We simply are not Frankenstein monsters.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube, Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang – Fora

We simply are not Frankenstein monsters. We tend to focus on small mechanisms and parts and pieces of knowledge. Instead, focus on the whole person, not the Frankenstein monster with all the little pieces. Affective neuroscience teaches us new perspectives for understanding and appreciating the importance of the whole person in the educational context.

I’ve titled the talk this afternoon solving the Frankenstein problem, because we oftentimes, when we bring the evidence base to education, so called scientific basis for teaching practices, for the decisions we make in pedagogical contexts, we tend to focus on small mechanisms and parts and pieces of knowledge…

…

But what I’m going to argue is that that kind of evidence base has very limited utility in the kind of work that you’re going to be doing. What you’re doing is not improving executive control and phonological decoding and mathematical computational capacity. You’re actually teaching a whole child, a whole group of whole children, young adults, adolescents, to think in ways that enable them to do science, in ways that enable them to build capacities to be a scientist.

You’re enabling them to think not just about mathematical concepts and numbers, but to engage with those in an active, civically oriented way that enables them to give back to society with their knowledge. You’re focusing on the whole person, not the Frankenstein monster with all the little pieces. And so I’m going to talk to you about how the data really teaches us new perspectives for understanding and appreciating the importance of the whole person in the educational context. And, of course, you’re a whole person, too.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube, Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang – Fora

Progressive, human-centered education provides a holistic, experiential, responsive, neurobiological approach to solving the Frankenstein problem.

We’re raising whole children, not Frankenstein children. That is a useful re-framing. It’s a re-framing that confronts biological essentialism, neuroessentialism, scientific essentialism, selfish-gene notions of human nature and evolution, evidence-based claims, scientism, BGUTI, and other major narrative obstacles.

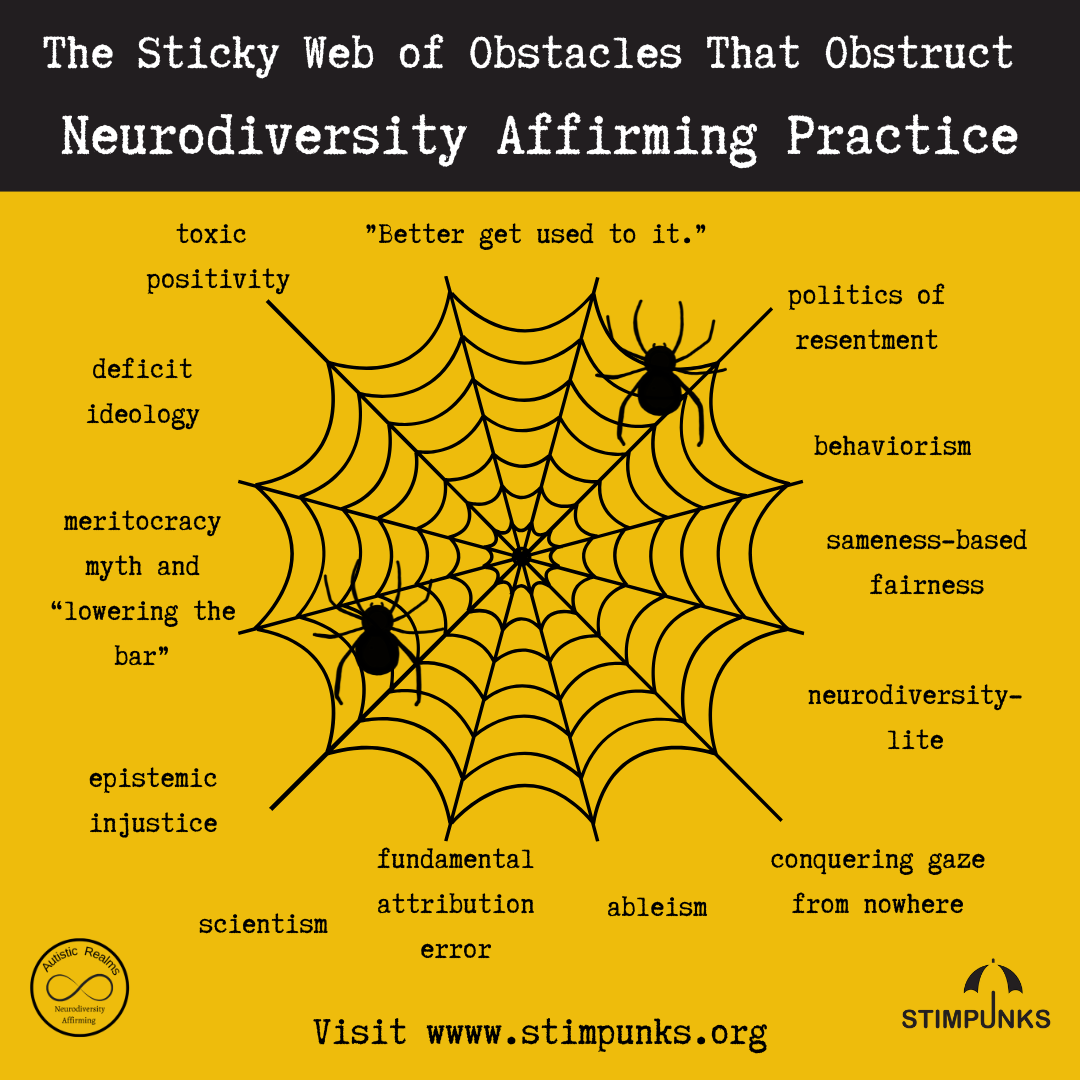

Obstacles to DEI-AB and Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

(links are to our glossary, where you can learn much more)

- politics of resentment

- sameness-based fairness

- fundamental attribution error

- conquering gaze from nowhere

- toxic positivity

- neurodiversity-lite

- scientism

- epistemic injustice

- behaviorism

- ableism

- deficit ideology

- ”Better get used to it.”

- meritocracy myth

- “lowering the bar”

politics of resentment = manipulations of status anxiety; organization of interest groups based on perceived deprivation or the threat of deprivation

sameness-based fairness = notion of fairness where everyone gets the same thing rather than each getting what they need

fundamental attribution error = to underestimate the impact of situational factors and to overestimate the role of dispositional factors in controlling behaviour

conquering gaze from nowhere = the interpretation of objectivity as neutral and not allowing for participation or stances; an uninvolved, uninvested approach that claims objectivity to “represent while escaping representation”

toxic positivity = belief that success happens to good people and failure is just a consequence of a bad attitude rather than structural conditions

neurodiversity-lite = using neurodiversity as a buzzword; a way to profit from the appropriation of a human rights movement; a cottage industry for therapists, clinics, and companies to sell their associated products, classes, books, and training to the public without having a clue about neurodiversity

scientism = the belief that science is the only route to useful knowledge

epistemic injustice = where our status as knowers, interpreters, and providers of information, is unduly diminished or stifled in a way that undermines the agent’s agency and dignity

behaviorism = a dehumanizing mechanism of learning that reduces human beings to simple inputs and outputs

ableism = a system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness

deficit ideology = a worldview that explains and justifies outcome inequalities by pointing to supposed deficiencies within disenfranchised individuals and communities

better get used to it = preparing people for oppression by oppressing them

meritocracy myth = a widely held but false assertion that individual merit is always rewarded; the myth of meritocracy is one of the longest lasting and most dangerous falsehoods in American life

lowering the bar = a racist, sexist, and ableist narrative with no basis in reality that represents diversifying hiring pipelines, attracting candidates from underrepresented groups, and supporting them in the workplace as “lowering the bar” by hiring less-qualified individuals

It’s really not that we are Frankenstein monsters with complex thinking over here and emotion over there, but in fact, they are: complex thinking is the legacy of the emotional feelings we’re able to conjure as we build feelings and narratives that reflect our knowledge, that reflect our experience, that reflect our proclivities and dispositions of mind and that are emergent within the cultural context in which we live and situate ourselves. So emotionally engaged thinking activates the same brain systems that keep you alive.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

Complex Thinking Is the Legacy of Emotional Feelings

So emotions are a critical piece of learning always.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

We are not isolated inside our own skulls. We are, in fact, deeply interdependent in the ways that give emergence to all kinds of potentials. In other words, biologically speaking, culturally speaking, socially speaking, cognitively speaking, developmentally speaking, we are interdependent on one another to co-create one another’s environment for neural functioning. Literally, we depend upon the others. Just like the ocean here is sloshing us and bolstering up our brains, we are the ocean for one another, and we are also being sloshed and bolstered by those around us.

What the biological sciences are now showing, which is incredibly, I think, important for educators to understand, is the very deep and profound nature of our biological interdependence and the emotional and social realities of that biological dependence.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

How is it that our genes produce the minds we have? They don’t. Basically, our genes are a kind of contingency plan. They’re a set of tools that can be used by the individual, unfolding in context to build things, to build ways of being. And so the genes are a piece of the toolkit. But how people think and feel is directly organizing their mind, their brain, and their health over time.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

Our biology is dependent upon the social conduits, the emotional and cultural situatedness of ourselves, our bodies, and our minds.

And that is actually why teaching is so critical for the future of America’s youth and all of the world’s youth

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

We think that the reason that humans values and belief systems and ideals are such powerful motivators is literally that they’re hooking themselves into biomechanical machinery that has evolved to keep us alive over time. So emotions are a critical piece of learning always.

Meaningful learning, learning that really matters to you, that changes who you are and that endures over time, always has an emotional component.

Understanding complex ideas is a very powerful emotional experience for human beings, and that is what you’re aiming for in the classroom.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang – Fora

I would argue that relevance in the context of disciplinary learning for adolescence is the experience of feeling like me while I’m thinking about ideas.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

Meaningful learning shifts teachers and students, I would argue, from emotions that are about the outcome, the result, the correct answer, to emotions that are about the ideas.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

Recent research in cognitive science and the neurobiology of learning has shown that emotion, affect, feelings are central to all experience, including learning information and analyzing complex scenarios. As humans have evolved from our other animal ancestors, as we’ve added increased cognition afforded by the prefrontal cortex, as we are capable of self-awareness and metacognition and have changed some of the ways brains function at the cellular level, we also preserve all the other dimensions of our prehuman neuro-architecture, having to do with sensory input, motor control, and emotion.

In their masterwork, The Archaeology of Mind, Jaak Panksepp and Lucy Biven argue that all animals, not only mammals, have seven emotional systems: seeking, fear, rage, lust, care, grief, play, self. All are present at all times, even when “higher” cognitive levels are emphasized. These emotional systems help motivate (notice this word; we’ll return to it) and protect, causing animals to draw near certain things, to avoid certain behaviors, to increase certain activities that produce positive responses, for example to work very long hours to invent a new vaccine for a world-ravaging virus. All these systems contribute to survival, but some are not only about brute survival and reproduction and eating. Many also have to do with security and further with notions of integration, exploration, and connections. Some are responsible for play.

Neuroscience researchers such as Antonio R. Damasio have shown that it’s not possible to learn well without some emotional work being managed. We usually think of rational, ethical decision making as something that involves only cognition, but decades of work have demonstrated the essential involvement of emotion: “the reasoning system evolved as an extension of the automatic emotional system, with emotion playing diverse roles in the reasoning process.” Sure, emotion can mislead us. But “when emotion is entirely left out of the reasoning picture, as happens in certain neurological conditions, reason turns out to be even more flawed than when emotion plays bad tricks on our decisions.” So even if we believe that the goals of schooling are entirely cognitive, we can’t neglect emotion; it’s not just an added nuisance or necessary adjunct. (Damasio also was interested not only in morality but in aesthetics; the brain is involved in aesthetic experiences as well.) Annie Murphy Paul in The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking outside the Brain shows that bodily knowledge (interoception) can be more accurate, for instance in the work of day traders who must juggle huge amounts of information very rapidly, than conscious analysis of explicit data. “The heart, and not the head, leads the way,” she concludes. Leslie Shelton puts it bluntly: “Emotion is the master over cognition.”

Despite emotion lying at the core of well-being and suffering, despite existentialist philosophers’ and existentialist psychologists’ interests in human experience, and phenomenologists’ focus on what it feels like to be or to do a certain thing, the study of emotion has come relatively late to students of education, especially higher education.

James Zull, a biologist, started learning about how people learn—neurologically. He found, to his surprise, that it was not all cognitive and analytic, though this follows directly from a detailed understanding of how brains are organized and how they learn. His book The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the Practice of Teaching by Exploring the Biology of Learning includes not just one but two chapters on emotion and feeling: “A Feeling of This Business: In the Business of Reason and Memory, Feelings Count” (chapter 5), and “We Did This Ourselves: Changing the Brain through Effective Use of Emotion” (chapter 12). Based on experiments in his own classes and watching others teach, both well and badly, he learned the importance of getting students’ emotions on board. This happens when certain conditions hold: students see the big picture; motivation follows learning; stories help people care; teachers have to be real; and students need to feel that the learning is theirs and directed by them, not merely by the teacher’s orders. He stumbled upon self-evaluation, just as I did.

But in the context of school, being and feeling are often left unexamined.

Blum, Susan D.. Schoolishness: Alienated Education and the Quest for Authentic, Joyful Learning (pp. 35-37). Cornell University Press.

We Are Not Pigeons

We’ve conflated science with scientific management for too long. This is a reason why Mary Helen Immordino-Yang’s work is so compelling to us. Science, especially when it comes to humans, should be foregrounding complexity and diversity as the baseline. Progressive education recognizes and respects this complexity. The reductionism and scientism of mainstream education does not.

Our students are not surgically modified dogs nor are they pigeons in operant conditioning chambers attempting to learn nonsense words. No child enters a classroom devoid of emotion, interest, or prior knowledge. Owing to the key distinctions between the controlled laboratory and the living classroom, there simply may be no connection between what is taught and what is learned; or between the educational intervention and the desired outcome. This is why, in pedagogies centered on instruction drawn from the narrow view of “The Science of Learning,” behaviorism is a complexity control meant to reduce the number of possible variables between instruction and assessment; to better reproduce the uncomplicated relationship between variables in the Skinner Box. We know from listening to students themselves that there has been a persistent crisis in schools, even before COVID: students ask fewer questions the longer they remain in school, engagement plummets alongside mental health, and absenteeism surges. Ultimately, any science of learning matters far less than its implementation. Maintaining fidelity to what happened in, say, Pavlov’s lab matters significantly less if the practices derived from his work contribute to stress, anxiety, and alienation in students.

If the perfect education system requires that you dehumanize the people in it — adults and kids alike — that’s not a system that “works” by most metrics worth caring about. The kids in our schools have to be viewed as more than behaviorist subjects to be acted upon. If we at least admit that much, then the business of teaching gets far more complicated. Suddenly there are a number of other factors we must tend to that matter a great deal. I’ll quote again from apparent “pseudoscientist” Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, “As human beings, feeling alive means feeling alive in a body but also feeling alive in a society, in a culture; being loved, being part of a group, being accepted, and feeling purposeful.” These are self-evident truths that we are finally beginning to explore the neurobiological basis for in ways that shatter many previous models of the brain that still hold cultural sway.

Beyond Pavlov’s Perfect Student | Human Restoration Project | Nick Covington Michael Weingarth

Research increasingly recognizes that, as medical researchers Peter Stilwel and Katharine Harmon write, “Cognition is not simply a brain event.”(*) Drawing from their intuitive 5E model, we can better understand learning as a process of sense-making about ourselves in relation to the world that is:

Embodied – sense-making shaped by being in a body

Embedded – bodies exist within a context in the world

Enactive – active agents in interactions with the world

Emotive – sense-making always happens in an emotional context

Extended – sense-making relies on non-biological tools and technologies

Rather than rely exclusively on tests of memory and retention, as The Science of Learning would direct us, this holistic 5E model lives at the intersection of the multiple missions of school: to provide an emotionally and physically safe and productive environment, to promote social and emotional growth, to develop executive skills and self-regulation, and to improve the intellectual capacity of kids to be active agents in the world. Summarized beautifully by education, psychology, and neuroscience professor Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, “As human beings, feeling alive means feeling alive in a body but also feeling alive in a society, in a culture; being loved, being part of a group, being accepted, and feeling purposeful.”

There is No Such Thing As “The Science of Learning” | Human Restoration Project | Nick Covington Michael Weingarth

Somatic Rudders: Poets had it right all along.

What we discovered was that these regions are visceral somatomotor cortex, they are the feeling and regulation of the state of your guts and viscera. When people experience deep emotionally engaged thinking about complex issues, they are literally playing out that thinking process, our data would suggest and now many other sources of data would suggest, on the substrate of the cortisone cortical regions that literally also are feeling your guts.

Poets have had it right all along.

Keynote: Dr. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang | Solving the Frankenstein Problem – YouTube

Put simply, the poets had it right all along: feeling emotions about other people, including in moral contexts such as for judgments of fairness, virtue, and reciprocity, involve the brain systems responsible for “gut feelings” like stomachache (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Lieberman & Eisenberger, 2009) and systems that are responsible for the construction and awareness of one’s own consciousness (i.e., the experience of “self”; Damasio, 2005; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, & Zahn, 2008; see also Chapter 2).

Emotions, Learning, and the Brain: Exploring the Educational Implications of Affective Neuroscience

Far from divorcing emotions from thinking, the new research collectively suggests that emotions, such as anger, fear, happiness, and sadness, are cognitive and physiological processes that involve both the body and mind (Barrett, 2009; Damasio, 1994/2005; Damasio et al., 2000).

Emotions, Learning, and the Brain: Exploring the Educational Implications of Affective Neuroscience

Sensing and labeling our internal sensations allows them to function more efficiently as our somatic rudder, steering a nimble course through the many decisions of our days. But does the body really have anything to contribute to our thinking—to processes we usually regard as taking place solely in our heads? It does. In fact, recent research suggests a rather astonishing possibility: the body can be more rational than the brain. We’ve conflated science with scientific management for too long. This is a reason why Mary Helen Immordino-Yang’s work is so compelling to me. Science, especially when it comes to humans, should be foregrounding complexity and diversity as the baseline. Progressive education recognizes and respects this complexity. The reductionism and scientism of mainstream education does not.

Paul, Annie Murphy. The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (p. 29). HarperCollins.