“My whole life has been a process of finding labels that fit.”

“My whole life has been a process of finding labels that fit”: A Thematic Analysis of Autistic LGBTQIA+ Identity and Inclusion in the LGBTQIA+ Community | Autism in Adulthood

The deconstruction has begun

Time for me to fall apart

And if you think that it was rough

I tell you nothing changes

Till you start to break it down

And break apart

I'll break apart

I'll break apart

Right now it's going to start

I'll break apart

The reconstruction will begin

Only when there's nothing left

But little pieces on the floor

They're made of what I was

Before I had to break it down

The Deconstruction by The Eels

Gender Copia and Bricolage

Autistic people, who are less aware of social norms, are less likely to develop a typical gender identity. Instead of gender as a binary or even a continuum, “Gender Copia: Feminist Rhetorical Perspectives on an Autistic Concept of Sex/Gender: Women’s Studies in Communication: Vol 35, No 1” presents gender as a fluid and multidimensional copia.

Due both to their ability to denaturalize social norms and to their neurological differences, autistic individuals can offer novel insights into gender as a social process. Examining gender from an autistic perspective highlights some elements as socially constructed that may otherwise seem natural and supports an understanding of gender as fluid and multidimensional.

Gender Copia: Feminist Rhetorical Perspectives on an Autistic Concept of Sex/Gender: Women’s Studies in Communication: Vol 35, No 1

Confronting and denaturalizing social norms describes the terrain of many autistic lives. We’re social construct canaries.

Autistic writers often invite alternative understandings of sex=gender as a multiple, rhetorical phenomenon. Autobiographies, blogs, and Internet posts show how autistic individuals view gender as a copia, or tool for inventing multiple possibilities through available sex=gender discourses. Four particular discourses emerge through which autistic people understand gender: identification, neurodiversity, performance, and queer identity.

Gender Copia: Feminist Rhetorical Perspectives on an Autistic Concept of Sex/Gender: Women’s Studies in Communication: Vol 35, No 1

The article goes on to propose a gender copia that sounds like our kind of bricolage.

Language is not a set menu, it’s a buffet.

Spider-Verse, Identity Politics, Leftist Infighting, and the Oppression Olympics – YouTube

The sources considered here imply not a binary model (masculine=feminine) or even a view of gender as a continuum, but something more like a copia, the rhetorical term Erasmus used to describe the practice of selecting ‘‘certain expressions and mak[ing] as many variations of them as possible’’ (17). Copia provides a strategy of invention, a rhetorical term for the process of generating ideas. To be specific, copia involves proliferation, multiplying possibilities so as to locate the range of persuasive options available to a rhetor. I find the concept of invention fitting to describe the kind of rhetoric in which many autistic individuals engage when they discuss sex and gender, a rhetoric we might consider, following Mary Hawkesworth, a feminist rhetoric, insofar as it seeks to ‘‘call worlds into being, inscribe new orders of possibility, validate frames of reference and forms of explanation, and reconstitute histories serviceable for present and future projects’’ (1988).

Individuals who find themselves engaged in this rhetorical search for terms with which to understand themselves can draw on a wide array of terms or representations, such as genderqueer, transgendered, femme, butch, boi, neutrois, androgyne, bi- or tri-gender, third gender, and even geek.

Gender Copia: Feminist Rhetorical Perspectives on an Autistic Concept of Sex/Gender: Women’s Studies in Communication: Vol 35, No 1

Autistic people have a reputation for being rigid, but it’s NT society that enforces strict rules, conventions and traditions. Meanwhile, autistic people are recognising and preaching the fluidity and/or flexibility of things like sexuality, gender, time, love, career and more.

@AutisticCallum_

Gender Copia: Feminist Rhetorical Perspectives on an Autistic Concept of Sex/Gender: Women’s Studies in Communication: Vol 35, No 1

These findings suggest a prevalence of nonbinary identities not thoroughly examined in the current academic autism literature. This indicates a need for further focus on definitions of gender outside of the binary in the autistic population. Nonbinary identities are valid, and nonbinary individuals have the right to access care and support, including services initially created based on binary conceptualizations of gender. These findings reveal that autistic individuals hold diverse and nuanced views of their gender identities.

What Category Best Fits: Understanding Transgender Identity in a Survey of Autistic Individuals | Autism in Adulthood

Gender Subjectivity

In the simplest possible terms, I propose that gender identity is how we make sense of our gender subjectivity, the totality of our gendered experiences of ourselves. Gender identity is constituted by gender subjectivity, but this constitutive relationship is underdetermined. While gender subjectivity may narrow the range of inhabitable gender identities, it is always compatible with more than one. To arrive at a gender identity, we arrange gender subjectivity like building materials. My theory helps us understand how different people offer seemingly incompatible accounts of their gender identity without questioning their authenticity or validity. They simply arrange similar building materials differently.

What Is It like to Have a Gender Identity? | Mind | Oxford Academic, Perma | www.florenceashley.com

Because the psychological synthesis of gender subjectivity into gender identity is particular to the individual, accounts of gender identity that would be stereotyping or bioessentialist if universalized remain acceptable at the individual level— voiding of all exigency the temptation to question the validity or authenticity of anyone’s gender identity.

What Is It like to Have a Gender Identity? | Mind | Oxford Academic, Perma | www.florenceashley.com

What Is It like to Have a Gender Identity? | Mind | Oxford Academic, Perma | www.florenceashley.com

@floral_ashes • The core thesis of the paper is that people construct gender identity from an endless list of mor… • Threads

The Neurodiversity Smorgasboard

A related concept to gender copia and the building blocks of gender subjectivity is the Neurodiversity Smorgasbord.

If you’re wondering why I picked a smorgasbord of all things, it was inspired by the relationship smorgasbord; a concept that explains how every relationship is unique and made up of different aspects, roles and goals. Instead of defining a relationship as strictly platonic or strictly romantic, it allows individuals to move away from labels and be specific. I believe this applies to neurodiversity. Instead of defining individuals by diagnostic labels, we want to be specific and acknowledge each person’s unique differences and traits.

If we’re rolling with the analogy of a smorgasbord, there are a lot of different ingredients that make up the diversity of our minds. You could say each individual is a plate of various ingredients and tasty treats. Each of us are our own unique combination of ingredients and there are infinite combinations of ingredients. There are so many variations of ingredients too. For example, imagine cheese as communication differences – there are many ways to communicate as there are many cheeses. Some of us might have Parmesan on our plate, some of us might have tripe Brie, some of us might have cheddar and many of us might even have a cheese board, a combination of cheeses. In other words, a combination of communication differences. Many of us might have an ingredient or five that’s common with a lot of people while some of us have ingredients that are less common. Some of us might have ingredients in common but perhaps prepared a different way. And some of us have ingredients that people look down upon, that they judge, like pineapple on pizza.

The Neurodiversity Smorgasbord: An Alternative Framework for Understanding Differences Outside of Diagnostic Labels — Lived Experience Educator

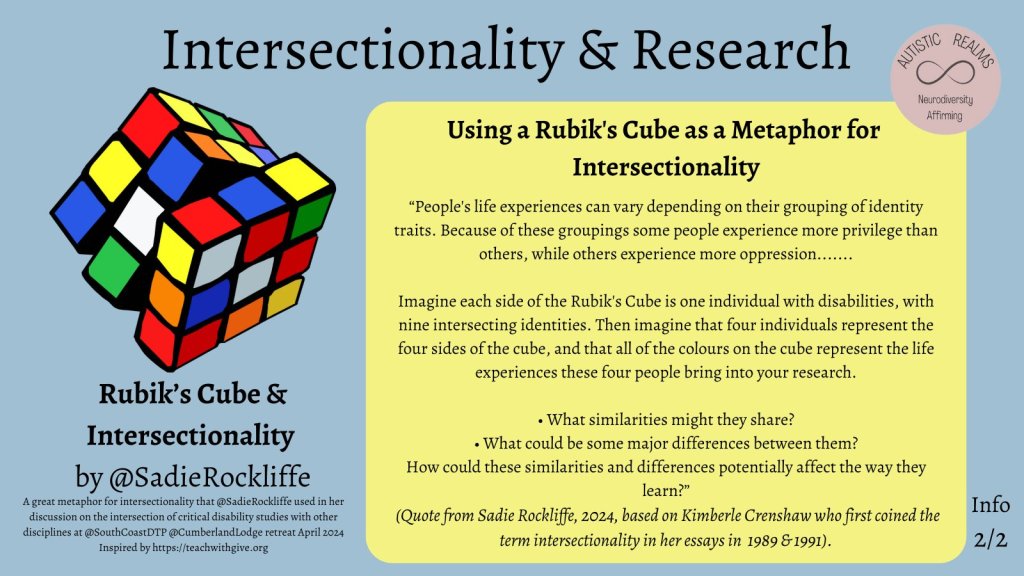

Using a Rubik’s Cube as a Metaphor for Intersectionality

Using a Rubik’s Cube as a Metaphor for Intersectionality

“Imagine each colour represents a different type of social identity (e.g., red for ethnicity) or identity trait.

Here, the unsolved Rubik’s Cube illustrates how much variety there can be in identity groupings. This is a reflection of the disability population.

People’s life experiences can vary depending on their grouping of identity traits. Because of these groupings some people experience more privilege than others, while others experience more oppression.”

(Quote from Sadie Rockliffe, 2024, based on Kimberle Crenshaw who first coined the term intersectionality in her essays in 1989 & 1991).

“People’s life experiences can vary depending on their grouping of identity traits. Because of these groupings some people experience more privilege than others, while others experience more oppression……

Imagine each side of the Rubik’s Cube is one individual with disabilities, with nine intersecting identities. Then imagine that four individuals represent the four sides of the cube, and that all of the colours on the cube represent the life experiences these four people bring into your research.

- What similarities might they share?

- What could be some major differences between them?

How could these similarities and differences potentially affect the way they learn?”(Quote from Sadie Rockliffe, 2024, based on Kimberle Crenshaw who first coined the term intersectionality in her essays in 1989 & 1991).

Rhizomatic Becoming

This chapter uses rhizomatic becoming (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988) as an analytical framework as we explore gender identity, embodiment, and unmasking. Milton (2017) suggests that

Autistic ways of being can be seen as being constructed as “rhizomatic”: a psychologic system that has no parameters, no hierarchy nor status, but seemingly endless “connections” in which constructions of Autistic self and identity may be shaped by “rhizomatic memory.”

(Pearson & Rose, 2023)

Rhizomatic becoming, reminiscent of Autistic perceptions, is a process of unmasking and expressing our Autistic selves.

Becoming is fluid (Carlström, 2019). Moving from a position of “being” to “becoming” opens the possibility for change, transformation, and creative potential (e.g., in embracing different identities than others have prescribed for us). As related to gender divergence, it is crucial to position gender as “always to come” (Linstead & Pullen 2006, p. 1292), “something one becomes rather than something one is (Cordoba, 2022, p. xiii). The conceptualisation of an ever-moving self (where some aspects of identity become an integral part of “who I am” and others are fluid, expressed through the lived body Desmond, 2023) echoes our experiences of exploring multiple identities.

“Always to come” might be figured in the imagination but does not necessarily imply a preconceived idea that can be foreseen as a finished product. Cordoba (2022) described that a crucial part of gender becoming was exploration of embodiment and gender expression (e.g., indexing a nonbinary identity through fluctuating aesthetics such as clothing, hairstyles, makeup; Morrison, 2023). We conceptualise embodiment as “both a state (corporeality) and a process (becoming aware of and identified with myself as corporeal” (Totton, 2015, p. 57, emphases original).

We include a focus on shifting embodiment as part of our becoming (e.g., changing external appearance or getting ink). These can act as “a tool, a process of exploring ourselves. It is adventure, discovery, surprises, changes . . . a beginning, a transformation, an ending, and anything else” (Rehor & Schiffman, 2022, p. 11). We suggest that ink and kink can be structures for unmasking as both are a process of noticing and negotiating what is in the differential between the felt world and the abstraction of linguistics of identity. We argue both ink and kink are a practice of bodying (Manning, 2020) and therefore becoming and unmasking. Manning (2020) employs bodying as a verb, pointing out the stakes of individuation: the policing of bodies “denies bodies of their potential transitions, of their becomings, imposing an identity on them that cannot be assimilated” (p. 219). As implied by Sarenius’s (2022) masks, shifting embodiment can be simultaneously part of our becoming and unmasking. Getting tattooed and engaging in kink3 relies on a reciprocal process of becoming: first, a negotiation, wherein the potential for a new identity emerges, then a relational expression based on deep connection and trust: a concrete way in which to experience the “felt sense of the other person, and the other’s felt sense of me” (Totton, 2015, p. 32).

In this negotiation, some aspects of becoming depend on relationship and recognition. Until then, we can be suffocated by our mask and not even recognise its existence let alone name it: “Until the situation is right for meaning to become more itself in the special way that language allows, it remains unformulated. The act of formulation, that is, takes place only when meaning is ‘ready’ to become more than it has been; and to be ready it must percolate for as long as it takes” (Stern, 2019, p. 7).

Exploring Autistic Sexualities, Relationality, and Genders: Living Under a Double Rainbow

Quoting Deleuze and Guattari (1987), Linstead and Pullen (2006) suggest that gender identity is

constant becoming, a constant journey which must start and end in the middle because “a rhizome has no beginning and no end: it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo” (p. 25). As Adkins (2015) explains, a rhizome is non-hierarchical, instead its connections are lateral, unpredictable, it creates the new but without linearity, with no guarantee of what will be created. Any of the rhizome’s connections can be cut, disconnected, reformed, always leading to new possible connections. This is to say, becomings are not straightforward, and ours is no exception. This chapter and its style is rhizomatic – it changed during its writing and is not the same chapter as originally conceived. We had not anticipated the chapter would itself be part of our becoming; and yet, as we allowed ourselves to exist in the “chaotic realm of knowing and unknowing.”

(Halberstam, 2011, p. 2)Darting forward and back in what we dared and felt safe to say, the chapter located its own becoming. We purposefully present an account that holds complexity in its reading4 to reflect the nature of rhizomes which pursue “connections that transform it, creates something new. A rhizome has no up and down, right or left, it is always in the middle” (Adkins, 2015, p. 24).

Exploring Autistic Sexualities, Relationality, and Genders: Living Under a Double Rainbow

Autistic identification is categorical and therefore can bring the baggage of identity politics. However, Autistic people continue to shape what this looks like in ways that directly attempt to dismantle the diagnostic gaze via the language of its own mechanisms. Furthermore, formal identification9 can foster continuing exploration of being Autistic, crossing into an examination of gender identities/sexual preferences. Part of our becoming and (un)masking is having access to the language through which to understand and communicate our gender, our neurodivergence, and so on. How do we locate ourselves without words or other reference points through which to orient ourselves? Formal identification of Autistic identity can be an origin story moment, a linguistic container with which to take the mask apart.

Exploring Autistic Sexualities, Relationality, and Genders: Living Under a Double Rainbow

Davidson and Tamas (2016) turned to the idea of the “ghost” to explain the way Autistic people often innately perceive the performance of gender and the way it can haunt us, manipulate us, animate us, rally others for us, or put a target on our backs when we fail to perform it (p. 61). Gender seems like the ghost everyone is hunting. Perhaps, it is that Autistic people are especially attuned to the falsity of this abstraction.

Exploring Autistic Sexualities, Relationality, and Genders: Living Under a Double Rainbow

Avoiding Essentialism

The most influential softer naturalist alternative (Kendler et al., Citation2011) frames psychiatric classifications as mechanistic property clusters. This notion indicates categories defined in light of a whole range of characteristic (although not singularly essential) factors that interact with each other causally and at varying levels (e.g., biological, psychological, behavioral) (Kendler et al., Citation2011). Within this framing, at least some natural kinds that lack fixed essences – most notably, species – can be thought of as complex sets of entities with “various degrees of causally supported resemblance” (Boyd, Citation1999, p. 144), insofar as they possess similar properties in light of related causal links. With psychiatric classifications, Kendler (Citation2016, p. 9) notes how

[Mechanistic] property clusters can allow us to “soften” the unsustainable demand for true “essences” in realistic models for psychiatric disorders. They give us a tractable kind of “emergent” pattern. What makes each psychiatric disorder unique are sets of causal interactions amongst a web of symptoms, signs and underlying pathophysiology across mind and brain systems.

Full article: The reality of autism: On the metaphysics of disorder and diversity

Underlying living sense-making is a basic tension between self-production and self-distinction (Maturana and Varela, 1980; Varela, 1979). Living beings continually construct themselves out of the environment, and in doing so, also continually distinguish themselves from the environment. Sense-makers deal with the tension between these opposing tendencies by regulating their couplings with their environment in view of their metabolic, sensorimotor, and intersubjective needs and constraints and what the environment has to offer—what we call agency. In this way, enactive sense-makers are continually individuating themselves and ongoingly becoming in interaction (Di Paolo, 2018, 2020; Di Paolo et al., 2018).

Seeing and inviting participation in autistic interactions, Hanne De Jaegher

The gender essentialist mindset, which can admit no gender possibilities other than two allegedly innate and immutable “biological sexes,” is inimical to gender creativity and to the realization of the infinite range of gender possibilities. By the same token, an overly neuroessentialist mindset—a mindset which conceives of human neurodiversity as consisting of little more than an assortment of largely innate and immutable “neurotypes” or “types of brains”—is an obstacle to the realization of the infinite range of neurocognitive possibilities, and to the realization of our full potentials for intentional creative queering of our minds.

Walker, Nick. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Autonomous Press.

Public discourses on human diversity, including the discourses on gender, sexual orientation, and neurodiversity, occur almost entirely within the framework of identity politics—a framework which is fundamentally essentialist, since it involves sorting people into identity categories which tend to be presented as largely innate and immutable. Those who are accustomed to viewing queerness through this lens are often surprised to learn that the field of Queer Theory tends to reject essentialism and thus to depart radically from the premises of identity politics.

Walker, Nick. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Autonomous Press.

In conceptualizing gender as being constructed through ongoing socially instilled performances which can be subverted and altered (i.e., queered), Queer Theory frames identity as a fluid byproduct of activity: gender and sexuality are first and foremost things that one does, rather than things that one is, and queer is a verb first and an adjective second. In other words, one is queer not because one was born immutably queer on some sort of essential genetic level, but because one acts in ways which queer heteronormativity (e.g., going outside the boundaries of the binary gender category to which one was assigned at birth, or engaging in non-heteronormative sexual activity)

Walker, Nick. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Autonomous Press.

One is neuroqueer not because one was born immutably neuroqueer, but because one acts in ways which queer neuronormativity.

Walker, Nick. Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Autonomous Press.

Shedding Labels

A list of words and identities doesn’t really begin to scratch the surface of my experience and it’s making me more insular than I’d like.

Yet these labels also connect me to others. When I do research with people I share identities or life experiences with, it’s important they know who they’re sharing their stories with. If this experience can be conveyed in a few labels then that makes things easier for everyone.

Going forward I will only share specific labels to support others or to get accommodations myself. The world doesn’t need a list of my embodiments.

I’m reveling in the shedding of labels whilst appreciating the immense privilege I have to know who I am, to have words for my experiences, and the resources to find my own.

Shedding my labels

I Don’t Feel Like a Gender, I Feel Like Myself

Participants reported not identifying with typical presentations of the female gender for a variety of reasons, linked both to autism and to sociocultural expectations. Participants described childhoods of being a tomboy or wanting to be a boy, having difficulties conforming to gender-based social expectations and powerful identifications with their personal interests.

“I Don’t Feel Like a Gender, I Feel Like Myself”: Autistic Individuals Raised as Girls Exploring Gender Identity

The discussion looks at how autistic people are sometimes forced to act in certain ways to fit in, and how this can make them feel confused and depressed. The research design was led by the participants and this meant that a group who have rarely been asked their opinion were able to have a say.

Notably, all participants in this discussion felt that they did not relate to the typical presentation and activities of the female gender.

“I Don’t Feel Like a Gender, I Feel Like Myself”: Autistic Individuals Raised as Girls Exploring Gender Identity

I believed myself to be a boy and was mortified and sick when I start developing as a girl.

Ruth

A number of participants described occasionally enjoying activities that they considered to be typically female as well as activities they considered to be typically male:

I always had a pretty even split of ‘‘girl toys’’ and ‘‘boy toys’’—baby dolls, Ninja Turtles, stuffed animals, Ghostbusters, stickers, dinosaurs, crafty stuff, Lego.

Kate

Most participants reported having a fluid sense of gender, being gender-queer, or feeling male and female and seeing others in the same way. For example, Clare described:

Love & desire have more to do with the personality of the individual than gender does.

Clare

An absence of a sense of gender or being unsure of how their gender should ‘‘feel’’ was another common report:

As a child and even now, I don’t ‘feel’ like a gender, I feel like myself and for the most part I am constantly trying to figure out what that means for me.

Betty

Many participants also described feeling agender or not identifying with a gender:

I don’t feel like a particular gender I’m not even sure what a gender should feel like.

Helen

Only one participant reported themselves as being trans- gender:

I remember the first time I read about gender dysphoria in a psychology book I understood myself and gender. I am a man in a female body, [.] I have been a boy who has grown into a strong, gentle man.

Mike

Participants also noted that some of their experiences reflected prevalent attitudes when they were children. As Sally reflected:

Sometimes I wish I was born during today’s times. Today is a different age, and so many differences are being accepted and embraced. Maybe there’s much more hope in the future if things keep going that way.

Sally

Participants also described ‘‘masking’’ their autistic behaviors during childhood but tended to view this as something they resisted as adults.

I am even less likely to conform to anything now that I’m older.

Rachel

Participants also discussed how discovering their autistic identity has helped them accepting themselves. Sally said:

Finding out that I am an individual with autism has helped me understand myself a lot. It explains why I’ve been so different and why I struggle with male/female roles and identity. It helps me to better accept myself. It doesn’t solve the struggles, but it helps with my own personal acceptance.

Sally

Of particular note is the extent to which interests played a role in defining both gender identity and identity in general. Most participants within this study characterized their sense of identity as ‘‘fluid’’ and defined more from their interests:

My sense of identity is fluid, just as my sense of gender is fluid [.] The only constant identity that runs through my life as a thread is ‘dancer.’ This is more important to me than gender, name or any other identifying features. even more important than mother. I wouldn’t admit that in the NT world as when I have, I have been corrected (after all Mother is supposed to be my primary identification, right?!) but I feel that I can admit that here.

Taylor

Mine is Artist. Thank you, Taylor.

Jessie

Participants also discussed ways in which the discovery of their autistic identity had helped them to accept themselves. Sally wrote:

‘I don’t want to be male. Yet I don’t share the female interests most women have. I don’t fit either. I wish there was a neutral.

Sally

These accounts, although very different, conveyed a common experience of individuals finding themselves unable to identify with the typical gender expectations within their environments, and their individual struggles to make sense of themselves against these.

Participants in this study provided powerful narratives describing feelings of alienation provoked by the pressure to conform to ‘‘gender-typical’’ and ‘‘neurotypical’’ expectations of them. Gender identity is traditionally perceived in terms of binary categories, which is not useful for those who do not conform to them.

The connection between participants’ interests and gender identity was an important and unexpected finding of this research. Participants’ questioning of their gender identity often stemmed from their interests not conforming to those typically associated with femininity.

Participants in this study provided powerful narratives describing feelings of alienation provoked by the pressure to conform to ‘‘gender-typical’’ and ‘‘neurotypical’’ expectations of them. Gender identity is traditionally perceived in terms of binary categories, which is not useful for those who do not conform to them.

“I Don’t Feel Like a Gender, I Feel Like Myself”: Autistic Individuals Raised as Girls Exploring Gender Identity

Autistic women and nonbinary people have sometimes struggled with how society tells them they’re supposed to act. Some autistic women felt pressured to adopt traditional gender roles (and the burdens that come with them), such as wife, mother, and girlfriend, finding “this incompatible with how they wanted to live.”

We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

Call me a girl again Not asking for the hell of it Call me a girl again My gender's not your business Call me a girl again Not asking for the hell of it Call me a girl again Non-binary resistance! (Woah-oh) They them, they them! (Woah-oh) They them, they them! (Woah-oh) Not asking for a friend (Woah-oh) They them, they them! (Woah-oh) They them, they them! (Woah-oh) Not asking for a friend --They/Them by Dream Nails

If gender is a social construct, then autistic people, who are less aware of social norms, are less likely to develop a typical gender identity. Autistic girls may not envisage themselves becoming wives and mothers when they grow up. If social constructs are made of symbols and representations, then autistic concreteness may lead to a less generalized, and more personal gender identity. Therefore, autism may redefine womanhood in a unique way.

Women from another planet? Feminism and AC awareness

Main Takeaways

- Due both to their ability to denaturalize social norms and to their neurological differences, autistic individuals can offer novel insights into gender as a social process.

- Examining gender from an autistic perspective highlights some elements as socially constructed that may otherwise seem natural and supports an understanding of gender as fluid and multidimensional.

- Confronting and denaturalizing social norms describes the terrain of many autistic lives. We’re social construct canaries.

- Copia provides a strategy of invention, a rhetorical term for the process of generating ideas.

- Autistic people are recognising and preaching the fluidity and/or flexibility of things like sexuality, gender, time, love, career and more.

- Gender identity is how we make sense of our gender subjectivity, the totality of our gendered experiences of ourselves.

- People construct gender identity from an endless list of more ‘basic’ building blocks.

- To arrive at a gender identity, we arrange gender subjectivity like building materials.

- Accounts of gender identity that would be stereotyping or bioessentialist if universalized remain acceptable at the individual level.

- Psychological synthesis of gender subjectivity into gender identity is particular to the individual.

- Gendered experiences are not static.

- While gendered experiences often demonstrate stability over time, there is no unbreakable promise against change.

- Gendered experiences may also vary situationally, relationally, or temporally.

- I don’t ‘feel’ like a gender, I feel like myself.

- Interests play a role in defining both gender identity and identity in general.

- My sense of identity is fluid, just as my sense of gender is fluid.

- Autistic individuals have described feeling pressure to ‘‘mask’’ their autism. They often do that by “performing” normative gender roles.

- “Doing” gender as socially expected can be incredibly draining for autistic individuals.

- Discovering their autistic identity might help autistic individuals process their gender identity as well.

- The connection between participants’ interests and gender identity was an important and unexpected finding of this research. Participants’ questioning of their gender identity often stemmed from their interests not conforming to those typically associated with femininity.

- Autistic people describe feelings of alienation provoked by the pressure to conform to ‘‘gender-typical’’ and ‘‘neurotypical’’ expectations of them.

- Gender identity is traditionally perceived in terms of binary categories, which is not useful for those who do not conform to them.

- If gender is a social construct, then autistic people, who are less aware of social norms, are less likely to develop a typical gender identity.

- If social constructs are made of symbols and representations, then autistic concreteness may lead to a less generalized, and more personal gender identity. Therefore, autism may redefine womanhood in a unique way.

Why don’t you study my gender? Tell me it’s not enough Shout at me in the streets Claim it’ll make me tough Why don’t you study my gender? Tell me there’s only two Tell me that it's perfect It's enough for me and you Why don’t you study my gender? Peddle those tired old lines That the violence is justified 'Cause it saves the right kind of lives Why don’t you study my gender? Tell me I’m no fun anymore That I used to bе quiet and pretty And you liked thе old me more Why don’t you study my gender? Stretch it out so we both can see Ask invasive questions Pretend you’re not hurting me Because when you study my gender And we fight this dirty war And I tell you that you’re trash And you call me a whore We’ve nothing gained and Nothing ventured and there’s No outcome we haven’t seen before So go ahead, study my gender Bring all your fears and insecurities To the fore 'Cause when you study my gender Guess what I like the new me more 'Cause when you study my gender Guess what I like the new me more

Gender and Minority Stress

The story continues with “Gender and Minority Stress“.