of hoofs has come to an eerie halt.

The Extended Mind – Annie Murphy Paul

What this attitude overlooks is that the capacity to regulate our attention and our behavior is a limited resource, and some of it is used up by suppressing the very natural urge to move.

The suppression of our need to fidget, stim, and move results in the exclusion of neurodivergent people from school. We have turned classrooms into a hell for neurodivergence. Suppressing fidgeting contributes to that.

Within the constant overwhelm is a pilot flame of anxiety, burning always. Anxiety and overwhelm, the torrid pas de deux that belies the silent, almost still compliance. Their dance is steam and froth, resonance foam on the sensory ocean I swim beneath the almost stillness – still but for the tugging of my hair. Don’t disallow me that, but some of them will. Fidgeting is a threat.

CHAMPS and the Compliance Classroom – Stimpunks Foundation

Offer bodymind affirmations and provide outlets for stimming, pacing, fidgeting, and retreating. At Stimpunks, we use this bodymind affirmation before all meetings/gatherings:

“We should all move in our space in whatever way is most comfortable for our bodyminds. Please use this space as you need or prefer. Sit in chairs or on the floor, pace, lie on the floor, rock, flap, spin, move around, come in and out of the room. This is an invitation for you to consider what your bodymind needs to be as comfortable as possible in this moment. This is an invitation to remind yourself to remember and to affirm that your bodymind has needs and that those needs deserve to be met, that your bodymind is valuable and worthy, that you deserve to be here, to belong.”

Lydia X. Z. Brown

We like to share the video “Walk In My Shoes” for a taste of what life is like for a hypersensory autistic person in school.

CYP = Children and Young People

Fidgeting and doodling can help with sensory overwhelm. It can help autistic CYPs filter and find a focus. This supports thinking and learning.

Lisa Chapman @CommonSenseSLT

Fidgeting and doodling help if you are feeling overwhelmed by providing rhythmical proprioceptive, tactile and visual input. They are forms of stimming. Stimming can be joyful as well as for regulation.

Lisa Chapman @CommonSenseSLT

Stimming can also provide controllable and rhythmical sound input. Stimming is a great way to regulate & can be a great tool for teachers to recognise & use to support #ActuallyAutistic CYPs

Lisa Chapman @CommonSenseSLT

The physical & emotional effects of having to work hard to filter, keep focussed, use additional sensory supportive strategies all day long, just to keep up with everyone else are ENORMOUS.

Lisa Chapman @CommonSenseSLT

School is child prison. It’s forcing kids to spend their childhood – a happy time! a time of natural curiosity and exploration and wonder – sitting in un-air-conditioned blocky buildings, cramped into identical desks, listening to someone drone on about the difference between alliteration and assonance, desperate to even be able to fidget but knowing that if they do their teacher will yell at them, and maybe they’ll get a detention that extends their sentence even longer without parole.

Book Review: The Cult Of Smart – by Scott Alexander

Table of Contents

- We’re Tired of “Quiet Hands!”

- We’re Tired of “Cop Shit”

- Activity-Permissive Settings

- Regulatory and Adaptive Roles of Fidgeting

- Acceptance and Sensory-Based Approaches

- Make Peace with Fidgeting: Think of It as Brain Development, Which It Is.

- Fidgeting, Monotropism, and Flow

- The Calm Joy of Engaging with Preferred Items

- Autistic Movement

- Conflicting Needs

- Freedom of Embodiment

- Further Reading

We’re Tired of “Quiet Hands!”

Autistic people (and others with developmental disabilities) have been fighting a war for decades. It’s a war against being forcibly, often brutally, conditioned to behave more like neurotypicals, no matter the cost to our own comfort, safety, and sanity. And those of us who need to stim in order to concentrate (usually by performing small, repetitive behaviors like, oh I don’t know, spinning something) have endured decades of “Quiet Hands” protocols, of being sent to the principal’s office for fidgeting, of being told “put that down/stop that and pay attention!,” when we are in fact doing the very thing that allows us to pay attention instead of being horribly distracted by a million other discomforts such as buzzing lights and scratchy clothing. We’ve had our hands slapped and our comfort objects confiscated. We’ve been made to sit on our hands. We’ve been tied down. Yes, disabled children get restrained—physically restrained—in classrooms and therapy sessions and many other settings, for doing something that has now become a massive fad.

What the Fidget Spinners Fad Reveals About Disability Discrimination — THINKING PERSON’S GUIDE TO AUTISM

In a classroom of language-impaired kids, the most common phrase is a metaphor.

“Quiet hands!”

A student pushes at a piece of paper, flaps their hands, stacks their fingers against their palm, pokes at a pencil, rubs their palms through their hair. It’s silent, until:

“Quiet hands!”

I’ve yet to meet a student who didn’t instinctively know to pull back and put their hands in their lap at this order. Thanks to applied behavioral analysis, each student learned this phrase in preschool at the latest, hands slapped down and held to a table or at their sides for a count of three until they learned to restrain themselves at the words.

The literal meaning of the words is irrelevant when you’re being abused.

We’re Tired of “Cop Shit”

The contemporary classroom is a bastion of neuronormativity. “Cop Shit” is abundant and on trend. The fight for the right to learn differently is a continuous confrontation with authoritarians with bad framing.

So why do we have cop shit in our classrooms?

One provisional answer is that the people who sell cop shit are very good at selling cop shit, whether that cop shit takes the form of a learning management system or a new pedagogical technique. Like any product, cop shit claims to solve a problem. We might express that problem like this: the work of managing a classroom, at all its levels, is increasingly complex and fraught, full of poorly defined standards, distractions to our students’ attentions, and new opportunities for grift. Cop shit, so cop shit argues, solves these problems by bringing order to the classroom. Cop shit defines parameters. Cop shit ensures compliance. Cop shit gives students and teachers alike instant feedback in the form of legible metrics.

In short, cop shit operates according the the logic of datafication. Indeed, the rise of ed tech has seen the multiplication and proliferation of unprecedented forms of cop shit. See, for instance, this illuminating post on the “The 100 Worst Ed-Tech Debacles of the Decade,” published at the end of last year. It’s a murderer’s row of cop shit.

Cop shit is seductive. It makes metrics transparent. It allows for the clear progress toward learning objectives. (“Badges” are cop shit, by the way.) It also subsumes education within a market logic. “Here,” cop shit says, “you will learn how to do this thing. We will know you learned it by the acquisition of this gold star. But in order for me to award you this gold star, I must parse you, sense you, track you, collect you, and—” here’s the key, “I will presume that you will attempt to flout me at every turn. We are both scamming each other, you and I, and I intend to win.” When a classroom becomes adversarial, of course, as cop shit presumes, then there must be a clear winner and loser. The student’s education then becomes not a victory for their own self-improvement or -enrichment, but rather that the teacher conquered the student’s presumed inherent laziness, shiftiness, etc. to instill some kernel of a lesson.

Against Cop Shit | Jeffrey Moro

What Makes a Good Teacher?

| Student | Study | Sensory difference identified | Facilitating Strategies | Barriers |

| Benton | 1 | High levels of auditory stimulation and physical movement | Fidget tools; being allowed to stand up and spin; learning through discussion | Silent working; exam conditions; being told off for fidgeting |

| Daz | 1 | High levels of somatosensory stimulation | Chewing gum to concentrate; biting pens; being allowed to move in seat | Having chewing gum confiscated and then being told off for chewing on shirt collar; being told to sit still |

| Jeffrey | 1 | High levels of personal space and regulation of temperature | Being allowed to sit near a window for ventilation; being allowed to remove blazer/jumper | Seating plans where placement was next to a student that ‘spread out’ their belongings |

| Lewis | 1 | Low levels of auditory stimulation; high levels of personal space | Individual working; quiet lessons; being allowed to take ‘time out’ in the classroom | Enforced group work; noisy, moving classes (e.g. PE, DT) without a quiet space |

| Matthew | 1 | Low levels of olfactory stimulation (made nauseous by certain smells) | Being allowed to spend wet breaks in classrooms rather than the canteen; being allowed to sit near a window and open it to breathe fresh air | Being told off for sniffing certain fabrics for comfort; being told off for ‘overreacting’ to certain smells |

| Stanley | 1 | High levels of visual stimulation; low levels of auditory stimulation | Visual rather than verbal prompts; being allowed to listen to music to concentrate | Being told off for getting distracted by new environments |

| Yazi | 2 | Low levels of auditory stimulation; high levels of physical movement | Being allowed to fidget and doodle while listening to instructions | Being told off for reading a book rather than talking to peers |

| Sage | 2 | Low levels of both auditory and visual stimulation | 1-2-1 instruction and prompting; pair rather than group work | Being told off/punished for ‘withdrawing’ when overloaded and doing no work |

| Genji | 2 | High levels of both auditory and visual stimulation | ‘Banter’ and individual conversations with a teacher; typing on an iPad rather than writing | Silent working; lack of visual schedule to refer to when distracted |

| Hanzo | 2 | High levels of both auditory stimulation and physical movement | Energetic and noisy tasks; large group work; being allowed to use fidget toy | Silent working; being told off for fidgeting; working with unfamiliar students |

| Bob | 2 | Low levels of both auditory and visual stimulation | Whole class instruction; being ‘leader’ in a group; pair work | Working with unfamiliar students |

| Jack | 2 | High levels of both auditory and visual stimulation | Colour-coding to keep subjects organised; using interests for projects (e.g. creative writing essay) | Being told off for inappropriate affect; instructions not given face to face (e.g. shouted across the room) |

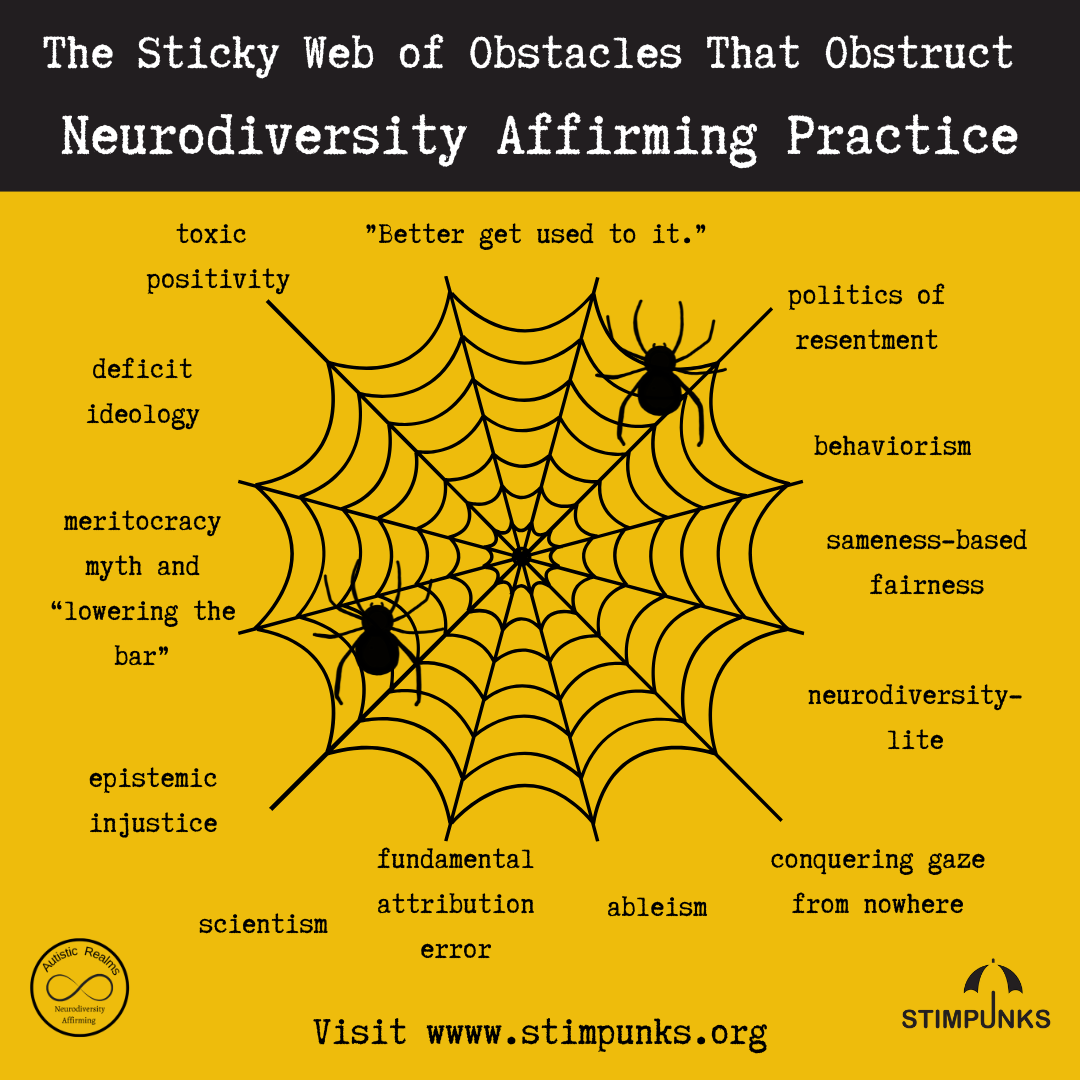

When our community advocates for neurodiversity-affirming practices instead of more cop shit, we meet these obstacles.

Obstacles to DEI-AB and Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

(links are to our glossary, where you can learn much more)

- politics of resentment

- sameness-based fairness

- fundamental attribution error

- conquering gaze from nowhere

- toxic positivity

- neurodiversity-lite

- scientism

- epistemic injustice

- behaviorism

- ableism

- deficit ideology

- ”Better get used to it.”

- meritocracy myth

- “lowering the bar”

politics of resentment = manipulations of status anxiety; organization of interest groups based on perceived deprivation or the threat of deprivation

sameness-based fairness = notion of fairness where everyone gets the same thing rather than each getting what they need

fundamental attribution error = to underestimate the impact of situational factors and to overestimate the role of dispositional factors in controlling behaviour

conquering gaze from nowhere = the interpretation of objectivity as neutral and not allowing for participation or stances; an uninvolved, uninvested approach that claims objectivity to “represent while escaping representation”

toxic positivity = belief that success happens to good people and failure is just a consequence of a bad attitude rather than structural conditions

neurodiversity-lite = using neurodiversity as a buzzword; a way to profit from the appropriation of a human rights movement; a cottage industry for therapists, clinics, and companies to sell their associated products, classes, books, and training to the public without having a clue about neurodiversity

scientism = the belief that science is the only route to useful knowledge

epistemic injustice = where our status as knowers, interpreters, and providers of information, is unduly diminished or stifled in a way that undermines the agent’s agency and dignity

behaviorism = a dehumanizing mechanism of learning that reduces human beings to simple inputs and outputs

ableism = a system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness

deficit ideology = a worldview that explains and justifies outcome inequalities by pointing to supposed deficiencies within disenfranchised individuals and communities

better get used to it = preparing people for oppression by oppressing them

meritocracy myth = a widely held but false assertion that individual merit is always rewarded; the myth of meritocracy is one of the longest lasting and most dangerous falsehoods in American life

lowering the bar = a racist, sexist, and ableist narrative with no basis in reality that represents diversifying hiring pipelines, attracting candidates from underrepresented groups, and supporting them in the workplace as “lowering the bar” by hiring less-qualified individuals

“Ed bro rationalists” confront us with studies framed in scientism and epistemic injustice that are abused to justify abusing us and further suppressing us.

You can’t reduce the complexity of learning and our lived experience to studies that measure the surface, badly. We’re raising whole children, not frankenstein children.

Don’t be an ed bro.

Don’t be a cop.

Be a teacher.

Anyone trying to police other people’s self-identities is just another tedious cop, and a cop is pretty much the most un-queer, non-liberatory thing a person can be.

Walker, Nick. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities (pp. 166-167). Autonomous Press.

Simon Says: Be Still

Simon says smile.

Show us your teeth.

You’re only as valuable as you are able.

Simon says it's not time for a bathroom break.

You go when Simon says.

Simon says you're not listening.

People that don’t listen will never be successful.

Simon Says speak only when you are told to speak.

Simon says it’s still not time for a bathroom break and stop asking.

Simon says it's time to file in the hallways now

one behind

the other

straight side of the line

tight to the right

Simon Says that you if can't be silent

how will you hear what Simon is telling you to do.

Silence!

I said be silent.

Simon says be silent.

Simon says

if you can't handle this classroom

how will you handle your jail cell

So sit up straight and

Be Still

Be Still

Be Still

A Fade to Extinction for Ethically Questionable Approaches That Disregard Neurodiversity

- CHAMPS and the Compliance Classroom – Stimpunks Foundation

- Eye Contact and Neurodiversity – Stimpunks Foundation

- Education Access: We’ve Turned Classrooms Into a Hell for Neurodivergence – Stimpunks Foundation

- Behaviorism – Stimpunks Foundation

- Does Behaviorism Belong in the Classroom? – Stimpunks Foundation

- There Is Little Empirical Basis to Suggest That PBS Is Effective – Stimpunks Foundation

- A Fade to Extinction for Ethically Questionable Approaches That Disregard Neurodiversity – Stimpunks Foundation

- DIY at the Edges: Surviving the Bipartisanship of Behaviorism by Rolling Our Own – Stimpunks Foundation

Activity-Permissive Settings

ACTIVITY-PERMISSIVE SETTINGS are still the exception in schools and workplaces, but we ought to make them the rule; we might even dispense with that apologetic-sounding name, since low-intensity physical activity clearly belongs in the places where we do our thinking. Meanwhile, medium- and high-intensity activity each exerts its own distinct effect on cognition—as the psychologist Daniel Kahneman has discovered for himself.

The Extended Mind – Annie Murphy Paul

We’re tired of “Quiet Hands!”

We’re tired of “Cop Shit”.

We want Activity-Permissive Settings.

Let us fidget and stim.

“Sitting quietly,” the researchers conclude, “is not necessarily the best condition for learning in school.”

The continual small movements we make when standing as opposed to sitting—shifting our weight from one leg to another, allowing our arms to move more freely—constitute what researchers call “low-intensity” activity. As slight as these movements appear, they have a marked effect on our physiology:

It’s not only that such activity-permissive setups relieve us of the duty to monitor and control our inclination to move; they also allow us to fine-tune our level of physiological arousal. Such variable stimulation may be especially important for young people with attention deficit disorders. The brains of kids with ADHD appear to be chronically under-aroused; in order to muster the mental resources needed to tackle a difficult assignment, they may tap their fingers, jiggle their legs, or bounce in their seats. They move as a means of increasing their arousal—not unlike the way adults down a cup of coffee in order feel more alert.

She found that more intense physical movement was associated with better cognitive performance on the task. The more the children moved, in other words, the more effectively they were able to think. Parents and teachers often believe they have to get kids to stop moving around before they can focus and get down to work, Schweitzer notes; a more constructive approach would be to allow kids to move around so that they can focus.

Even among those without an ADHD diagnosis, the amount of stimulation required to maintain optimal alertness varies from person to person. Indeed, it may differ for the same individual over the course of a day. We have at our disposal a flexible and sensitive mechanism for making the necessary adjustments: fidgeting. At times we may use small rhythmic movements to calm our anxiety and allow us to focus; at other moments, we may drum our fingers or tap our feet to stave off drowsiness, or toy with an object like a pen or a paperclip as we ponder a difficult concept. All of these activities, and many others, were submitted to researcher Katherine Isbister after she put out a call on social media for descriptions of people’s favorite “fidget objects” and how they used them.

Her research and that of others suggests that fidgeting can extend our minds in several ways beyond simply modulating our arousal. The playful nature of these movements may induce in us a mildly positive mood state, of the kind that has been linked to more flexible and creative thinking. Alternatively, their mindless and repetitive character may occupy just enough mental bandwidth to keep our minds from wandering from the job at hand. One study found that people who were directed to doodle while carrying out a boring listening task remembered 29 percent more information than people who did not doodle, likely because the latter group had let their attention slip away entirely.

Perhaps most intriguing is Isbister’s theory that fidgeting can supply us with a range of sensory experiences entirely missing from our arid encounters with screen and keyboard. “Today’s digital devices tend to be smooth, hard, and sleek,” she writes, while the fidget objects she crowdsourced exhibit “a wide range of textures, from the smoothness of a stone to the roughness of a walnut shell to the tackiness of cellophane tape.” The words contributors used to describe their favored objects were vivid: such articles were “crinkly,” “squishy,” “clicky-clackety”; with them they could “scrunch,” “squeeze,” “twirl,” “roll,” and “rub.” It’s as if we use fidgeting to remind ourselves that we are more than just a brain—that we have a body, too, replete with rich capacities for feeling and acting. Thinking while moving brings the full range of our faculties into play.

“I don’t think fidget spinners should be banned. Teachers are often out of their depth with children with disabilities – the logic often is ‘I don’t understand it so get rid of it’.

Dr Sue Fletcher-Watson, Fidget spinners ‘soothing’ for autistic children and blanket ban in Scotland would ‘miss the point’, claims expert | The Scottish Sun

Regulatory and Adaptive Roles of Fidgeting

while stimming I am able to unravel the everyday ordinary barrage of sensory and social information that becomes overwhelming.

The Predictability, Pattern and Routine of Stimming | Judy Endow

Most of us stim because it calms us and helps alleviate our high levels of anxiety.

I can’t picture things in my head sitting still. I like to walk around and think.

Young Autistic Stimpunk

Sometimes I need a mind/body break. I need to be alone, I need to be in my head, and I need to stim. I stim by flapping my arms and clapping my hands while pacing. Stimming is a necessary part of sensory regulation. Stimming helps keep me below meltdown threshold.

- “Stimming is a natural behavior that can improve emotional regulation and prevent meltdowns in stressful situations.”

- “Let them stim! Some parents want help extinguishing their child’s self-stimulatory behaviors, whether it’s hand-flapping, toe-walking, or any number of other “stimmy” things autistic kids do. Most of this concern comes from a fear of social stigma.“

- “Self-stimulatory behaviors, however, are soothing, relaxing, and even joy-inducing. They help kids cope during times of stress or uncertainty.

- “You can help your kids by encouraging parents to understand what these behaviors are and how they help.“

Please proceed with what you are doing when I take a sensory break. I will observe from the edges and rejoin you when I am able.

- Restricted and repetitive behaviours and interests (RRBIs) have regulatory and adaptive roles.

- RRBIs help regulate sensory experiences.

- RRBIs can be strategies to cope with anxiety and introduce control to the environment.

- RRBIs help autistics to make sense of their worlds.

“What these fidget toys do is help reduce anxiety and manage sensory confusion – they give you something to focus on and allow you to block out other things that are harder to deal with.

“For autistic kids the classroom is already distracting – it’s colourful, disorganised, full off visual concepts, everyone is talking and they’re surrounded by smells from the teacher’s perfume to kids’ shampoo.

“It can be very overwhelming for autistic child – so something that gives a single focus is not a distraction, it’s the opposite, and enables them to carry on with their work.

“Lots of people will create their own sensory stimulation by flicking their hands or fingers – this is something we’ve known autistic children do to cope.

“There is the issue of distractability with ADHD, so the principle of providing a soothing focus could be beneficial.

“I think comes down to whether people willing to work with someone with ADHD or work against them.”

Dr Sue Fletcher-Watson, Fidget spinners ‘soothing’ for autistic children and blanket ban in Scotland would ‘miss the point’, claims expert | The Scottish Sun

As the autistic experience of the world differs from that of non-autistic people, so too does autistic behaviour. Understanding what is usual for an autistic patient facilitates care. Repetitive behaviour, which is common to autistic people, is termed ‘stimming’. It varies in manifestation and function, but may include hand flapping, whole body movements or the subtle use of fidget tools. In stressful situations, anxiety may be alleviated by stimming, so we advise encouraging the use of whatever tools a patient finds beneficial.

Autism and anaesthesia: a simple framework for everyday practice – ScienceDirect

Accept different expressions of sensory and communication preferences in employees as different but not wrong. Some people may prefer not to make direct eye contact or may use unconventional body language. Feeling free to stim (e.g., fidgeting, pacing, or chewing a pencil), or comfortable to show tics (including eye blinking, throat clearing) can help people to feel well regulated and to manage stress and anxiety.

- Predictive processing shows how seemingly pointless actions like fidgeting in fact can serve an uncertainty-reducing function.

- To resolve mounting uncertainty about the world, agents perform simple and precise actions, confirming their self-model.

- This proposal is extended to autistic stimming, which can be understood as a form of fidgeting.

Autistic adults highlighted the importance of stimming as an adaptive mechanism that helps them to soothe or communicate intense emotions or thoughts and thus objected to treatment that aims to eliminate the behaviour.

Furthermore, more recent theories have suggested that stimming may provide familiar and reliable self-generated feedback in response to difficulties with unpredictable, overwhelming and novel circumstances (e.g. Lawson, Rees, & Friston, 2014; Pellicano & Burr, 2012). As such, stimming may provide not only relief from excessive sensory stimulation, but also emotional excitation such as anxiety (Leekam, Prior, & Uljarevic, 2011). Consistent with these suggestions, autistic adults report that stimming provides a soothing rhythm that helps them cope with distorted or overstimulating perception and resultant distress (Davidson, 2010) and can help manage uncertainty and anxiety (e.g. Joyce, Honey, Leekam, Barrett, & Rodgers, 2017).

Reflecting the aims of popular interventions, language surrounding the topic of stimming is often pejorative (Jaswal & Ahktar, 2018). Researchers sometimes assume that stimming falls within voluntary control and has asocial or antisocial motivations (Jaswal & Ahktar, 2018; Lilley, in press). For example, a prominent review of repetitive behaviours in autistic people attributed the onset of stimming to a ‘self-imposed restricted environment’ (Leekam et al., 2011, p. 577). Stimming has become so associated with autism that some scientists and clinicians use the term ‘stims’ interchangeably with ‘autistic behaviour’ (Donnellan, Hill, & Leary, 2013). Furthermore, therapies continue to treat stimming despite lacking strong evidence of efficacy or ethics (Jaswal & Akhtar, 2018; Lilley, in press). While researchers increasingly acknowledge limitations in the understanding of, and interventions for, stimming (e.g. Harrop, 2015; Patterson, Smith, & Jelen, 2010), treatments may remain popular, in part because many parents regard it as noticeable and stigmatising (Kinnear, Link, Ballan, & Fischbach, 2016).

Autistic people have become increasingly mobilised and vocal in defence of stimming. Autism rights or neurodiversity activists believe that stims may serve as coping mechanisms, thus opposing attempts to eliminate non-injurious forms of stimming (e.g. Orsini & Smith, 2010). They decry practices such as ‘quiet hands’ (which teaches the suppression of hand flapping), instead using ‘loud hands’ as a metaphor both for using such non-verbal behaviour to communicate and for cultural resistance more broadly (Bascom, 2012). In addition, autistic scholar-activists denounce attempts to reduce their bodily autonomy (Nolan & McBride, 2015; Richter, 2017) and declarations of their stimming as unacceptable or as necessarily involuntary (Yergeau, 2016).

Using a thorough scoping review methodology, an examination of 21 studies revealed that RRBIs play an important role in helped autistic persons regulate sensory experiences, cope with feelings of anxiety, establish certainty and control in their environment, and make sense of their world. In contrast to the view that RRBIs in autism as negative interferences and targets to be subdued, this paper highlighted the constructive characteristics of RRBIs and provided an affirmative perspective that

Acceptance and Sensory-Based Approaches

“We need to identify childrens’ strengths in school and identify the tools to help them – fidget toys are part of that toolkit.”

Dr Sue Fletcher-Watson, Fidget spinners ‘soothing’ for autistic children and blanket ban in Scotland would ‘miss the point’, claims expert | The Scottish Sun

Research exploring general mental health has highlighted empirical evidence supporting the benefits of sensory-based approaches in the general population, where the physical environment is tailored to the sensory processing characteristics of an individual [397-401]. Sensory-based approaches can include strategies such as adjusting the room’s lighting and/or colours, providing access to weighted blankets, fidget tools, rocking chairs, and/or noise- cancelling headsets to reduce sensory stimulation. Sensory-based mental health approaches have been shown to create a sense of safety and control, increase self-regulation, reduce distress and anxiety, improve self-perception, and help with stabilising (or ‘grounding’) acute arousal [399, 401]. There is also emerging evidence suggesting that sensory-based approaches in inpatient mental health facilities may contribute to improvements in autistic individuals’ wellbeing and self-regulation [372, 402-403], giving further weight to the argument in support of ED services attending to the unique sensory needs of NDI.

Neurodivergence, Intersectionality, and Eating Disorders: A Lived Experience-Led Narrative Review

Encourage the use of comfort items and sensory aids such as noise-cancelling headphones, including right up to induction of anaesthesiawhere feasible. It is helpful to have a supply of inexpensive sensory aids available; these can include disposable ear plugs, sunglasses and a selection of fidget tools or tactile sensory aids.

Autism and anaesthesia: a simple framework for everyday practice – ScienceDirect

An autistic partner told us, “Having a visible box of fidget toys is something I find helpful, it’s a cue that this person/environment is safe to be myself”.

And the fact is, it’s easy. I’ve watched teachers create classrooms where every learner can get fully comfortable. They choose where, how, or if to sit. They lie on the floor and sit on the window sills, dangling their feet. They sit on couches. They have phones and often earbuds or headphones. The lighting is provided by thrift store task lighting. There are views out the windows and at least one blank wall that doesn’t assault learners’ vision. They’re not painted white (the medical field learned in the 1970s that white spaces increased pain perception for most patients). Learners can get up and walk out to a water fountain, to the toilet, just to walk, without anyone’s permission. They can eat, drink, fidget, and change positions. They can find something very close to privacy. In other words, everyone in the room can be a real human.

The Path to Equity Begins with Neuroqueer-Sensitive Learning Spaces – Stimpunks Foundation

Make Peace with Fidgeting: Think of It as Brain Development, Which It Is.

Ewan McIntosh echoes the Third Teacher in saying that teachers should ‘make peace with fidgeting’ , and realise that growing bodies often process information while moving.

Building a place to play and release energy, while providing tactile surfaces and activities; the need to fidget is pacified.

Make Peace With Fidgeting: Think of It as Brain Development, Which It Is., Make Peace With Fidgeting | Learning Ecologies Design Studio

Fidgeting, Monotropism, and Flow

Monotropic learners may find it more challenging to focus on a subject that is not intrinsically motivating for them. Fidget tools, doodling, and moving can all help to maintain a flow state, which may help some children cope better and be more regulated. It could improve concentration and learning outcomes and make learning a more enjoyable, less stressful experience. Monotropism is fluid; what works for one person may not work for another, and needs may vary from moment to moment depending on many social, physical, and sensory factors.

The Calm Joy of Engaging with Preferred Items

According to most autistic teenagers (N = 38), engagement with highly preferred items and activities helps them reach a state of calm happiness that cannot be compared with any other activity. This was often related to reaching a certain level of stimulation with activities that are not too easy or too hard, handling objects of great interest ‘independently, without interruptions (…) and developing a thinking routine around the ‘details of the objects and its history.’

They are all soft [the toy’s collection] and bring nice memories, some are presents from people I love (…) some are fidget toys to keep my hands busy and some (…) I have them all in a basket and go for them (…) [They] help me unwind my mind as I stare the ceiling trying to sleep.

Frontiers | A Good Night’s Sleep: Learning About Sleep From Autistic Adolescents’ Personal Accounts

Autistic Movement

In conclusion, body movements have both stigmatised and non-stigmatised appearances for autistic adults, but these cannot be distinguished by the function of the movement. Expressive, regulating and repetitive movements can be a well-being resource for autistic people. Implications for practice are discussed.

The meaning of autistic movements – Stephanie Petty, Amy Ellis, 2024

Conflicting Needs

Conflicts between the access needs of different individuals should be negotiated in class as part of the learning process.

Freedom of Embodiment

…freedom of embodiment—that is, the freedom to indulge, adopt, and/or experiment with any styles or quirks of movement and embodiment, whether they come naturally to one or whether one chooses them—is an essential element of cognitive liberty, and thus an essential area of focus for the Neurodiversity Movement. The freedom to be autistic necessarily includes the freedom to give bodily expression to one’s neurodivergence.