Therein lies our triple empathy problem (Figure 2). Patients struggle to see their doctor’s perspective, and doctors can also struggle to see their patients’ perspectives. For example, when doctors are patients themselves, they experience healthcare with their own medical knowledge. The difficulty is seeing the perspective of a patient without any medical knowledge. Similarly, autistic people struggle to see non-autistic people’s perspectives and vice versa. So, it proves even harder for autistic patients to see their (non-autistic) doctor’s perspective, and even harder for (non-autistic) doctors to see autistic patients’ perspectives. This extension of, and addition to, the double empathy problem is further supported by our finding that respondents with healthcare backgrounds did not report better experiences within healthcare access.

Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study – Sebastian CK Shaw, Laura Carravallah, Mona Johnson, Jane O’Sullivan, Nicholas Chown, Stuart Neilson, Mary Doherty, 2023

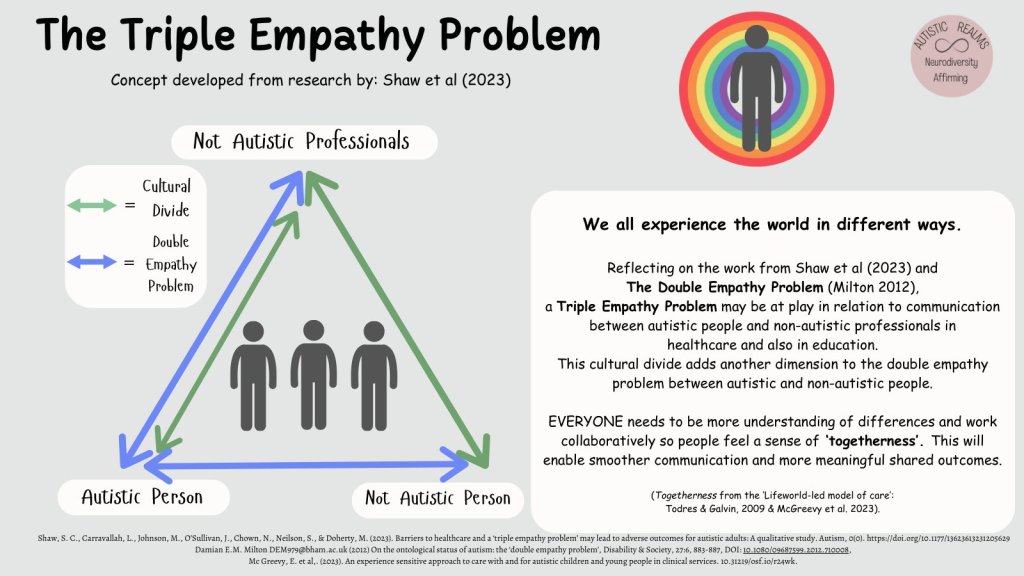

The “triple empathy problem” acknowledges the friction of communicating between semiotic domains. It brings the difficulty of communicating between domains into the double empathy problem and notes the epistemic injustice of it all.

This triple empathy problem may also be at play when autistic people interact with other professions and services, such as education, social care or the justice system.

Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study – Sebastian CK Shaw, Laura Carravallah, Mona Johnson, Jane O’Sullivan, Nicholas Chown, Stuart Neilson, Mary Doherty, 2023

During our analysis, it became clear that there was a perceived mismatch in communication, understanding, agendas and empathy between respondents and their doctors, which appeared more complicated than, and not fully explained by, the double empathy problem. Many of our respondents referred to matters that demonstrated bi-directional difficulties between themselves and their doctors – some of which we explored within Theme 2 (‘communication mismatch’). Autistic people are potentially less likely to infer the meaning of unspoken messages from non-autistic doctors. For example, concern on the part of doctors may often be conveyed non-verbally, so this message may be missed or misinterpreted as nonchalance or even contempt. However, this two-way mismatch did not feel fully representative of the social phenomenon we were witnessing within our data. As such, in relation to healthcare access for autistic adults, we propose that a triple empathy problem was at play.

Considering healthcare delivery more widely, it is common for bi-directional communication difficulties to exist between doctors and patients. It is well known that mismatched communication, understanding and agendas within medical consultations, alongside poor doctor–patient relationships, form barriers to clinical care for all patients, whether autistic or not – leading to reduced standards of care and worse clinical outcomes in the short term (Hinchey & Jackson, 2011; Mamede et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). This likely stems from the fact that medicine has its own culture, language and practices. Those working within medicine are trained in and spend years experientially learning to join and embody this culture, which would naturally be alien to those external to it. For example, the primary role of a GP is often to rule out serious causes for symptoms, and then to explore common ones (Foot et al., 2010). Similarly, from an insider perspective on medicine, it is all too common for symptoms to go unexplained beyond this, even following investigation from specialist services. From a non-medical perspective, however, the concept of medically unexplained symptoms, or the lack of explanation, can be highly distressing (Kirmayer et al., 2004). This can foster tension between GPs and patients in such contexts, be they autistic or not.

The cumulative toll of these cultural and agenda differences, which occur between all patients and their doctors, concurrent to the double empathy problem, seemed to have a particularly strong impact on healthcare experiences and perceived outcomes for our autistic respondents. When autistic respondents described interactions with non-autistic healthcare providers (undoubtedly the majority), this dynamic took on a three-dimensional quality. Therein lies our triple empathy problem (Figure 2). Patients struggle to see their doctor’s perspective, and doctors can also struggle to see their patients’ perspectives. For example, when doctors are patients themselves, they experience healthcare with their own medical knowledge. The difficulty is seeing the perspective of a patient without any medical knowledge. Similarly, autistic people struggle to see non-autistic people’s perspectives and vice versa. So, it proves even harder for autistic patients to see their (non-autistic) doctor’s perspective, and even harder for (non-autistic) doctors to see autistic patients’ perspectives. This extension of, and addition to, the double empathy problem is further supported by our finding that respondents with healthcare backgrounds did not report better experiences within healthcare access.

Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study – Sebastian CK Shaw, Laura Carravallah, Mona Johnson, Jane O’Sullivan, Nicholas Chown, Stuart Neilson, Mary Doherty, 2023

The recruitment of autistic physicians and healthcare professionals could ultimately help to overcome the triple empathy problem that we have described, through the intuitive understanding that comes from their dual insider positioning within the autistic population and within the healthcare system.

Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study – Sebastian CK Shaw, Laura Carravallah, Mona Johnson, Jane O’Sullivan, Nicholas Chown, Stuart Neilson, Mary Doherty, 2023

Due to prevailing stereotypes and a historical tradition of deficit-focused approaches to screening and diagnosis, the majority of autistic adults are indeed likely to be undiagnosed, particularly those without co-occurring intellectual disability (Brugha et al., 2011). Such stereotypes may be perpetuated through an epistemic injustice, whereby autistic people may not be seen as credible sources of information in the evolving understanding of autism in medical contexts. Epistemic injustice can be defined as ‘harms that relate specifically to our status as epistemic agents, whereby our status as knowers, interpreters, and providers of information, is unduly diminished or stifled in a way that undermines the agent’s agency and dignity’ (Chapman & Carel, 2022). Centring autistic voices within the evolving research discourse around autistic healthcare may, therefore, be key to producing an ethically sound evidence base that advances social justice and health equity for autistic people (Kidd et al., 2023).

Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study – Sebastian CK Shaw, Laura Carravallah, Mona Johnson, Jane O’Sullivan, Nicholas Chown, Stuart Neilson, Mary Doherty, 2023

Related reading,